March 1992

Status Quo!

Status, in human terms, means rank or social station. In the bird world it means the state of a species in a particular place and time. Ian Wallace looks at the question and how it applies to two of our commonest birds.

After a period of name collection, it is normal for observers to try to make more of their sightings. Hence the long British and Irish tradition of sending records to the editors of local, county and, increasingly, national bird reports.

The most useful product of these, usually annual, publications has been the increasing definition of avian fortunes brought, if not yet to a fine art, at least to a remarkably sustained effort, by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and the other conservation bodies.

Witness the two marvellous atlases of breeding and wintering birds and the excellent collation of studies recently published in the NCC/BTO’s conservation and monitoring review. Entitled Britain’s Birds in 1989-90, the last is a treasure trove of facts and future directions in species research and protection.

It made sense to me therefore that I should convey to you the ways in which your own records can add further to the definition of avian status, whether of individual species, tribe, family or all birds.

Accordingly, I looked out my classic tomes – the Handbook, the Dictionary and the British Ornithologists’ Union’s Status of Birds in Britain and Ireland – and searched for an ornithological definition of ‘status’.

To my surprise, I found that all these books presumed a prior understanding of the word and concept. I scurried back to Collins.

There I found that the word was first used in the 17th Century, stems from the Latin verb stare (to stand) and has radiated through its early meaning of posture to become five direct or indirect variants of that word. In scientific terms, only two of these appeared relevant – “the relative position or standing of a person or thing” and “a state of affairs”

Looking further into the BOU’s book, the notes indicated that status was

effectively the compound of systematics, categorisation, distribution and relative abundance.

It follows that we need to assess several states or measures before we get to an overall view of status. Let us begin with categorisation.

Adopted first in 1970, four classes are used by the keepers of the British and Irish list [Note these categories have changed in recent years, and there is no longer a Category D]. In brief, these are:

A – apparently wild, seen at least once in last 50 years

B – apparently wild, seen at least once but not in last 50 years

C – originally introduced but now breeding in the wild and regularly without assistance

D – recorded in last 50 years but (i) not qualifying for A because not apparently wild or undoubtedly ship-assisted or only found dead on tide-line and (in) not qualifying for C because populations not self-supporting.

The four-tiered categories give our national list a dynamic quality which has stood nearly all tests for over two decades.

Next comes the classification of behaviour and particularly residence (or lack of such). This has always to be related to an area with clear boundaries but virtually of any size.

Once again the BOU has set a discipline on behaviour and residence (or better perhaps degrees of such events). There are eight.

1 RB (resident breeder);

2 MB (migrant breeder);

3 IB (introduced breeder);

4 CB (casual breeder);

5 FB (former breeder);

6 WV (winter visitor);

7 PV (passage visitor);

8 SC (scarce visitor)

Most of you who read widely about birds will know that other terms are used. Indeed the vocabulary is rather loose. So it is important to recognise, for example, that MB contains all breeding “summer visitors”. PV are more usually called “passage migrants” and even “transients” and SV includes all “vagrants”“ and nearly all “rarities”

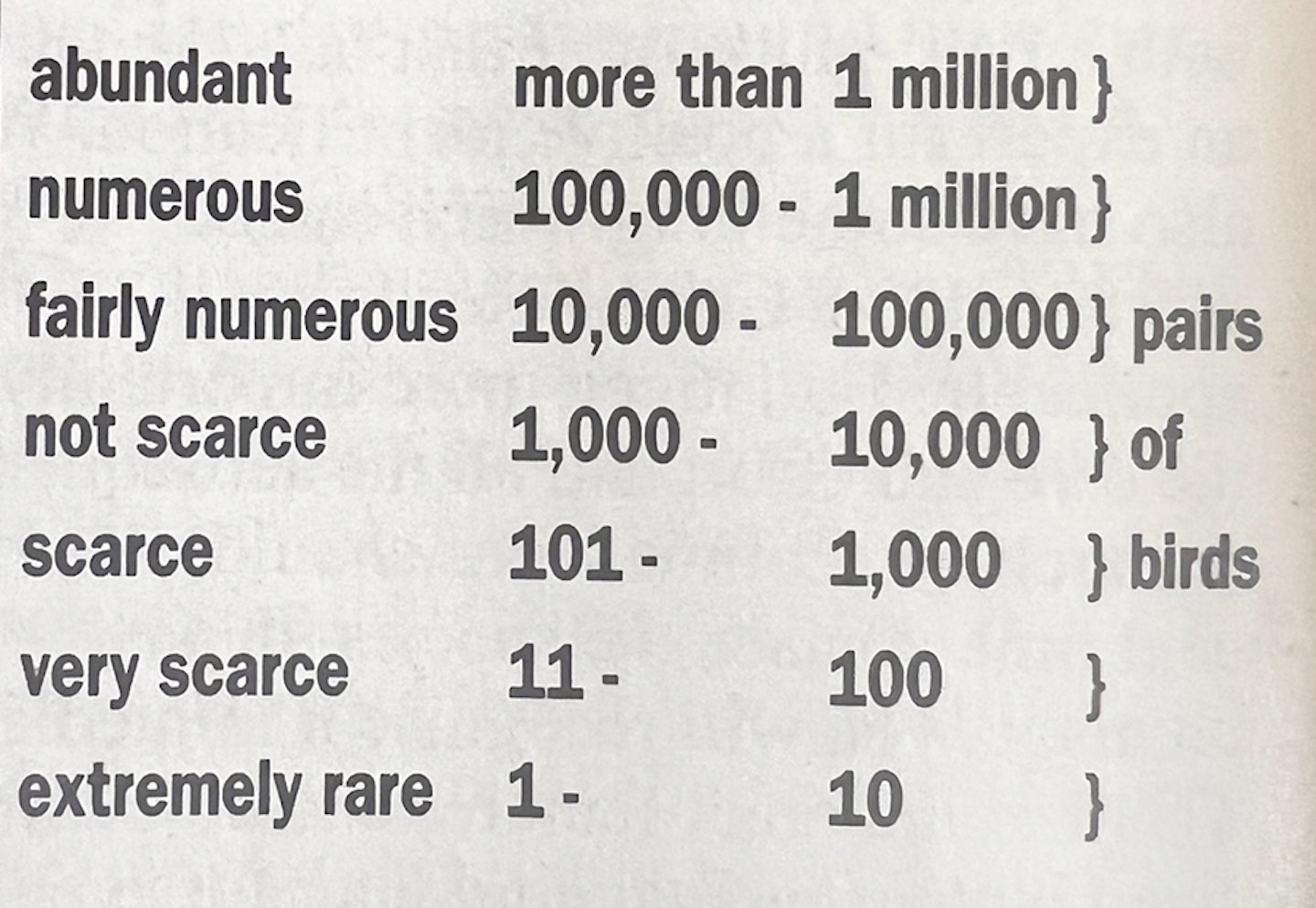

In measuring relative abundance on a national scale, the BOU dealt only with breeding birds (in the B classes) but fixed the following measures for Britain and Ireland together :

Unlike the other qualifications of status, this does not sit well in smaller areas and many regions, counties, and localities have adopted differing, more relevant scales.

Given a bird’s specific or-subspecific identity and the above classes, the overall status of any one can be defined. Accordingly, in 1970 our national bird, the Robin, was awarded the following state of affairs (my precis):

RB; also MB; abundant; widely distributed, (breeding nearly everywhere except Shetland; breeding race melophilus (essentially resident but some SE birds move to Iberia); PV; migrant race nominate rubecula occurring March to May and conspicuously September to November, particularly E and S coasts; most moving on S; origins include Finland, destinations as far as Algeria; WV (again rubecula, unqualified).

From other information available in 1970, the scale of passage could have set up to 1,000 or more birds in localised falls but no-one then, or since, has estimated the numbers of winter immigrants.

By now, I hope that any thoughts of the Robin as merely a charming, tame garden bird have been disrupted. It is in fact a remarkably dynamic chat.

What has the last 23 years told us of Robin status? Firstly, the combined findings of the Common Bird Census and the breeding atlas produced in 1968-72 a full estimate of the breeding population – about five million pairs.

Over the following 20 years, Robins became less common, particularly on farmland, and by the time of the wintering atlas in 1981-4, the breeding community was set more reasonably at 3.5 million pairs, with the December population separately estimated to be more than 10 million birds – five to ten per cent of the European population.

Interestingly, the wintering atlas showed, too, that Robins shifted in winter, withdrawing from higher altitudes and filling up the northern and north-western isles where they do not breed. The latter occupation stems probably from immigrations from north-west Europe.

A close reading of the massive Robin literature – few birds have been so studied – adds other amendments to its status. Only the males of our subspecies are truly resident; their mates move at least locally to defend separate winter territories. Thus the bold cock Robin that ate your Christmas scraps could actually have been a wandering spouse!

The latest news of our native Robins is mixed. It was good in the summer of 1989, with rises in both the farmland and woodland indices of the BTO’s Common Birds Census. But the odds must be that increased mortality in the 1990-1 winter and the miserable 1991 spring will have led to a decline.

Certainly, my local birds are at a low ebb, even in sheltered coverts. Even so, the BTO regards it as an essentially stable species, with each adult pair successfully rearing two chicks to independence each year.

"I believe that when or where there are gaps in the occupation of habitat by British Robins, the odd foreigners will occasionally settle down"

But, what about the Robin as passage migrant and winter visitor? The answer here is decidedly tougher. It looks certain, however, that although it is still a regular migrant it has, along with the Redstart, become much less numerous. The 1,000-bird falls of September and October appear to belong to the past. Its status in Europe may well have changed.

‘Why?’ is a considerable question.

As a true winter visitor to our mainland – taking up temporary residence – the nominate European race is, to my eyes, rare. My two most recent study areas have presented a few greyish-backed and orange-breasted birds quite regularly in October and November, but they either move on quickly or hide. The latter behaviour is quite likely as it is only our race that is confiding.

In the last 13 winters, I have seen less then ten, so-called, continental birds in winter. One at Everingham held territory in dense birch swamp (had it been bred in white taiga?). It was a superb songster but hid at the slightest disturbance. Another near my current home was in a sallow marsh as late as April 21. So I believe that when or where there are gaps in the occupation of habitat by Britishers, the odd foreigners will occasionally settle down.

Also, is the Robin a scarce visitor or rarity? Well, no-one has proved the point beyond all doubt but, as I related in an earlier article on subspecies, a few East Coast observers do see and have trapped a handful of birds that resemble the even paler, most eastern race tataricus. It would be no great shakes for a Robin to come from Russia. Every last Pallas’ Warbler does more!

So, for my money, the current status of the Robin is even more dynamic than our textbooks suggest.

It could be as follows:

Erithacus rubecula melophilus: RB/MB; abundant (3.5 million breeding pairs; 10 million birds in December); males sedentary, females moving locally; SE birds may migrate SW;

WV (probably not scarce – hundreds, perhaps thousands, desert high tops; some occupy island habitats, others fill in gaps in lowlands).

E. r. rubecula: PV (fairly numerous – more than 10,000 migrants in autumn but recently decreased; mainly on E and S coasts, some moving inland; much less marked passage in E. r. tataricus: SV (extremely rare – fewer than 10 birds, within passages of rubecula.)

If all the above is true, then our national bird is not a Brit in any real sense but a highly-mobile western Eurasian. Elsewhere in its range, the status of the Robin varies with its location and habitat. Along the northern boundary of its total range, it is only MB or summer visitor. As a forest bird in the north-west African mountains and the Canary Isles, it is strictly RB and in the latter area virtually isolated. To Libya, it is just WV

Another supposedly a complex status is the Song Thrush. In 1970, the BOU allowed three races – the wholly swarthy hebridensis from the Outer Hebrides and Skye, the brown-backed and loose-spotted clarkei of the rest of Britain and Ireland and the greyish-backed and tight-spotted, nominate philomelos from Eurasia – and awarded these RB (also MB) in the first two and PV and WV in the last two.

Once again, the three populations are more dynamic than at first sight. Hebridean birds are mainly sedentary but a few have travelled to England and, once, Algeria. Mainland birds are said to be essentially resident but ringing has shown that most northern adults, nearly half of all adults and nearly two-thirds of each year’s young migrate south. Up to a quarter of the population goes overseas to France and Spain.

In my study area and others in the Midlands, Song Thrushes just “fade away” in autumn (a quote from ace ringer John McMeeking). I see only a handful or so from late autumn to mid-February when there is an obvious return of soon-singing birds.

There appears to be a massive redistribution within our lands, perhaps directed to habitats rich in snails, a food source which, unlike other thrushes, they have learnt to exploit.

Except in the “heat island” of Regent’s Park, Song Thrushes have always been the rarest thrush in my winter counts. So, I find it impossible to accept the wintering atlas estimate of six to 10 million birds, particularly in comparison to the mere one million or more awarded the Redwing. This comment takes into account the wintering of some continental birds. In my patches, they have been greater rarities than European Robins!

Since the Song Thrush is also subject to a long-term decline, with its estimated breeding population down from 3.5 to 1.5 million pairs in the 15 years to 1983, it seems to me that we may have our winter figures wrong.

There is another puzzle in the status of the Song Thrush and this is the origin (and systematic position) of the strange dark migrants that regularly fall upon the Northern Isles and East Coast at the beginning of each autumn’s winter thrush passage.

First debated 40 years ago on Fair Isle, they have no official status and yet they are not difficult to recognise, being noticeably darker above than classic philomelos but clean-spotted below like that race and quite unlike hebridensis. Are they Norwegian? We just do not know.

It is this sort of question amateur observers of my generation have long tackled. Admittedly, no new tick will come from its answer but it is just as satisfying to end a mystery. It would be good to see some of the current mass pursuit of rarities redeployed towards the many still-begging questions on avian status.

How could you play a part in the further definition of bird status? It is not easy to leap into the disciplined observations and ringing effort that the greater elucidation of Robin and Song Thrush presences or absences will require. It is not difficult however to find some easier, but just as interesting, targets.

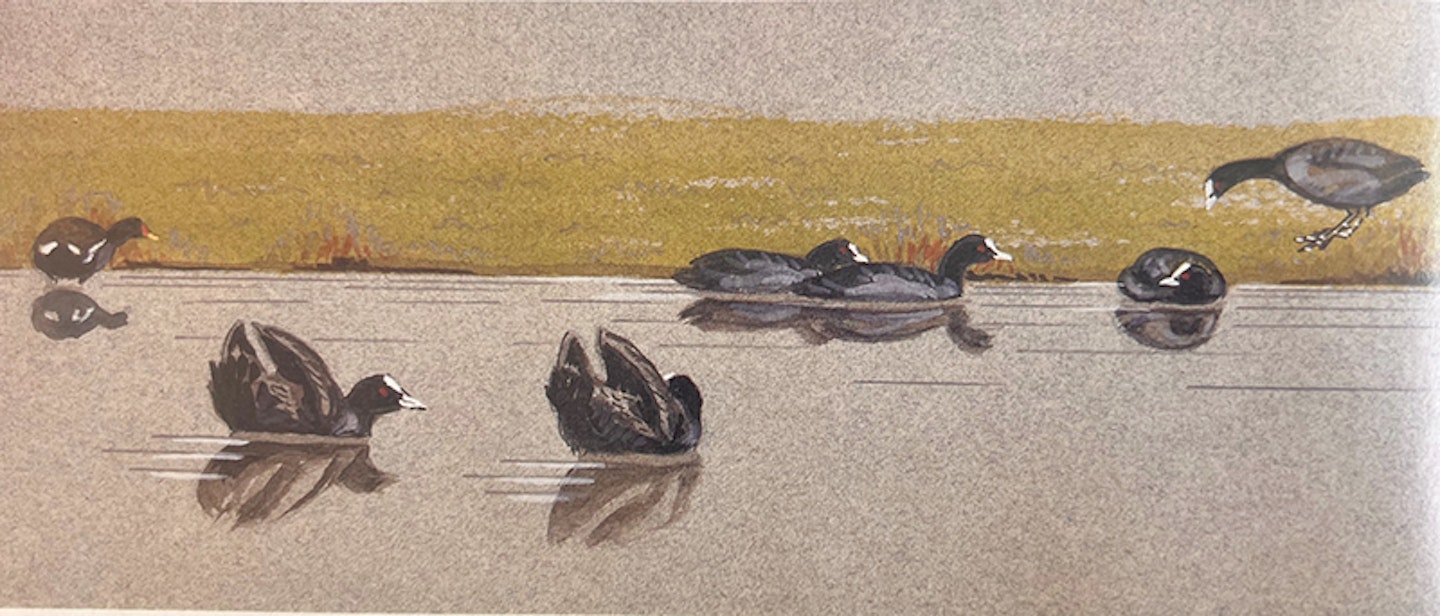

"Some of our wintering Coots come from Russia. Could you detect such influxes among local dispersals from water to grazing pasture or reservoir?"

So how about assisting the experts to understand the movements of the two common lake rails, the Moorhen and Coot? British Moorhens rarely move more than 20km from their nest sites but it could be that your resident birds are joined in winter by true migrants from Fenno-Scandia. Could you show such arrivals by regular counts at your local waters? Similarly, some of our wintering Coots come from Russia. Could you detect such influxes among local dispersals from water to grazing pasture or reservoir?

Alternatively, if you want more of an identification challenge, why not take on that teasing pair of black-capped tits, the Marsh and Willow? The current national view is that the former is 1.5 to three times as common as the latter but it is also subject to a slow decline. In my last two study areas it is the Wilow that has been more obvious, having an ability to rove in winter which the Marsh seems to lack. Could you determine the balance of their fortunes around your home?

As the occurrences of rarities become increasingly repetitive, I find the many remaining mysteries of common bird status continue to set truly fascinating challenges. Believe me, they are fun to target and explore and, what’s more, your local recorder, your county editor and even the national conservation gurus could all send you blessings if your records can contribute new clues. Do tackle some questions of status. Just asking them will make you a better birdwatcher!