May 1991

Pitfalls, morasses and a mystery

In the series that combines practical advice with wonderful story-telling, Ian Wallace wades this month into deeper and more troubled waters to discuss truly odd, and even impossible, birds.

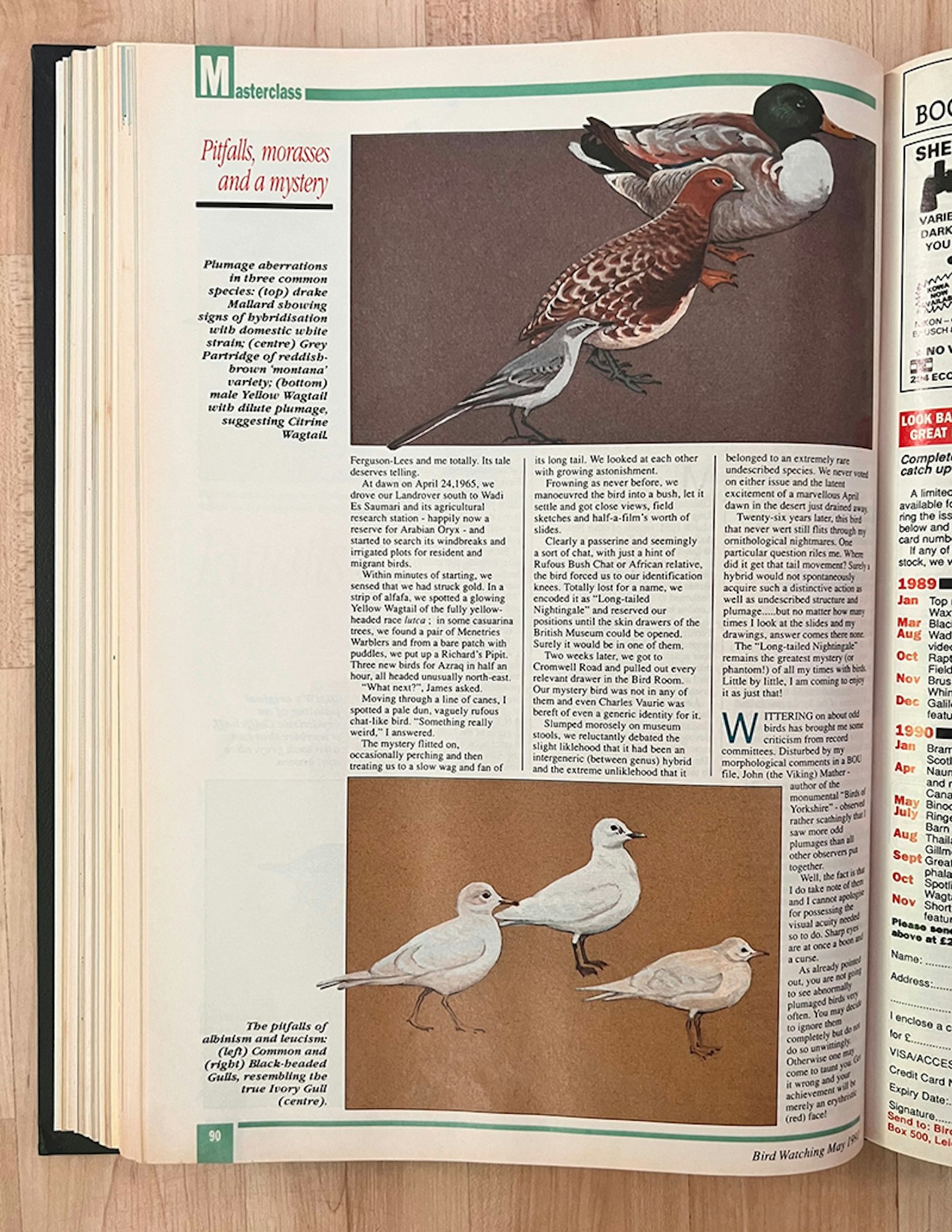

Look at a lot of birds and sooner or later you will see an odd one. All the way from a Mallard with a white chest (not a Shoveler) to a brick-red Grey Partridge (not a Red Grouse) or a Yellow Wagtail that is actually grey and white (not a Citrine) and onto many more such birds, the pitfalls of abnormal and aberrant plumages are dug for the unwary observer.

My early tutors did not warn me about avian oddities. Accordingly, as a youth, I became quite hysterical over a “black wheatear” that slowly but surely demoted itself to a Starling with a white tail.

From the mid-1950s, I also recall an excited dash with Dougal Andrew to another “black wheatear”, only to diagnose it finally as a Common (Northern) saturated in soot or ash. Classic examples of avian masquerades!

For a time in the same decade, British Birds turned its attention to albinism and other colour variations in birds. A flood of reports of white Blackbirds, pale geese and biscuit-coloured juvenile Starlings flowed into its office. Bryan Sage, then chief birdwatcher of Hertfordshire and prolific author, was appointed to collate the records.

The ensuing paper on aberrant plumages showed them to be too frequent for further individual attention. BB began to return the reports of oddities to sender. Accordingly, since the 1950s, there have been fewer and fewer references to peculiar birds and hardly any in field guides. The fact remains, however, that several types of plumage disorder and mutation present themselves and their potentials for confusion should not be under-rated.

Here are some brief notes on the commonest forms:

Albinism (total whiteness)

The complete absence of pigment from feathers and bare parts is rare. I have never seen this condition in a wild bird. Partial whiteness is quite frequent, being exhibited particularly by abundant species like Blackbird, Starling and House Sparrow. It is not necessarily caused by true albinism and may be more akin to the next plumage state.

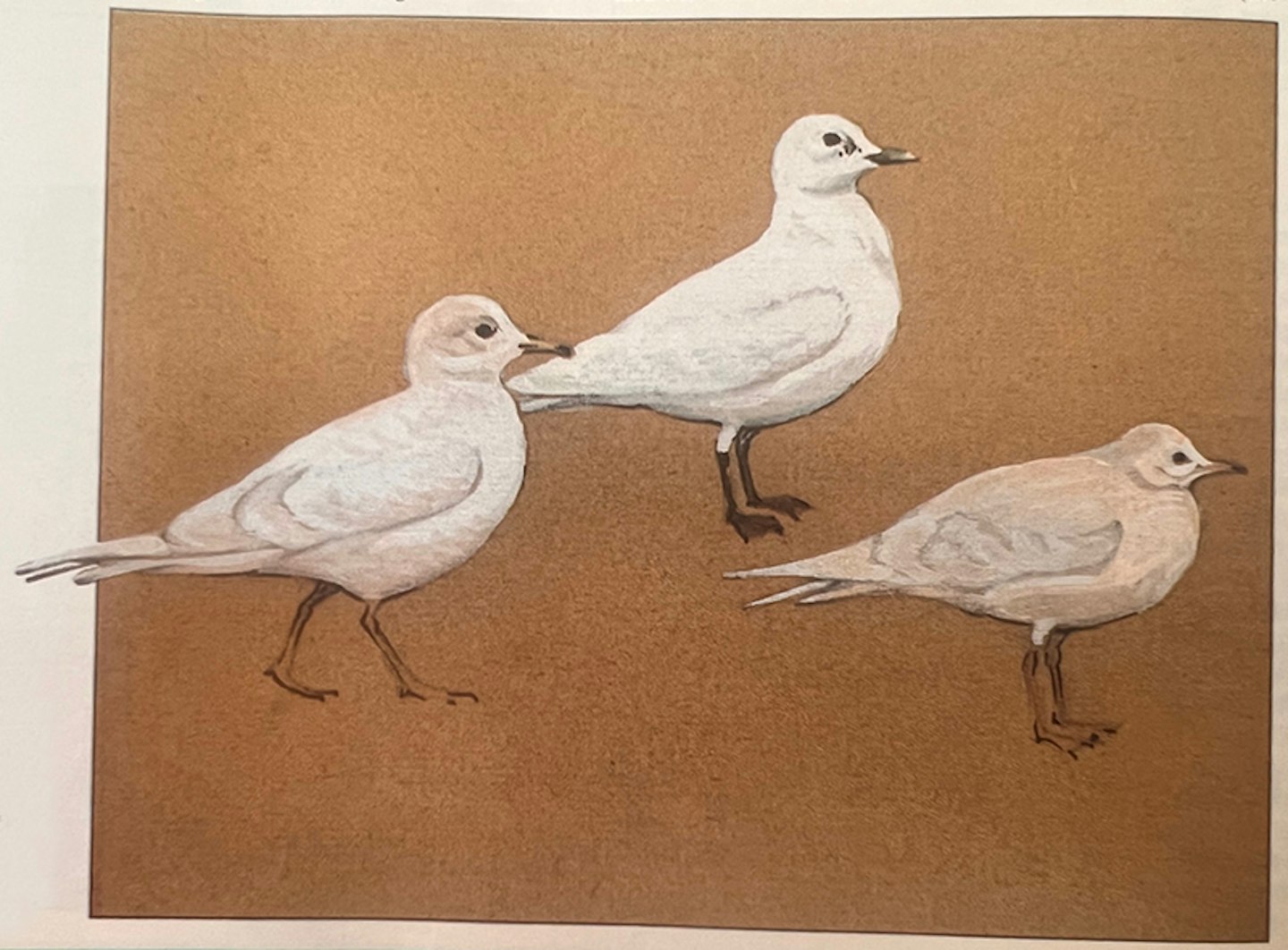

Leucism (increased paleness)

This is the effect of ‘pigment dilution’. Its degree varies considerably and the underlying plumage pattern is fully suppressed only in the palest examples. At least in some species, it is a product of poor diet. Like partial whiteness, it is quite common. I have seen for example pale Collared Doves and Woodpigeons and, worse still, ivory-coloured Black-headed and Common Gulls (neither Ivory Gull).

Melanism (increased darkness)

A condition mostly caused by a genetic excess of dark pigment. It may appear so regularly that the species exhibits a natural melanic form, as does the Montagu’s Harrier and the Snipe in its Sabine’s variety. It can also be induced by diet, for example in hemp-fed Bullfinches, and by adrenal imbalance.

Erythrism (increased redness)

This is not infrequent and like melanism, it may occur naturally, as in the Tawny Owl, or unnaturally, as in certain gamebirds. The most surprising example that I have seen was a red-brown Chiffchaff in Regent’s Park in 1959. It had me all over Vol. 2 of the Old Handbook for several hopeful but eventually empty hours!

Xanthochroism (increased yellowishness)

A rare condition, but a Canary-like appearance can afflict Yellow Wagtails and even some Phylloscopus warblers. L am never going to forget a golden-headed and -tailed Fieldfare near my home in the 1989/90 winter.

Endocrine and thyroid imbalance

Interruption of the pituitary gland’s function can produce male plumage on a female body. Variations in thyroxin levels can accelerate or slow and suppress moult. In the latter condition, alterations to colour and shade of plumage also occur, most notably in the partly-darkened, partly-bleached plumages of immature gulls and terns – contributing to the ‘p_ortlandica’_ syndrome* of subadult plumages explored by the late Peter Grant and Bob Scott in the early 1970s.

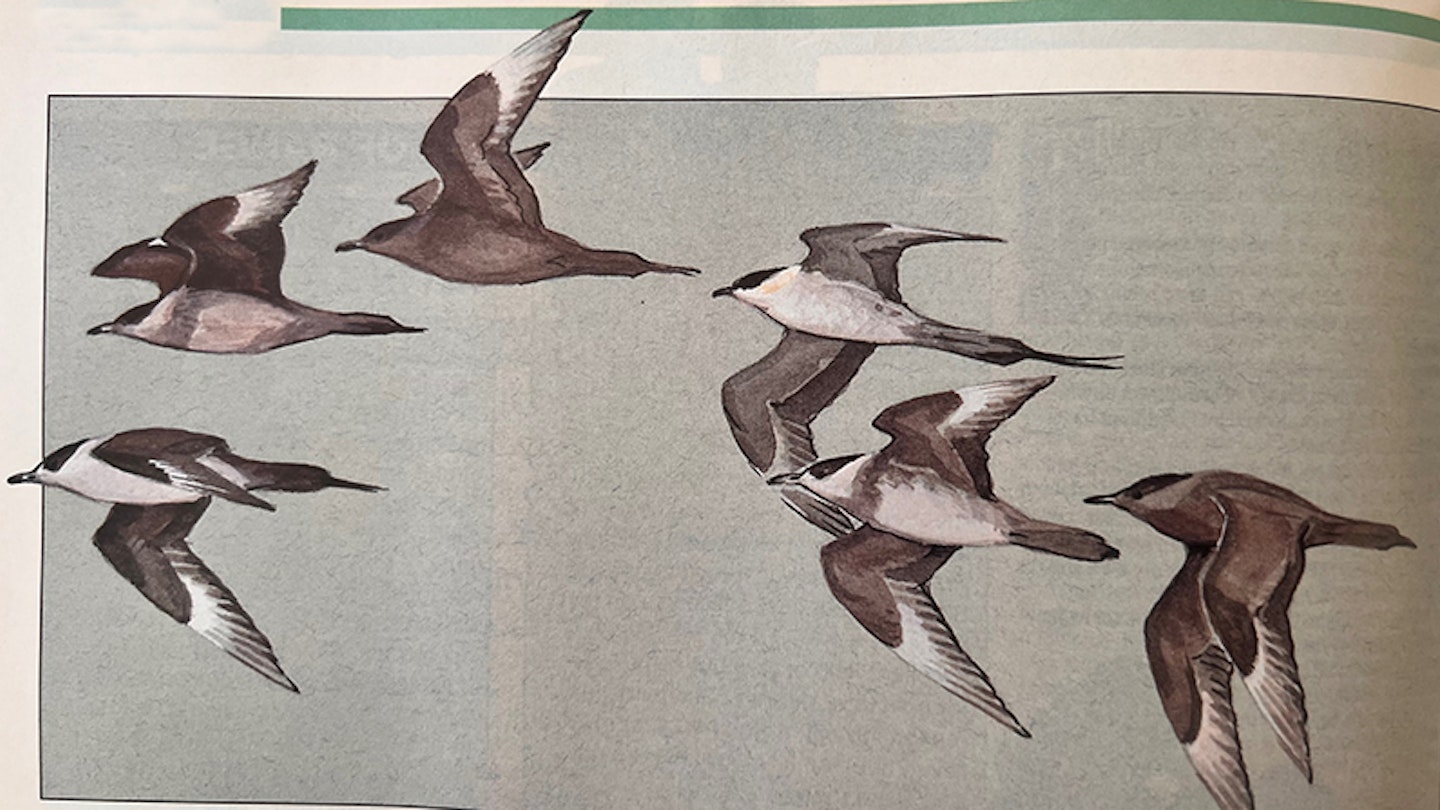

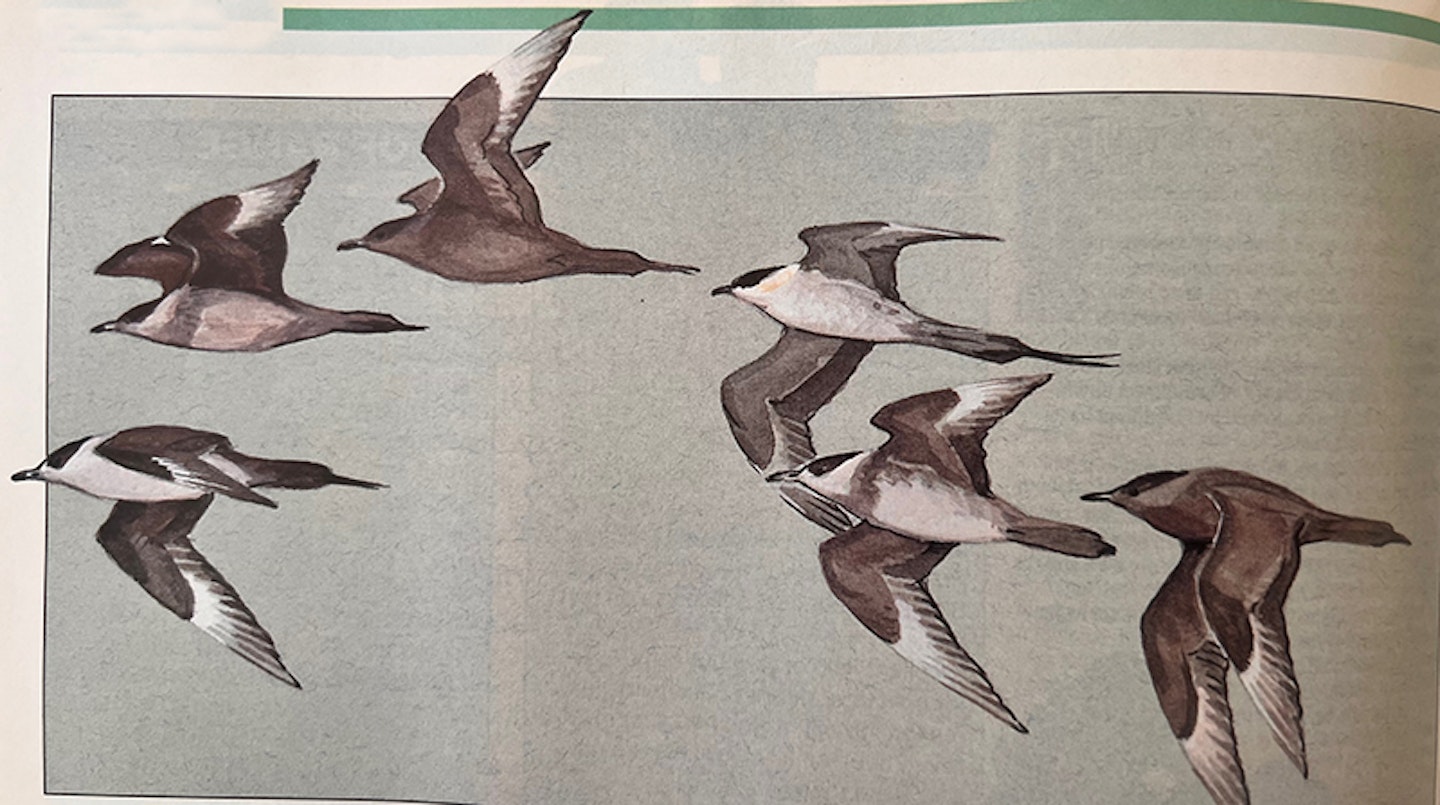

*The portlandica syndrome described oddly patterned or variegated plumage, particularly in immature terns.

Reapearance of ancestral characters

The cause of this state is difficult to prove, but undoubtedly a few birds appear to recover the characters of earlier prehistoric plumages or closely related species. Jays can show hints of their blue-barred wing covets on their crowns; immature Great Spotted Woodpeckers in Britain may exhibit the face and neck patterns of the Syrian and the red crop spot of its North African relatives. Even more surprisingly, Buzzards can not only be patterned like Rough-legs but also have feathered legs. In ducks, this phenomenon which stems probably from gene recombination is quite frequent. The white neck-ring of the Mallard can also be worn by Gadwall, Shoveler and even Teal!

Hybridisation

Successful breeding between two species is far more common than most birdwatchers suspect. Their hybrid young can lay low the most expert observer or ringer. Once again, it is wildfowl that lead in awkward crosses, with the northern geese and diving ducks producing annually some totally confusing progeny. Go to any wildfowl collection for ready examples. Hybridisation occurs in many other families, however, and it is particularly bewildering in warblers and finches. Experimentally, it has even been induced between the seemingly specialised Crossbill and the ordinary Greenfinch.

Variable plumage in the same species

Except for a few highly-decorated male birds like the Pheasant and the Ruff, which wear all sorts of colours and feather patterns, and some species like the smaller skuas that exhibit light and dark colour phases, Western Palearctic birds do not often present this pitfall. In the Tropics, however, male and female Parrots and bush-shrikes can wear very variable plumages, their colours and plumages suggesting totally different species. These are not the normal sexual dimorphisms (two plumages) of, for example, most finches and Sylvia warblers but dramatic disruptions of normal appearance. One shrike has the apt but daunting name of Many-coloured Bush Shrike. It occurs in five morphs, up to three of which can coexist in the same bushes!

Looking back over my near half-century in the field, I would judge that odd birds sporting one of the above plumage states have crossed my path every 100 days or so. Once understood, albinistic and leucistic birds are not difficult to sort out, but many of the other variants lay nasty snares.

My first trysts with hybrids came in the late 1950s. In the wake of the first Black Duck in Kilkenny in February 1954 and the first Ring-necked Duck at Slimbridge in March 1955, reports of other Nearctic ducks multiplied. Two were favoured as Lesser Scaups. I was not involved in the licensed but much disputed obtaining of one at Sutton Courtenay in 1958 ,but I was beckoned to a live bird at Barn Elms, London in January 1960.

The presence of a splendid drake Ferruginous Duck had produced close inspection of all the diving duck on the four square reservoirs. Eventually, one telescope “burn” found another unusual bird and the word went round that it could be a real Lesser Scaup.

I could not go immediately – due to James Ferguson-Lees insisting that the first available weekend should be devoted to West Hartlepool and its most famous avian visitor, a Dusky Thrush – but I did try to add something to the debate on 19 and 23 January.

On the first visit, Bob Scott and I failed to spot it, but on the second, Bill Conn found the bird bobbing about in a small horde of Tufties and Pochards. We adopted Yoga-positions, pulled our our long tubes and “burnt” it. It looked interesting, but when the sun came out, we saw for sure that its back was too dark and its head shone with a green lustre and not the necessary purple. The final damper was a white mark behind the nail of its beak.

So my best man and then closest birdwatching companion did not get, as hoped, two lifer ducks out of Barn Elms in one go. Gazing on a freezing morning at what was clearly a Scaup x Tufted Duck hybrid, we had only the “glowing warmth” of the Ferrugineous drake to cheer us up!

Odd ducks plague birdwatchers more than any other mixed-up birds. Over the last three decades, I have been perplexed by at least seven other hybirds. The most recent were a wigeon with white axillaries (= American) but “unpeppered” head (= Common), and a “Redhead” (=drake Ferruginous × duck Pochard), both in my local patch. So keep your wits about you in the presence of loose-living ducks. Their commonest hybrids are well described in the Macmillan guide.

Far worse puzzles can be set by other hybrids, particularly in passerine families. Last summer, Andrew Lassey showed me some slides of a large ‘Phylloscopus’ trapped at Flamborough and well photographed alongside a Willow Warbler. I peered and peered at it but like my friends, I was stumped. On size, it could have been a Willow × Arctic Warbler but if so, why was there no enhanced supercilium and no trace of a wing-bar? Along with FOG’s two amazing “mini-Chiffchaffs”. it went into history unnamed.

In the above two episodes, the genus of the birds was apparent, but once upon a time in Jordan – before the Azrag oasis was destroyed – a unique passerine tantalised James Ferguson-Lees and me, totally. Its tale deserves telling.

At dawn on 24 April, 1965, we drove our Land Rover south to Wadi Es Saumari and its agricultural research station – happily now a reserve for Arabian Oryx – and started to search its windbreaks and irrigated plots for resident and migrant birds.

Within minutes of starting, we sensed that we had struck gold. In a strip of alfafa, we spotted a glowing Yellow Wagtail of the fully yellow-headed race lutea; in some casuarina trees, we found a pair of Ménétries’s Warblers and from a bare patch with puddles, we put up a Richard’s Pipit.

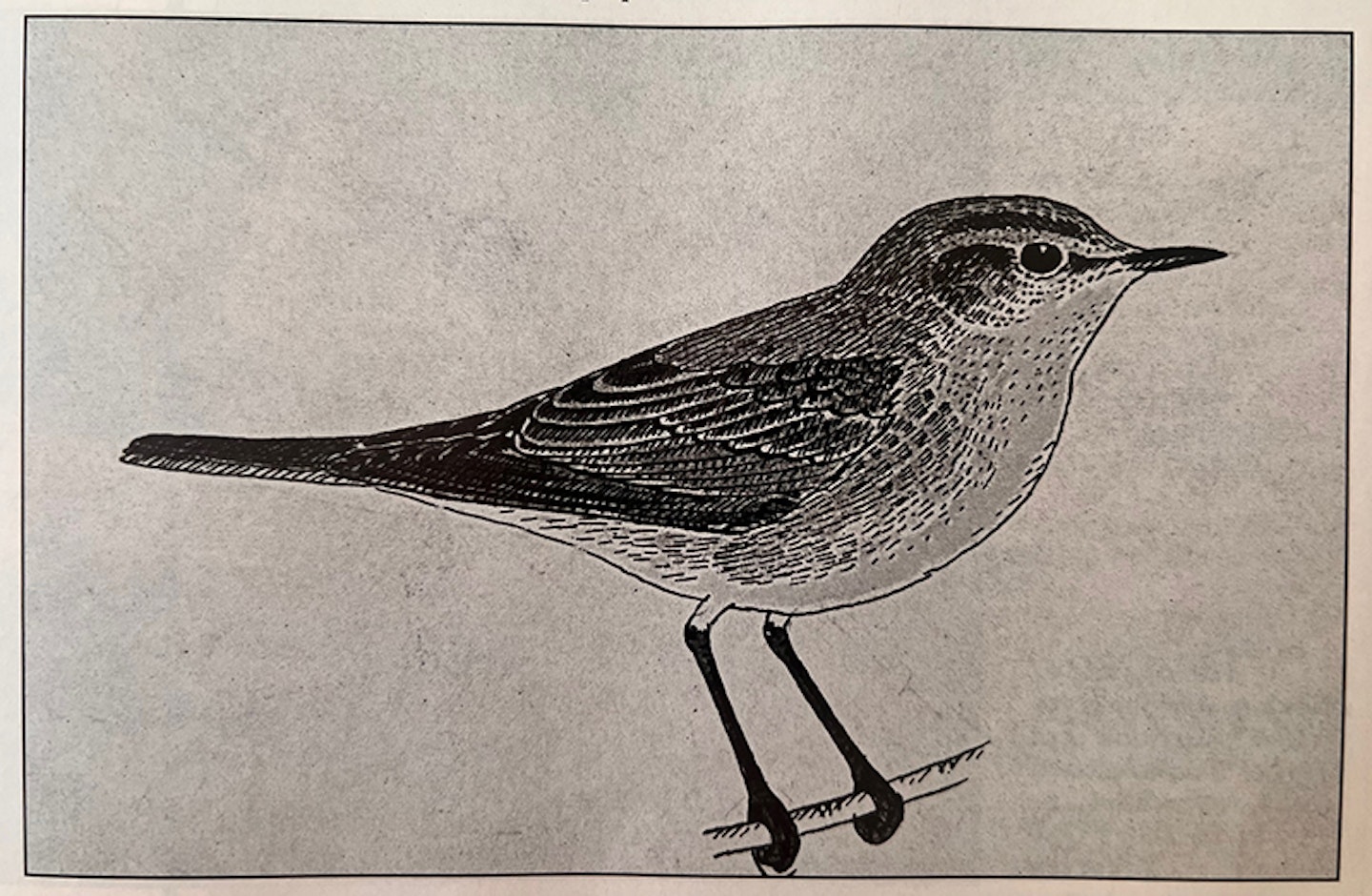

Three new birds for Azrag in half an hour, all headed unusually north-east. “What next?”, James asked. Moving through a line of canes, I spotted a pale, dun, vaguely rufous chat-like bird. “Something really weird,” I answered.

The mystery flitted on, occasionally perching and then treating us to a slow wag and fan of its long tail. We looked at each other with growing astonishment. Frowning as never before, we manoeuvred the bird into a bush, let it settle and got close views, field sketches and half-a-film’s worth of slides.

Clearly a passerine, and seemingly a sort of chat, with just a hint of Rufous Bush Chat or African relative, the bird forced us to our identification knees. Totally lost for a name, we encoded it as “Long-tailed Nightingale” and reserved our positions until the skin drawers of the British Museum could be opened. Surely it would be in one of them.

Two weeks later, we got to Cromwell Road and pulled out every relevant drawer in the Bird Room. Our mystery bird was not in any of them and even Charles Vaurie was bereft of even a generic identity for it. Slumped morosely on museum stools, we reluctantly debated the slight likelihood that it had been an intergeneric (between genus) hybrid and the extreme unlikelihood that it belonged to an extremely rare undescribed species. We never voted on either issue and the latent excitement of a marvellous April dawn in the desert just drained away.

Twenty-six years later, this bird that never wert still flits through my ornithological nightmares. One particular question riles me. Where did it get that tail movement? Surely a hybrid would not spontaneously acquire such a distinctive action as well as undescribed structure and plumage... But no matter how many times I look at the slides and my drawings, answer comes there none. The “Long-tailed Nightingale” remains the greatest mystery (or phantom!) of all my times with birds. Little by little, I am coming to enjoy it as just that!

Wittering on about odd birds has bought me some criticism from record committees. Disturbed by my morphological comments in a BOU file, John (the Viking) Mather – author of the monumental “Birds of Yorkshire” – observed rather scathingly, that I saw more odd plumages than all other observers put together.

Well, the fact is that I do take note of them and I cannot apologise for possessing the visual acuity needed so to do. Sharp eyes are at once a boon and a curse. As already pointed out, you are not going to see abnormally plumaged birds very often. You may decide to ignore them completely, but do not do so unwittingly.

Otherwise one may come to taunt you. Get it wrong and your achievement will be merely an erythristic (red) face!