October 1991

Seabirds – what’s coming next?

Birdwatching sage Ian Wallace puts aside ornithological politics and returns to birds, in a special three-part examination of species that may soon be seen for the first time in Britain. Here, in part one, he assesses a variety of seabirds, and suggests good vantage points if you want to make some discoveries for yourself.

Forecasting some potentially new British birds is a pastime that has an enduring appeal for a large number of birdwatchers, and in the early 1970s, I committed to print some of my own ideas.

I chose for my article in British Birds the passerines of high temperate Asia as my target group and listed over 40 possibilities. At least 15 of these have so far appeared. True, I missed the potential of the Two-barred Greenish Warbler – since apparently well photographed on, if not yet accepted from Scilly in October 1987 – but otherwise my bets still have the ornithological bookies worried.

In the last of these three articles, I shall revise my forecasts of Asian passerines, but here I begin with the amazing feathered wanderers of the oceans.

It took me a long time to fledge as a sea-watcher. Back in the mid-1950s when who else but the irrepressible Ian Nisbet claimed safe shearwater identifications at distances of up to a mile and a half, I merely blinked and plodded on through the suaeda bushes of Blakeney Point in search of Bluethroats. Whatever next?!

Even in the 1960s and from Scilly, I was slow to appreciate what a treasure trove of good birds the sea offered. Then (as now) sea-watching on St Agnes meant only staring south from Horse Point, and ‘a bird a minute’ was considered a good score.

Apart from one amazing passage of large shearwaters (described in Bird Watching in my ‘Those Were The Days’ series), it was all rather hard work, cold rock and incipient piles. The Irish from Cape Clear had their hands fast on the seabird blue riband of the south-west.

My attitude to sea-watching began to change in 1967. Conscripted to a sand-castling holiday in Norfolk in September, I adopted the defence mechanism of digging short and then staring long into the North Sea. The astonishing caravans of waders, gulls and terns passing offshore caught my attention and surprised the Norfolk Bird Report Editor.

In 1968, the careless loss of my St Agnes cottage slot sent me to Tresco and accidentally allowed the pleasing discovery that, compared to the St Agnes dribble, relatively huge streams of seabirds passed off the snobby island’s north end.

With Tresco’s better light (behind me) and closer birds, I broke through the ‘100 birds a minute’ barrier, and fine sights like thousands of Gannets pursued by Bonxies, a raft of Great Shearwaters and Sabine’s Gulls surf-feeding had me finally hooked as a sea-watcher. (Incidentally I suspect that the views of seabirds would be even better from the north rocks of Bryher. Alas, I have never been able to get across the chasm between them and the main island. Another new challenge for the young and nimble!)

In the New Year of 1969, my sea-watching became a lasting passion. The bosses of the Elder-Dempster Line allowed some war-weary expatriates to escape from Lagos, Nigeria, on a three day cruise to the Equator and back.

The voyage turned into a mini-Odyssey, opening up my eyes to all sorts of new possibilities in seabird occurrences. In perhaps the luckiest ever of all my birdwatching experiences, I woke up to a first foggy dawn and a ship surrounded by a mess of petrels. Among the Leach’s and Wilson’s were several Madeirans and one splendid Bulwer’s, both lifers for me.

On the second clearer day, the highlight was a distant cloud which turned miraculously into a flock of 5,000 Sooty Terns. Between these dramatic moments came others that displayed more familiar species such as Long-tailed Skuas and Black Terms. As we sweltered half way up and down the globe, the last evoked cool-sweet memories of breeding grounds two continents to the north.

Small wonder that when I returned from Nigeria, I vowed to redouble my sea-watching efforts. In 1971, I assumed that these would once again be made from Scilly but in 1972, a career lurch (back to the fishing industry) took me to Hull and the coast of the East Riding.

Propitiously, my Jack Russell ‘Sheba’ was turned off Spurn Point and so I ended up at Flamborough Head, instead. There, I soon met two local experts – the county establishment-approved Henry Bunce and Bridlington’s more rebellious Geoff Brown – and talk of seabirds soon followed. Balancing Henry’s caution (and traditional late morning arrivals) with Geoff’s lack of caution (and late evening watches) was no easy task and I was forced to conclude that Filey Brigg was the only place for seabird observation.

For this reason, I initially paid little heed to the sea off Flamborough Head.

Then, in 1973 and 1974, that dark denizen of the South Atlantic – the Sooty Shearwater – saw to it that some of us would slumber through dawn no longer. For the first time ever to human eyes, the bird that flies thousands of sea miles to reach the North Sea began to appear daily in August and September and particularly in the first two or three hours after dawn.

So, if Sooties could stream in the North Sea, what other birds would pass among them? We had discovered that cautious Henry had privately logged both Cory’s Shearwater and Black-browed Albatross, but the public answer to that question did not come until 21 August 1976.

Out of the storm that ended that year’s marvellous summer came five species of shearwater in one hour. Scarcely daring to think of what this meant, Andrew Lassey, Irene Smith and I faced for the first time a richer marine phenomenon than ever noted at Filey or Spurn. Had Cape Clear real opposition at last?

In the last 15 years, the imitation and re-doubling of sea-watching round the coasts of Britain and Ireland has been remarkable. In the first of the modern, comprehensive field guides, Peter Harrison advanced our perceptions of seabirds, hugely. He has added to his original texts and paintings another telling set of photographs in a second book and has gone on to add the ‘pelagic’ trip to the exploits of the modern sea-bird hunter.

The result has been the spawning of really keen, sharp-eyed and Kowa-enriching groups of sea-watchers on nearly all the coasts of our lands. Last September, I enjoyed the company of the Sheringham stalwarts who score over Flamborough by having better dawn light and a comfortable Victorian shelter as accommodation. The latter keeps off rain but not spray. Hence the occasional ascent of watchers to its rafters!

Having recently experienced what the 40-mile west coast of Islay presents at Frenchman’s Rocks, I feel bound to try western Ireland before my eyes fail. The new place at the south-west end of Co. Clare sounds absolutely electric. I did not know to look when I was there in 1948!

I suspect that there are other areas where seabirds must be at last occasionally concentrated waiting to be discovered. Cape Wrath, Fairadh Head, Strathy Point and Dunnet Head all look pregnant to me. Youthful expeditions to Sutherland and Caithness, please.

I hope that the above comments have done enough to spur your attention. Now to what new seabirds might occur.

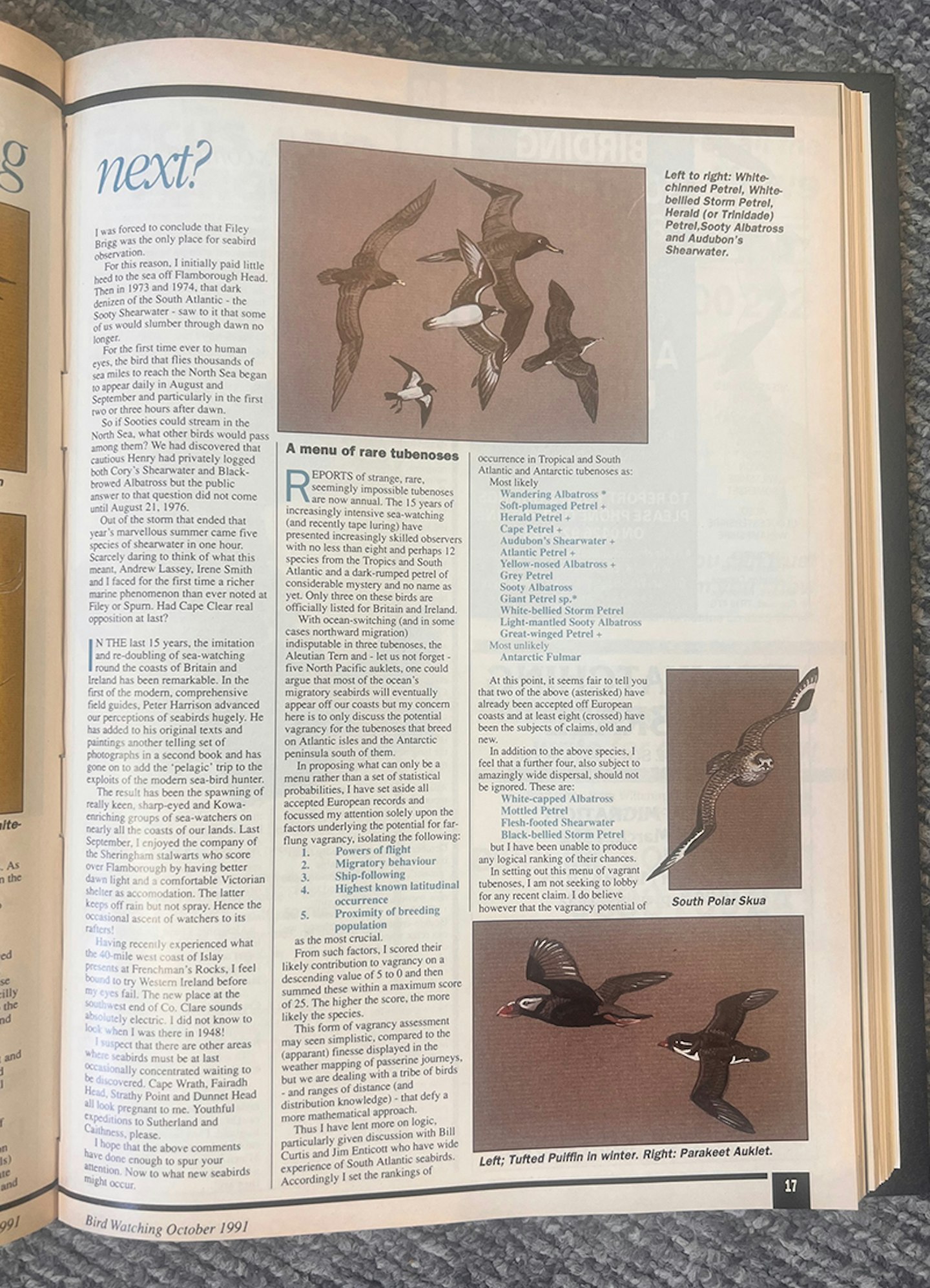

Report of strange, rare, seemingly impossible tubenoses are now annual. The 15 years of increasingly intensive sea-watching (and recently: tape luring) have presented increasingly skilled observers with no fewer than eight and perhaps 12 species from the Tropics and South Atlantic and a dark-rumped petrel of considerable mystery and no name as yet. Only three on these birds are officially listed for Britain and Ireland.

With ocean-switching (and in some cases northward migration), indisputable in three tubenoses, the Aleutian Tern and – let us not forget – five North Pacific auklets, one could argue that most of the ocean’s migratory seabirds will eventually appear off our coasts but my concern here is to only discuss the potential vagrancy for the tubenoses that breed on Atlantic isles and the Antarctic peninsula south of them.

In proposing what can only be a menu rather than a set of statistical probabilities, I have set aside all accepted European records and focused my attention solely upon the factors underlying the potential for far-flung vagrancy, isolating the following:

-

Powers of flight

-

Migratory behaviour

-

Ship-following

-

Highest known latitudinal occurrence

-

Proximity of breeding population

as the most crucial.

From such factors, I scored their likely contribution to vagrancy on a descending value of 5 to 0 and then summed these within a maximum score of 25. The higher the score, the more likely the species.

This form of vagrancy assessment may seen simplistic, compared to the (apparent) finesse displayed in the weather mapping of passerine journeys, but we are dealing with a tribe of birds – and ranges of distance (and distribution knowledge) – that defy a more mathematical approach.

Thus, I have lent more on logic, particularly given discussion with Bill Curtis and Jim Enticott who have wide experience of South Atlantic seabirds.

Accordingly I set the rankings of occurrence in Tropical and South Atlantic and Antarctic tubenoses as:

Most likely

Wandering Albatross *

Soft-plumaged Petrel +

Herald Petrel +

Cape Petrel +

Audubon’s Shearwater +

Atlantic Petrel +

Yellow-nosed Albatross +

Grey Petrel

Sooty Albatross

Giant Petrel sp.*

White-bellied Storm Petrel

Light-mantled Sooty Albatross

Great-winged Petrel +

Most unlikely:

Antarctic Fulmar

[Bold italics means a bird which has since DIMW’s predictions been accepted to British List]

At this point, it seems fair to tell you that two of the above (*) have already been accepted off European coasts and at least eight (+) have been the subjects of claims, old and new.

In addition to the above species, I feel that a further four, also subject to amazingly wide dispersal, should not be ignored. These are:

White-capped Albatross

Mottled Petrel

Flesh-footed Shearwater

Black-bellied Storm Petrel but I have been unable to produce any logical ranking of their chances.

In setting out this menu of vagrant tubenoses, I am not seeking to lobby for any recent claim. I do believe however that the vagrancy potential of tubenoses is truly phenomenal and I hope that my review of its more likely products will assist in its further definition.

A review of other vagrant sea-birds

Having studied other seabird families less than tubenoses, I feel less secure in my assessment of their chances of vagrancy.

For example. I never thought to see the central Pacific’s large Elegant Tern on the British List but logically it could be argued to be more likely than the North Pacific’s tiny Ancient Murrelet. Yet as already noted, the latter is not without historical precedents and so once again we should look far and wide.

[Bold italics means a bird which has since DIMW’s predictions been accepted to British List]

-

Patently we can ignore all penguins. None of them are going to swim up the Atlantic to replace the flightless Great Auk. We can probably ignore Western North America’s Western Grebe since, unlike the sympatric race of the Red-necked Grebe which has reached us once, it does not move east even within its continent.

-

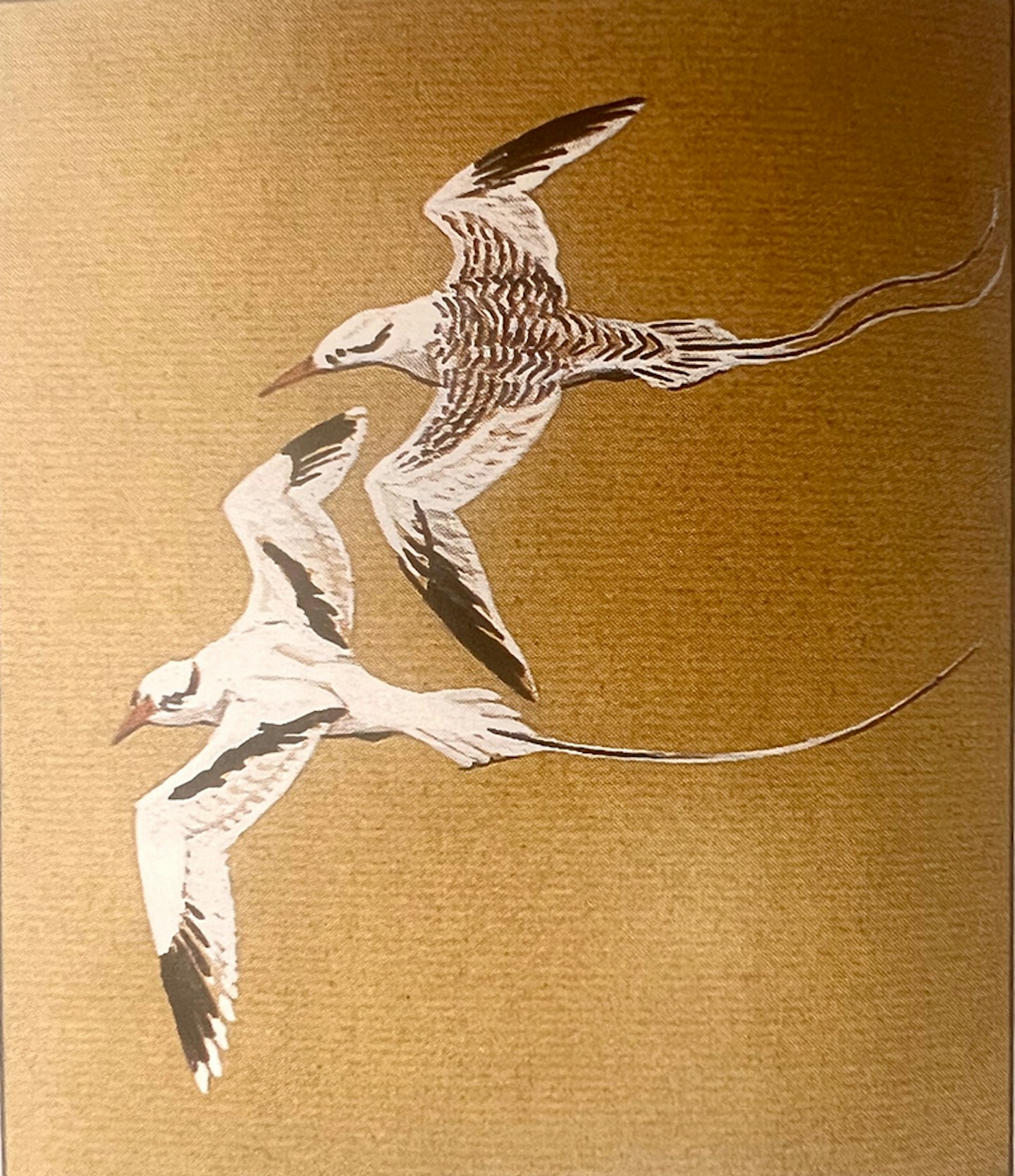

Coming to tropicbirds, we ought to pause. The Red-billed Tropicbird has been claimed from Holland and the White-tailed strays north in the Western Atlantic to the latitude of New York. Both are truly pelagic after breeding and are no more unlikely than frigatebirds.

-

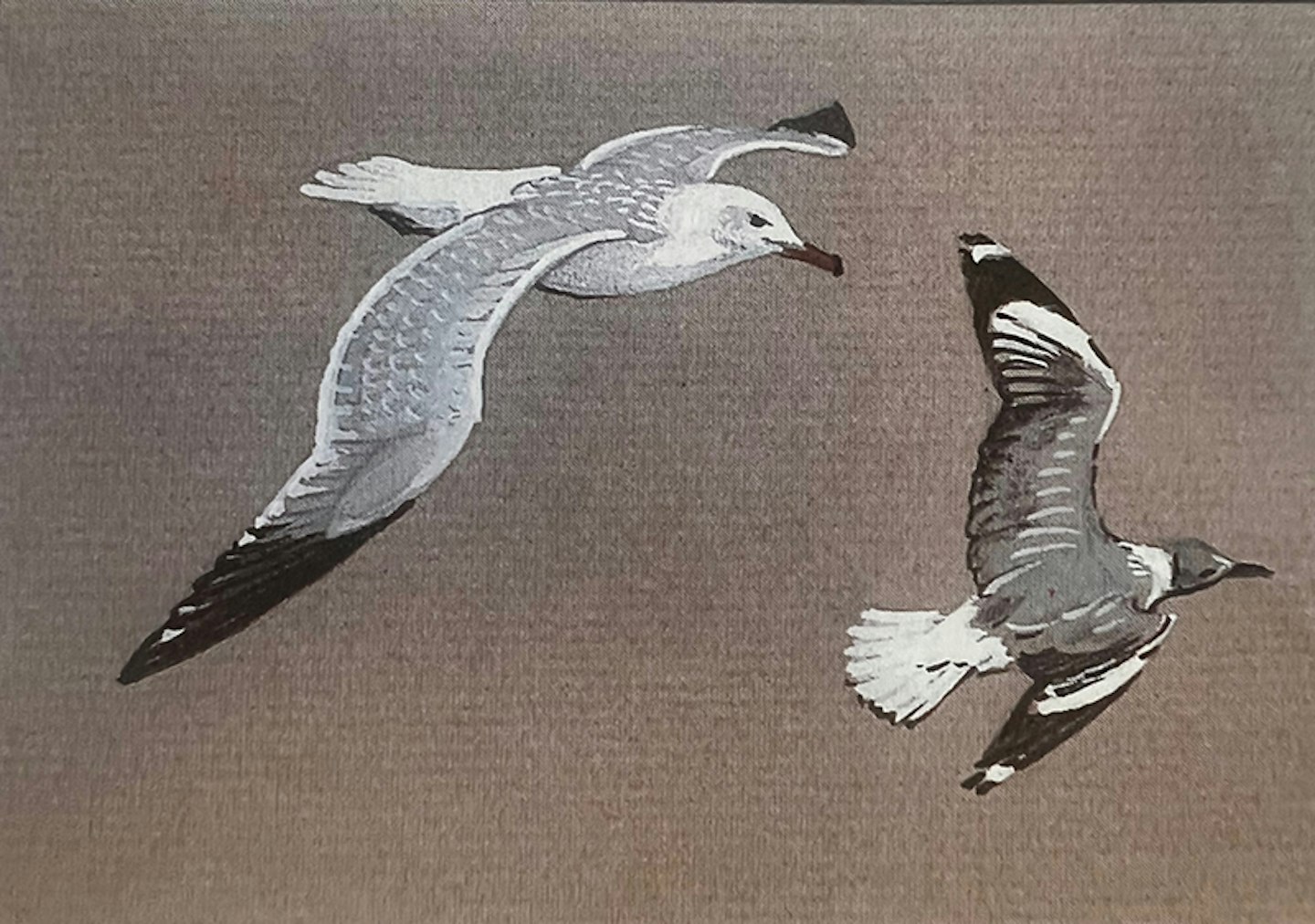

Gannets and boobies are certainly worth some study. The Cape Gannet has been claimed and the recent BB paper has me convinced that at least the Spanish reports deserve respect. The trouble is that its one truly diagnostic mark – the long black line down its throat – requires bionic eyes!

-

All three of the Central Atlantic boobies have now been reported elsewhere in Europe, the Masked Booby and Brown Booby from Spain and the Red-footed Booby from Norway. By far the worst bird that I saw last October was an undoubtedly small but otherwise indecipherable ‘Gannet’, careering over Bridlington Bay. ‘Give Gannets second looks’ now seems a sensible maxim.

-

With the full acceptance of the Double-crested safely achieved, we can relax when it comes to other cormorants and shags. No other species has the potential to reach our seas or shores.

-

Like many tubenoses, frigate birds follow ships. So we had better be aware that the Lesser, as well as the Magnificent Frigatebird, has strayed well north of the Tropics, while the Great breeds as near as Florida. [also Ascension Frigatebird]

-

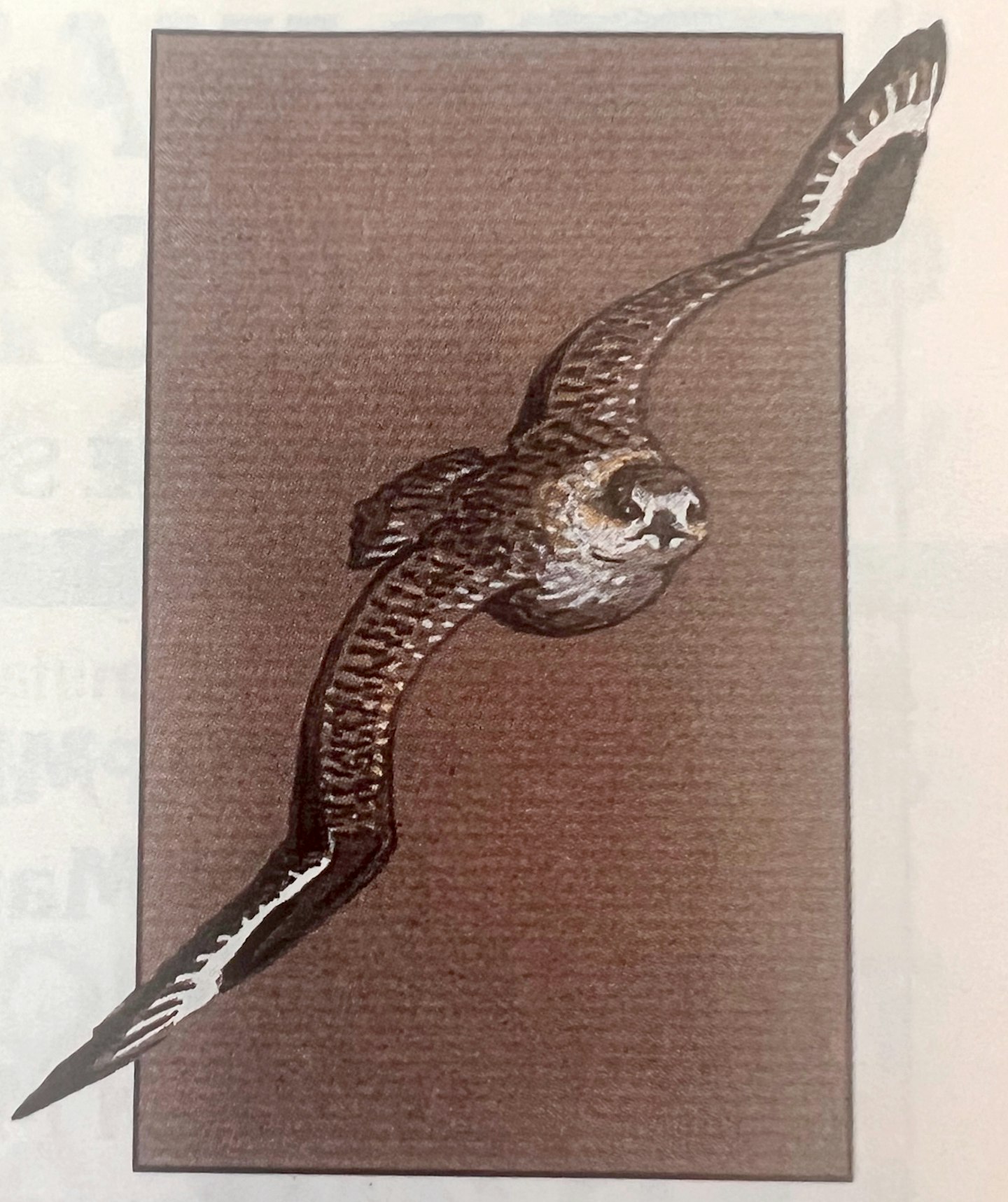

Of the three southern skuas, all closely related to our Great, none fails to show some northward vagrancy but only the South Polar Skua performs regular trans-equatorial migrations in the Pacific and less commonly in the eastern Atlantic. With a specimen taken in Greenland, it is difficult to deny it a chance to become British but clearly the similarity of some worn and bleached Bonxies is causing committee migraine. Judgements on the claims from our south-west waters are long overdue.

-

New gulls may be hard to find. The recent attempts to secure Thayer’s from the central north of Canada seem doomed. I gather that the BOU Records Committee have lumped it with Kumlien’s and Iceland. For three potential ticks, read just one, I fear. Personally I fancy Audouin’s Gull. It is doing well on its Mediterranean breeding isles and moves out into the Atlantic in autumn, reaching Portugal. I have twice had it in my sights off British coasts but sadly failed to nail it even to my own satisfaction. It is however no more unlikely than Slender-billed. Africa’s Grey-headed Gull may also surprise us. It is accepted for Iberia and crosses not only sea but also land. [also Slaty-backed Gull, Glaucous-winged Gull and Cape Gull]

-

With the recent rush of new terns onto the British List, we need to take care with the other possible species. Already we face the astonishing prospect of greeting the White-cheeked Tern from the Red Sea. Given it, the Aleutian and the Elegant, we must see this tribe as rivalling tubenoses in their vagrancy. So we should not ignore Crested and Damara from South Africa and, on a hunch inspired by a strange waif on St.Agnes one November, perhaps even the Antarctic. Finally there is the partly migratory Brown Noddy which has strayed up the eastern coast of North America.

-

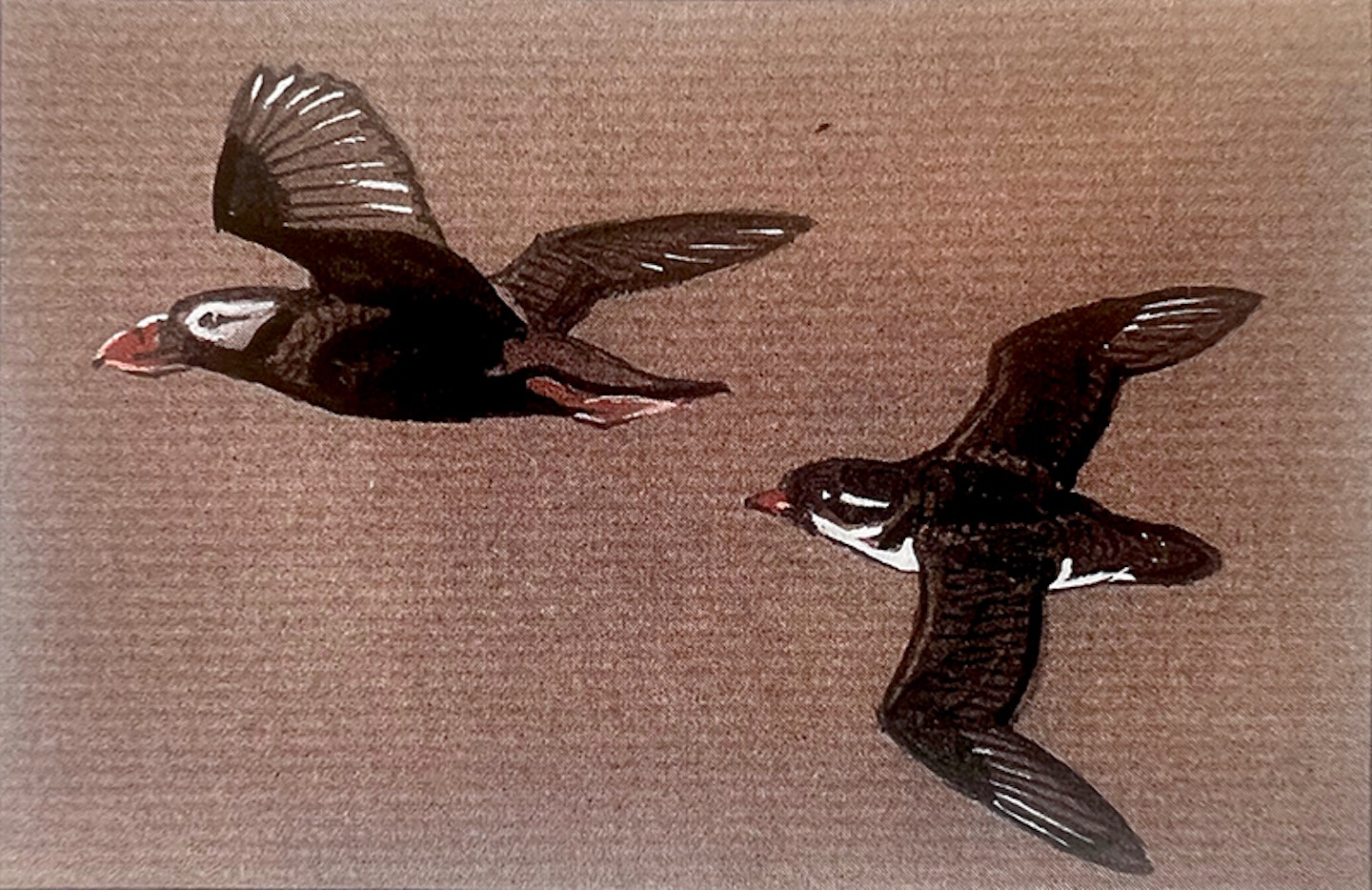

The auks and auklets swim as far as they fly and it is clear that those of the north Pacific have found an extraordinary vector as grail-like as our own long-sought ‘North-west Passage’. In the track of the Ancient Murrelet could come not only the Crested Auklet, the Parakeet Auklet, the Marbled Murrelet and the Tufted Puffin – all known from the North Atlantic east to Iceland and Swede – but also any of the other seven species that breed in the Bering Sea and adjacent area of the Pacific. [also Long-billed Murrelet]

“Keep your American field guide handy” seems another sensible maxim.

Altogether, I have discussed at least 37 and at most 44 seabirds that could reach Britain. For fuller information, I refer you to Peter Harrison’s two guides:

Seabirds: an identification guide. Croom Helm. 1983

Seabirds of the world: a photographic guide. Christopher Helm. 1987

To sea-watch without these excellent books nearby is sheer folly.

P.S. Earlier I mentioned the mysterious black-rumped petrels caught on the north-east coast of England. I am reminded that one such bird was reported from the Minch in the early 1950s. I do wish someone would tell us what they are!