July 1992

Swan song – now it’s over to you

In the final article of his Masterclass series, Ian Wallace poses some important questions for British birdwatchers. Are we doing enough for the younger generation? Do birdwatchers know enough about themselves? And finally, why aren’t we doing more for birds in peril?

WHEN I took a turn on the Bird Watching stand at last August’s British Birdwatching Fair, I found Dave Cromack in sombre mood over the current fortunes and roles of local birdwatching groups or societies. He was particularly doubtful that these bodies were maintaining their traditional production of skilled observers. It seemed that they were competing less effectively than before for the allegiance of the young birdwatcher.

From my contacts with the RSPB I know, even as an energetic, educative organisation, it had real problems in retaining YOC members past their early teens. Dave and I agreed the modern function of the local birdwatching society could do with investigation and later discussion in this series.

Remembering how well Bird Watching’s county and area reporters had answered a questionnaire on birdwatching in the 1980s, another was prepared. It took as its subject the role of the local group or society in birdwatching and we hoped for many comments.

Of the 110 or so current reporters, only eight answered! This was less than one in five of the number who responded in 1990 and, for Dave and me, a miserable showing. Has it left what had seemed important questions begging?

We debated giving up the task but, in the end, decided the issues should at least be aired. So, I went back to the 1990 data, read again the 36 letters which came in hot pursuit of my then recent critiques of twitching and looked for clear streams of opinion.

The starting position was that the still-growing phenomenon of twitching, now visibly abetted by competitive birdlines, was the antithesis of true or better, perhaps, studious, local birdwatching. On balance, the letters from individuals either speaking for themselves or on behalf of their societies denied this statement.

Twitching was considered neither a damaging nor a permanent behaviour pattern and mature observers involved with regular historical or scientific recording saw it as an occasional, harmless bonus.

Conversely, a few correspondents – tellingly all of them young – expressed real concern at the attitudes twitching was promoting in their peers and themselves. They were clearly finding it difficult to develop broad ornithological skills. Some older correspondents coupled this with an increased selfishness in the general behaviour of birdwatchers.

Given the mere eight completed questionnaires to the latest survey, it is difficult to develop these observations but certainly the answers contained further evidence that young observers are not using the services of local groups and societies as my generation did.

There was also real concern with such bodies that twitchers, particularly young ones, were paying through the nose for what they got.

By re-analysing the questionnaires, I was able to construct a 500 person sample of local group or society membership. From this, some further clues appeared.

• In the sample, group or society allegiance was highest at age 51-60, falling through 60+, 41-50, 31-40 to 21-30 and 13-20. The incidence of active field study and record contribution was highest at age 41-50, falling through 51-60, 31-40, 21-30 to 60+.

• A combined score of allegiance and contribution (= ‘usefulness’) produced the same variance as the incidence of field study. It suggested that in local groups and societies, 41-50 year old birdwatchers are twice as ‘useful’ as any other age class and five times as productive as 21-30 year olds!

• It follows that in the sample the most scientifically-minded (and social) birdwatchers were fledged in the 1940s and 1950s. Their productivity in ornithological terms was most obvious in regular attendance at meetings or lectures and detailed record submission

(50-55 per cent in both cases); participation in national surveys (37 per cent) and in local studies (34 per cent); and occasional attendance at field meetings (20-25 per cent).

• The personal attitudes of the mature members to new ones could not be deduced from the 500 sample but three of the eight correspondents admitted the latter were not well treated. In seven cases, young people were only briefly welcomed or left to their own devices until they had gained acceptance.

• No attempt to vary apprenticeship according to early expressed interests was noted, and in three groups, there was an acknowledged absence of young observer training. Small wonder then that in seven of the eight groups and societies, the average age of members was rising, with more members in the 41-50 group than in any other.

• Asked what the main external influence on local groups and societies was, seven of the eight correspondents were unanimous in selecting the modern ornithological media, particularly the monthly journals and the birdlines. It also thought these were indeed having a negative effect on the local fabric of birdwatching.

• The negative effects were specified as selfishness, lack of basic skills, obsession with rarities, too much expenditure on the last and other ‘non-productive’ subjects and loss of written records.

So, in contrast to the soothing letters, I conclude there is more evidence that birdwatching is in a period of considerable change and disturbance. Significantly perhaps, four of the eight correspondents reported their groups or societies were resorting to advertising in order to attract members who would continue their tradition of report publication and co-operation with national organisations such as the BTO and RSPB.

With annual subscriptions in the eight cases no higher than £11 [early 1990s prices], the price of their menu of meetings, regular bulletins, annual report, skill training (after beginning) and libraries was certainly not high.

From this point, the trail of became difficult to follow. In my opinion, their members’ increasing age has to be the most alarming finding. The past crucibles of amateur ornithology may indeed be losing their influence on young observers. Who then speaks to them?

The answer is not clear, although it is certain the Young Omithologists’ Club of the RSPB does a fine job with about 100,000 – to the point of causing some local groups to worry about the usurping of their role.

Their next stops or call stations would appear to be Bird Watching magazine, the birdlines and the persistent peer, often more localised grapevines. Most of the last have links to local groups and societies but the level of commitment to those bodies remains very unclear.

It has been suggested that Bird Watching magazine could do more to assist local groups and societies. Interestingly, the completed questionnaires contained requests for a series on club or society histories and achievements, the wider publication of the county recorders’ list, a calendar of club diary dates and full-blown sponsorship. I wonder if the general readership would welcome such changes to their magazine.

For the moment, the only obvious new initiative in support of local birdwatching efforts is the new BTO – bird clubs partnership. The move to the Nunnery appears to have rejuvenated the BTO and this year a refreshing stream of new-look BTO News, press releases and ‘first-time’ regional newsletters has done much to invigorate my ornithological mail.

It also provides clear evidence the combined efforts of professionals and amateurs are being directed to more and more specific studies. My Staffordshire newsletter contains news of no less than 11 projects, including the 1992 Pilot Census which will hopefully provide more complete and more representative coverage of our country’s birds than the BTO’s Common Birds Census.

It is also timely. It is difficult to watch birds within the astonishing intensity of modern farming technology, as I do, and not fear for all their futures. Puzzled farmers ask me where the birds have gone.

I simply point to the almost aseptic monocultures they themselves create and the increasing dearth of stubbles and even brown land. “Needs must”, they say, but I sense they are concerned, a few even shameful.

It has to be one of our major priorities, perhaps the most important of all, to find a new accommodation between modern agriculture and a continuing diversity of birds.

To this end, we need a commitment from not just middle-aged observers but young ones. They are needed to carry the batons of amateur field ornithology forward.

So, we are back once again to the need to fledge a new generation of ‘trained soldiers’ (= the reversal of the ageing of ‘useful’ observers). The optimists who wrote to me claim these precious people will arise spontaneously from the relatively enormous numbers of us who are more or less interested in birds. The pessimists (and I must make it clear that I am near being one) will still wonder how and where the necessary broad knowledge and study skills will be acquired.

Accordingly, there is a need for increased responsibility to be accepted by amateurs, and yet this must not reduce what remains a hobby to most of us to something like work. It is a considerable challenge and it will not be met if the trend to increased selfishness continues.

I have to admit I feel much dismay at the conduct of birdwatchers en masse. But then, at 58, I am no longer in the mainstream. Nostalgia may be obscuring my perceptions. So, who shall tell us how we really should feel about birds and their causes?

The increasingly significant ownership or management of scarce habitats by the RSPB is a marvellous achievement but does the society really speak for all of us or address the whole of natural history enough?

Digging deeper to benefit birds

Nobody enjoys late May and October more than I do. My eyes are constantly on the weather maps and I bless the fates when my holidays are full of migrants and vagrants. We are extraordinarily fortunate in these islands to receive regular deposits of North American and particularly Asian birds, and I blame no-one for chasing after them.

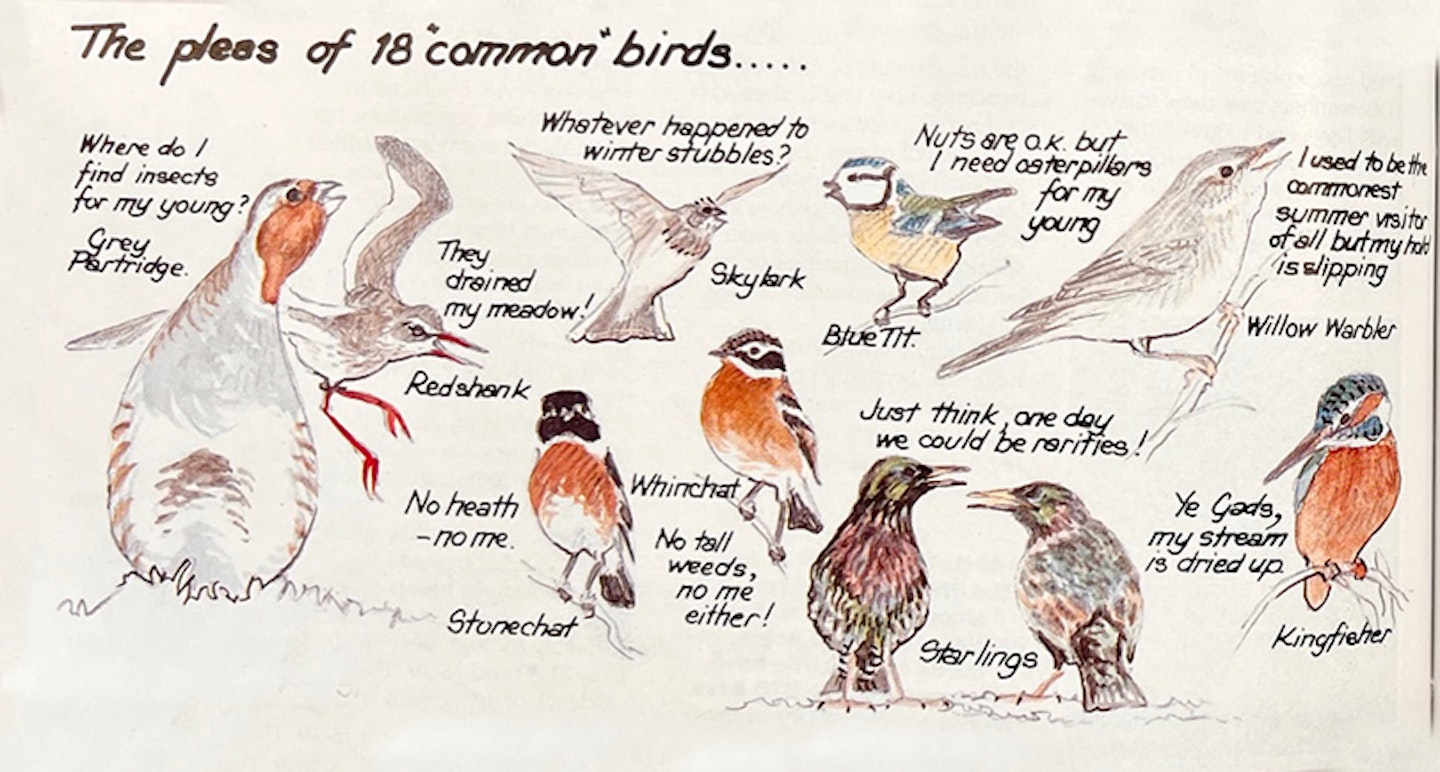

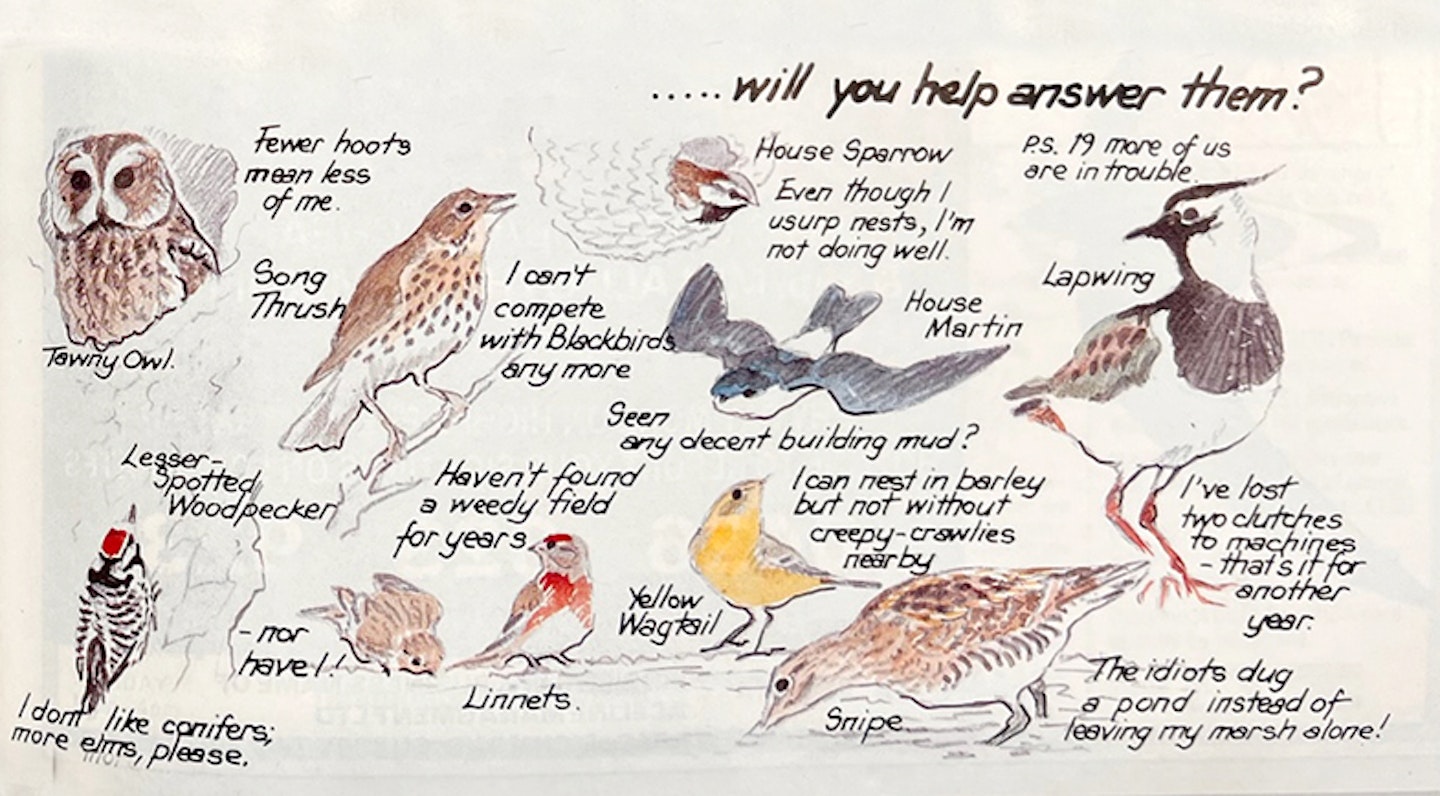

I have tried in Masterclass to stress the benefits of local study. In the end much more sustaining than any other kind of observation, it can nevertheless present some uncomfortable visions, nowadays. As current BTO studies show, at least 30, maybe 40 common species are in natural or local decline. We need to know why.

Then with research and a fuller dialogue with landowners and farmers, we might turn what threatens to be a widespread disaster into a famous example of broadly-applied conservation.

If we want the beauty of breeding Lapwings in ordinary farmland, we need brown land in spring – not six thick inches of autumn-sewn barley – but this year there are only three such fields along my count lines. Accordingly, I have 5.5 pairs where last year I had at least 15 and those which laid early lost all their eggs to a heavy roller. Three are back on new nests but all I can do is pray!

Among the other delightful, once thought eternal, species at risk in our seemingly still pretty countryside are Grey Partridge, Tawny Owl, Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Skylark, Meadow Pipit, Song Thrush, Tree Sparrow, Linnet and Corn Bunting. I look at this short list, think back to the 1940s and feel nothing but sad.

Add to the above the summer visitors which are also in trouble and the list extends to include

Turtle Dove, Whinchat and Spotted Flycatcher. I feel sad and desperate.

One of the wisest conservationists I know is

Malcolm Ogilvie, with many years with wild geese behind him and currently with the care of Islay’s marvellous avifauna as his main task

*I worry about the future of birdwatching,” he once said, “we just don’t pay enough or work hard enough for our pleasures” Knowing how much I valued the freedom of the chase in my early decades, I was not sure I agreed with him – but I do now.

Are we really going to go on inviting young observers to spend hundreds of thousands of pounds on identification books, rarity news and fossil fuel? If, as I fear, we are, we may well rue the day we started to distort a marvellous hobby and began to sell our own ‘common’ birds short

Here endeth Masterclass!

Ed [David Cromack, 1992]: Ian has thrown down the gauntlet, but who will come up with the vibrant new ideas to broaden skills and involvement in ordinary old-fashioned birdwatching? Whether you are a hard-pressed club officer, newcomer anxious for more help or a dedicated BTO volunteer, we would like to hear from you. Please write to help foster debate on this vital topic