May 1990

Making the most of your birdwatching – a new series

Sharing the Spirit

Birdwatching in Britain and Ireland is in pretty good heart, but its human universe is altering rapidly. Many of Bird Watching’s readers did not begin to watch birds until the 1980s. Thousands of beginners find it difficult to enter and enjoy a wonderful hobby as fully as my generation did.

In my January article ‘Birdwatching in the ‘80s’ we may have spotted the main reason for this situation – the now relatively tiny number of “trained soldiers” available to pass on both knowledge and skill to “recruits”.

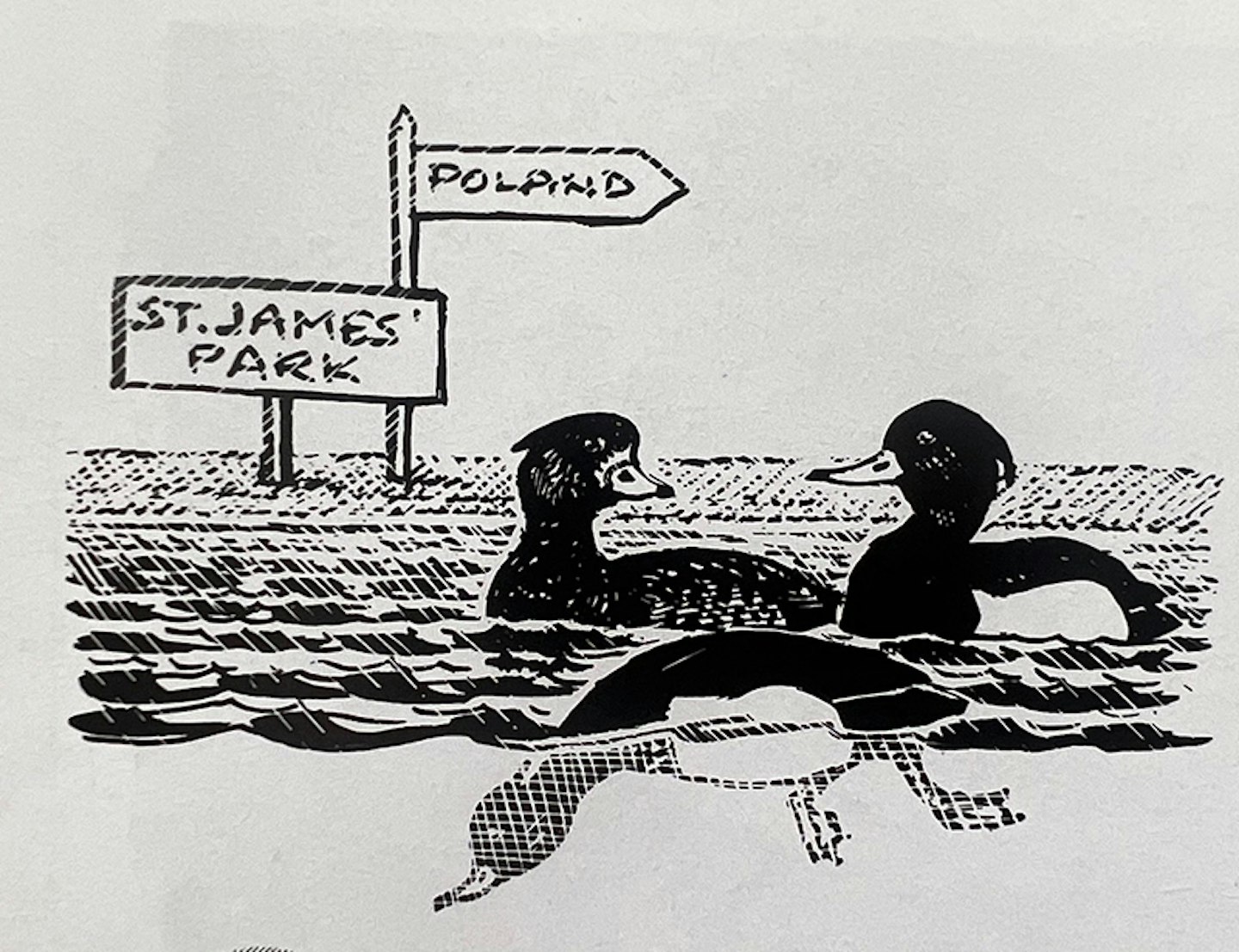

Forty-five years ago, I met my first “trained soldier” – a rather austere gent in a dark blue raincoat, called Roberts – on the bridge of the St. James’ Park lake. I was revelling in the aquatic antics of Tufted Ducks, diving directly under me, but I became truly amazed when Mr Roberts calmly announced that some had been proved (through ringing) to come from Poland.

My mind boggled as I looked afresh at East European birds plumbing Inner London water. They (and their species) had suddenly an additional magic property and I had acquired my first big lesson in how cerebral knowledge can enhance visual pleasure. In the late 1940s, I was fortunate to meet a succession of other coaches, including the senior arts master at my last school, the young Turks of the Edinburgh branch of the Scottish Ornithologists Club – most notably Frank Hamilton – and the officers of the ornithological section of the London Natural History Society – particularly Tony Gibbs, the most helpful bird recorder any young observer could have designed.

Looking back, I have to thank them all for the constantly longer and richer carpet of knowledge that they laid ahead of me and for the care that they took to see me not stray too far from its edges. Inevitably, I made mistakes but I was allowed to learn from them. Never once was I pilloried for babbling ignorantly.

The watershed of my early experience came in 1949. Eek (nickname, not call note) Turner, the schoolmaster, organised an April visit to the Isle of May. With hardly a migrant in sight, we became so desperate that we tried to turn the only Phylloscopus of the five days into a Yellow-browed Warbler.

We failed with that lunacy, but to soothe my wounds, I had the observatory logs to read. These revealed to me for the first time birdwatching in the round. Written by then great Scottish observers like Joe Eggling and Maury Meiklejohn, there was a lesson on every page and – courtesy of Maury – a joke on many. Here were not just tales of birds but evidence of joyous humanity by the dayful. Already motivated, I became really keen as we chased a few brave Wheatears towards the isle’s traps (only once into one) and still dreamt foolishly of a rare bird!

More windows onto field ornithology opened that autumn. Fresh from the just-emerging Fair Isle Bird Observatory came Kenneth Williamson to talk to my school’s ornithological society.

In one breath, he spoke of breeding skuas; in the next, he enthused over the (dreaded) Yellow-browed Warbler. I was so awestruck at his expertise and commitment that I managed only a grunt when I finally got to shake hands with the man who mixed the roles of plain hero and guiding light for many of my peers and especially me. To be his student on Fair Isle became my life’s chief goal, well, apart from exams!

The year 1951 crawled along, but at last one early September morn, we flew north. At Kirkwall Airport, a friendly man turned out to be no less than the Laird of Fair Isle, George Waterston himself.

Landed that night in south Shetland, our ornithological company became ever more famous as we munched mutton with Tom Henderson, who ran the staging post of the Spiggie Hotel, and my favourite log writers, Joe Eggling and Maury Meiklejohn. Somehow containing my excitement, I preyed on their every word and sneaked envious looks at Maury’s meticulously-kept field notebooks, full of mysteries like rosefinches and eastern buntings. In six short years, I was on the high slopes of an ornithological Mt Olympus and we were not yet on the magic isle!

Next morning, the “Good Shepherd” sailed south into a light SE wind and mist. “Could be good”, muttered George but did not explain why. The north sea had an oily chop to it but 2½ hours later, we reached North Haven. Fair Isle was one jump away. There to greet us was Ken, his wife (and great cook) Esther and the few observatory workers (under 10 in those early years). I was surprised to sex two of them as girls – on Fair Isle! – but it was a free world, I grudgingly conceded.

My first stay on Fair Isle was all that I had hoped. Ken was an inspiring teacher, if he liked you, and from him and his peers, I received the most concentrated schooling of my life. Courtesy of the SE breeze, there had indeed been a drift fall on top of a previous arrival of Greenland – Iceland birds and our week sped by, as we sorted out the avian proceeds.

Lessons in identification, bird trapping (no mist nets then), bird handling, ringing, racial variation, migration periods and so on were poured into me. I was having no luck with Lapland Bunting. Spotting my misery, Maury took me out, taught me how to spot areas of seed-bearing grasses and then re-launched me into the heather. Two grassy patches from restart and I had my lifer Lapp.

Another day I had come upon Maury and a non-Lapp, amorphous, large bunting. “You’ll have to define the colours, Ian”, he said, “I’m colour blind” and so gave me my first full responsibility in a rare bird record. And by the way”, he added, “upwind and downlight on this approach; you’ll see nothing if it streaks off or the sun blinds you”.

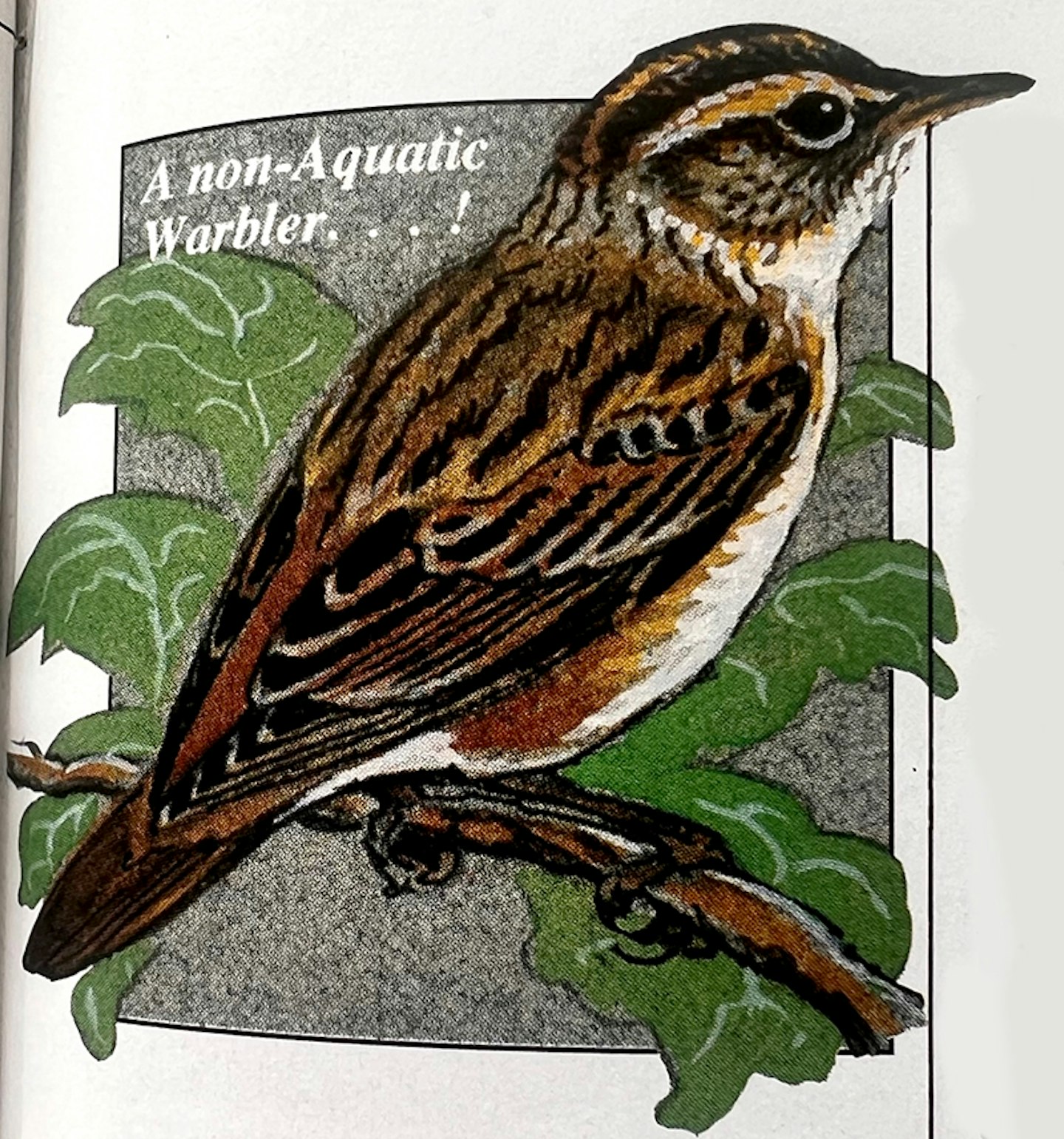

The bunting turned out to be a young Black-headed, then and now a major rarity, and I suffered no small rush of blood. On the next day ,seriously ill with rare bird fever, I found a streaked Acrocephalus, plunged in for Aquatic and ran for my betters and more glory. They walked the two miles back, leant on the stone dyke by the bird’s root crop cover, waited patiently for it to appear, knew instantly what it was and shrugged their shoulders as one man.

George came over to me and said slightly sternly, “Sorry, lad, but they’re not all rare; it’s just a Sedge”. I suffered the total pain of an exhibited, adolescent mistake and learnt another important lesson. High diving had no place in bird identification. It was time to go home!

That year also saw the beginning of my friendship with Douglas Andrew, then editor of the Edinburgh Bird Bulletin. It was one of the earliest and still my favourite local bird rag to which our school society contributed, and out of which contact I fell heir to a lifelong stream of superb letters, my first experience of a study area – Gladhouse Reservoir – and a laughing friendship still vibrant enough to embarass any restaurant.

Many other members of my generation could relate similar chains of inspiration and counsel and happily there are still some birdwatchers who freely share the wealth of their experience, particularly those who lead YOC groups. Nevertheless, the indications are that “trained soldiers” now number only three in each bird watching battalion of 100 people.

Accordingly, Dave Cromack has asked that my new task for Bird Watching should be to invoke the content and spirit of birdwatching before its currently explosive growth and to pass on to you some of the lessons learnt in a less madding, less twitchy time.

Working a patch

Contrary to myth, Dimwit (as Not BR calls me) has always spent more time counting common birds than chasing rare ones. Why? Because I get just as much, if not more pleasure from the first pursuit as the second, and because common birds set more lasting challenges. And how did I learn this? By working a series of patches hard, often daily, and making each bird universe mine alone or mostly so.

My patches or study areas have been as different as the Musselburgh foreshore in Lothian, the freshwater spring at the north end of Lake Nakuru in Kenya, Regent’s Park in Inner London, a sweaty stretch of the south-west Nigerian coast, Epping Forest and, in the 1980s, seemingly unremarkable farmland in the East Riding and East Staffordshire. I had some help in three of them but usually I have watched alone, shy of any distraction that would prevent my constant musing on the birds that appeared and their context of varying habitats and Changing seasons.

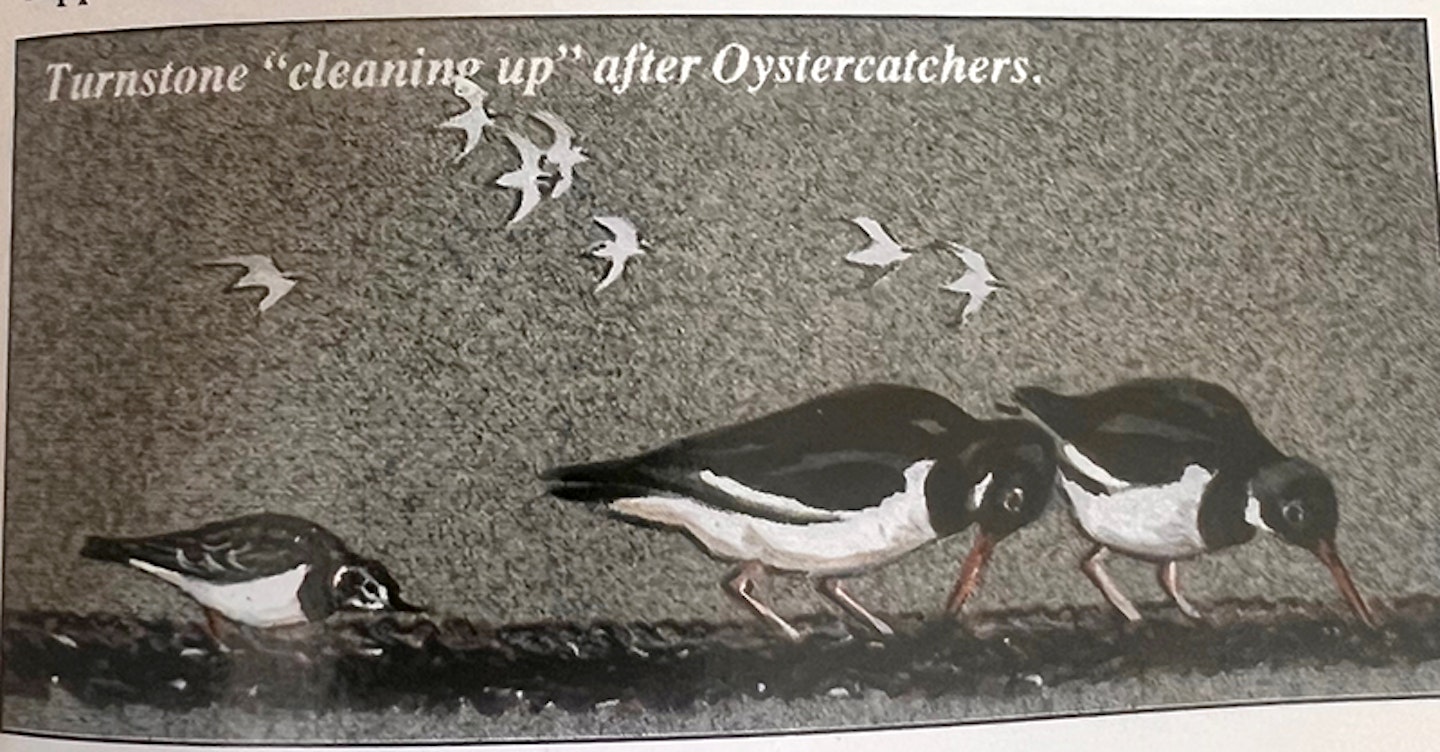

At Musselburgh, there seemed literally to be waders everywhere over the mussel beds and mud. Yet when I looked closer, it became clear that each species was staking separate claims: Oystercatchers opening mussels, Turnstones searching their debris, Grey Plovers on sandy bars, Dunlins on soft mud. I did not know it then but I was seeing an ecosystem in action, supporting a wide variety of species in remarkably small space.

In Regents Park, as the clean air act slowly released leaves from constant grime, insectivorous summer visitors took up residence and when the 1962/63 winter savaged most of Britain’s birds, the ‘heat isle’ of Inner London gave some protection to mine.

In Epping Forest, winter line counts defined the non-breeding profile of species – and their order of numbers – for the first time.

In my last two patches, fascinating changes in the breeding, migrant and wintering populations have never ceased. While some of my findings have been depressing – 14 breeding species going or gone in seven years in the East Riding – others have made all my growls about the at times sheer slog become whoops of triumph in a flash-witness a Bonelli’s Warbler in my orchard in late May!

So, how do you win experiences (and happy memories) for yourself? For a start, you have to commit to work. Studying an area fully does not sit easily with chasing the latest Birdline delicacy or just enjoying whatever bird comes along. It means scheming and then executing a quite complex but not difficult task – the description of the avifauna of one place in all four seasons. For most of our weather vagaries to have their effect, you should keep going for seven years. Reads like a sentence; do not worry; if you keep faith for a year, you should be so hooked that you will not want to stop.

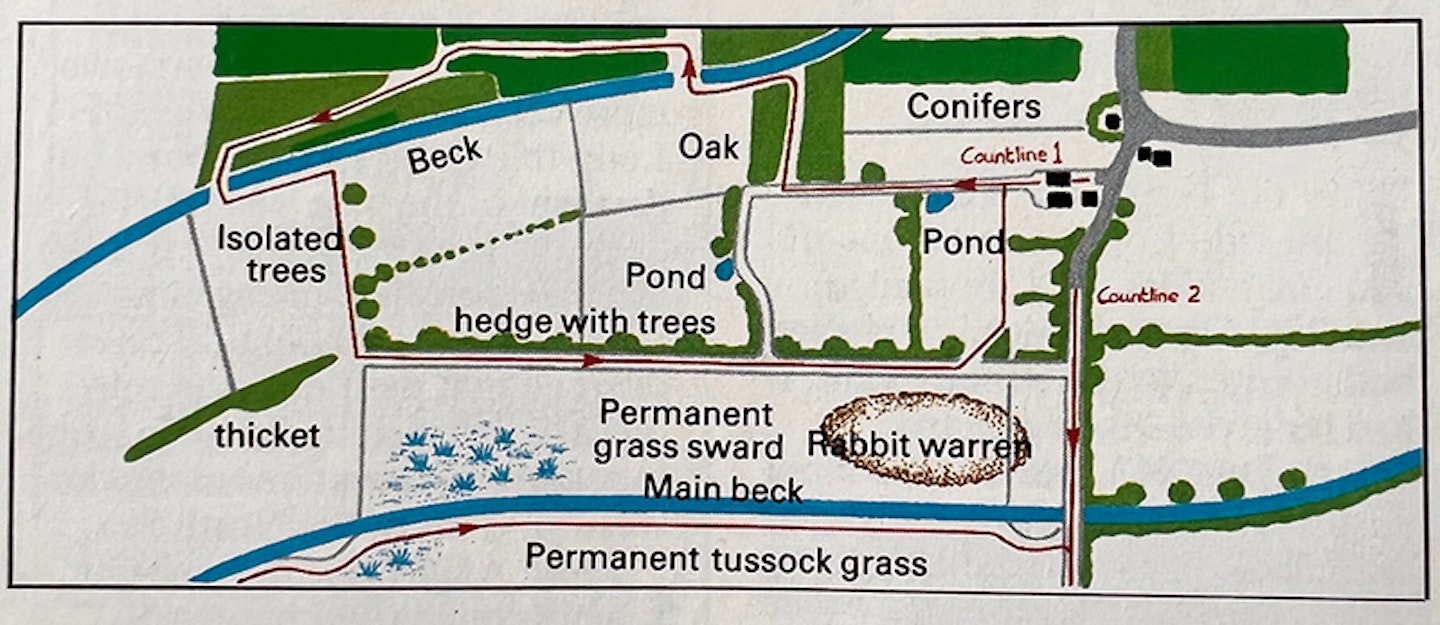

Where do you start? By picking your own patch or study area. Buy a large scale map (at least 1” to the mile) of where you live and look on it for some mixed habitat that you can visit easily and regularly. Better, initially, to start with a fairly small area (500 to 1,000 acres) and not over-stretch yourself. An urban park, a suburban playing field cum allotments, a piece of farmland, an interface of wood and moor, an inland water – there should be an option in such places near most homes.

Next, visit your chosen patch and check that it does indeed have a mix of habitats hedged fields, woods, at least one pond large enough to support waterbirds, some permanent grass, an interface of buildings and open space try for at least four types to insure a diversity of species.

Next, bring your map up to date and trace a copy on which you can define the boundaries of your patch and later your count routes.

Next, decide on your search and count routes within the patch. Almost inevitably you will find yourself counting birds both along lines and across spaces but that will not matter, provided that once set, you do not vary your discipline and so obtain comparable results. Try to include sunlit lees (the east sides of thickets and woods) for small migrants, water surfaces and edges for waterfowl, fields on both sides of hedges for partridges and larks and close passes of any unusual habitat such as a reedbed.

With any wood, include both a probe into it and a pass along it. Then test count your route(s) and explore the rest of the patch. You may spot where a change of route will give a fuller view of the bird population but make such changes only once, whatever later habitat losses count. Dither about and your results will not be comparable. Map your final routes.

Next, decide on the frequency of your study. One patch visit, with a full set of counts, every weekend is an ideal basic rhythm but during the two migration seasons, daily observations in some part of your area are essential if you are to see bird movements at all fully.

For migrant watching, it helps to get car access to your patch. In my East Staffs area, I am allowed to drive to a watch point over the local trout lake and round most of an airport. Car watching is not essential but it helps particularly on weekdays, when your job has to be done, too.

At my airport, I have cut my count time from 70 to 25 minutes and I get closer to the birds in my grey, mobile hide! Now, crucially, decide how you are going to log your data. I use boxed paper for all standard counts, with species ranged in the left margin and dates across the page, and enter all other counts in a diary, insuring that for my migrant spots my register is again constant.

If other chores appear, for example the need to describe an uncommon bird or piece of behaviour, these are done on separate sheets. This division of record allows easy summary and photocopying at the year end. Next (and second last), prime your mind and eyes with what is already known about the birds likely to occur on your patch.

There are three “musts”: references, the summer and winter atlases of the BTO and your county ornithology. Get these from a friend or library and steep yourself in them. Then prepare lists of potential species.

This exercise will sharpen your wits and target your goals. Assuming that you stick to your task, your last and most enjoyable chore will be to prepare an annual report on the birds of your patch. This should take the form of an annotated systematic list and include comment on every species, even sparrows.

Your local recorder will find your summary of great value and only simple sums will allow you to work out for example the incidence of passerine birds within the various habitats (line counts divided by line length, expressed as birds per kilometre), the total numbers of wildfowl (actual counts from surveyed waters) and presence in or passage through fields of plovers (again actual counts).

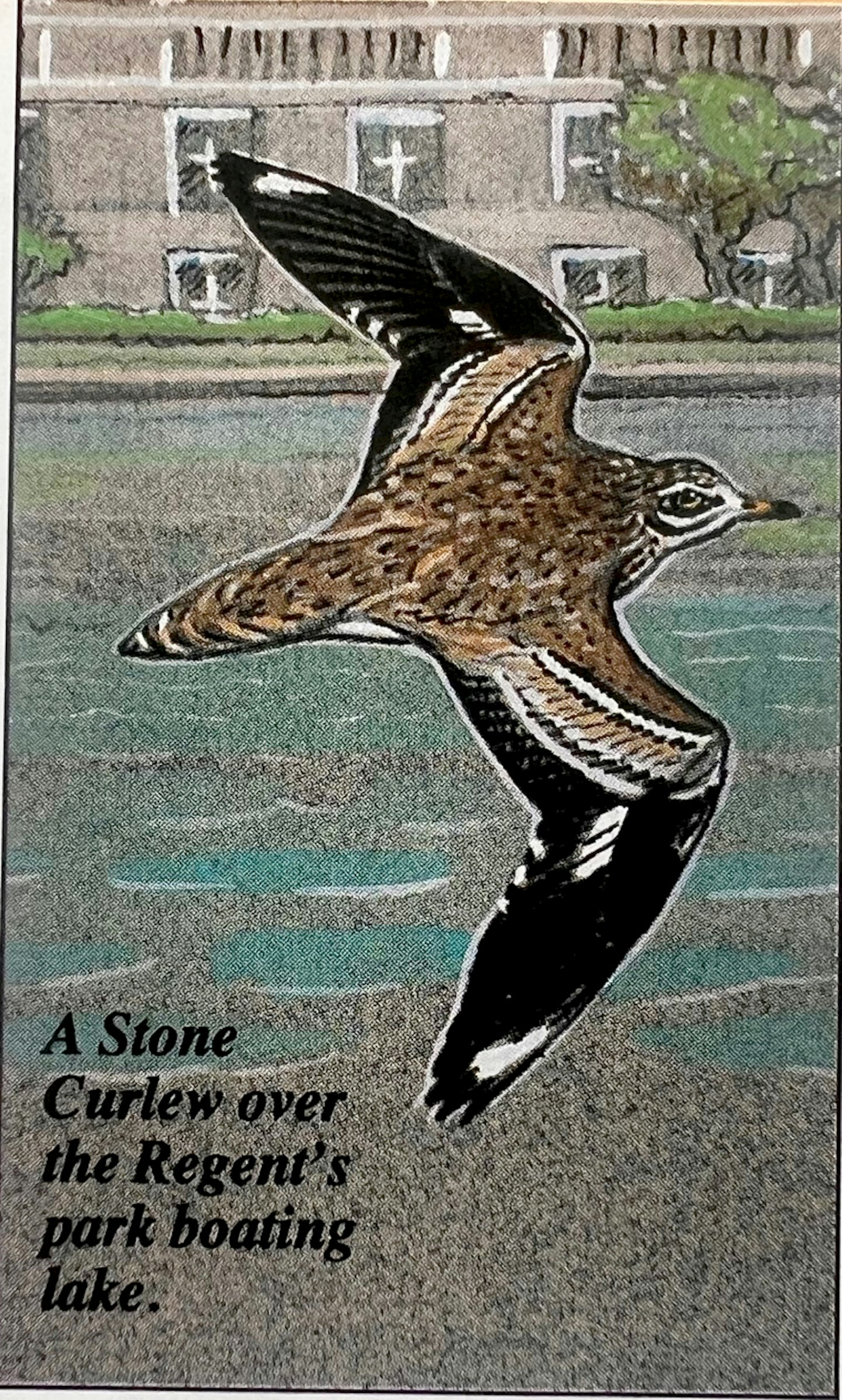

With any luck, you will make local news every year and certainly you will contribute significantly to the fund of conservation data that is so important to bird survival. “But will I see anything special?”, I hear you plead. Well, it depends. In my 19 year association with Regent’s Park, an ill-judged lie-in after five early visits cost me a Black-eared Wheatear (Then only the 14th for Britain) but my other patient ploddings produced a high-flying heron that looked Purple to me, a Bewick’s Swan, almost annual Smews, a Montagu’s Harrier and an Osprey (then as uncommon as many current so-called rarities), a Stone-curlew skimming over the lake (yes, really), a large pipit that did not call, a Water Pipit (feeding on butter), the odd Nightingale, a wing barred Phylloscopus (not an eastern Chiffchaff) and a merry band of irrupting Crossbills.

Alright, I accept that they did not give the British Birds Rarity Committee sleepless nights but hang about. How about also the arrival of breeding Great Crested Grebes and Grey Herons, the presence of breeding Pochards (now listed as a rare breeding bird), bird-hunting Kestrels, thousands of migrant Woodpigeons (pouring across the dawn sky) and falls of up to 100 night migrants? Realise that all these events were ringed by the grey buildings of a huge city and perhaps you will understand how exciting they were.

Within my study of about 90 regular species, each was a significant discovery or milestone along the way! In my later study areas, with about 120 regular species, uncommon birds have continued to produce bursts of adrenalin and renewals of enthusiasm. True, I failed in a major bid to prove Short-toed Treecreepers in Epping Forest in 1972 (through one was accepted from there in 1975) but otherwise more patch persistence has produced Honey Buzzard, annual Goshawks, Rough-legged Buzzard, Red-footed Falcon, Peregrine, Lesser Golden Plover (before the split), Great Snipes and Glaucous Gull, to mention only some non-passerines which gave themselves up among all the common birds.

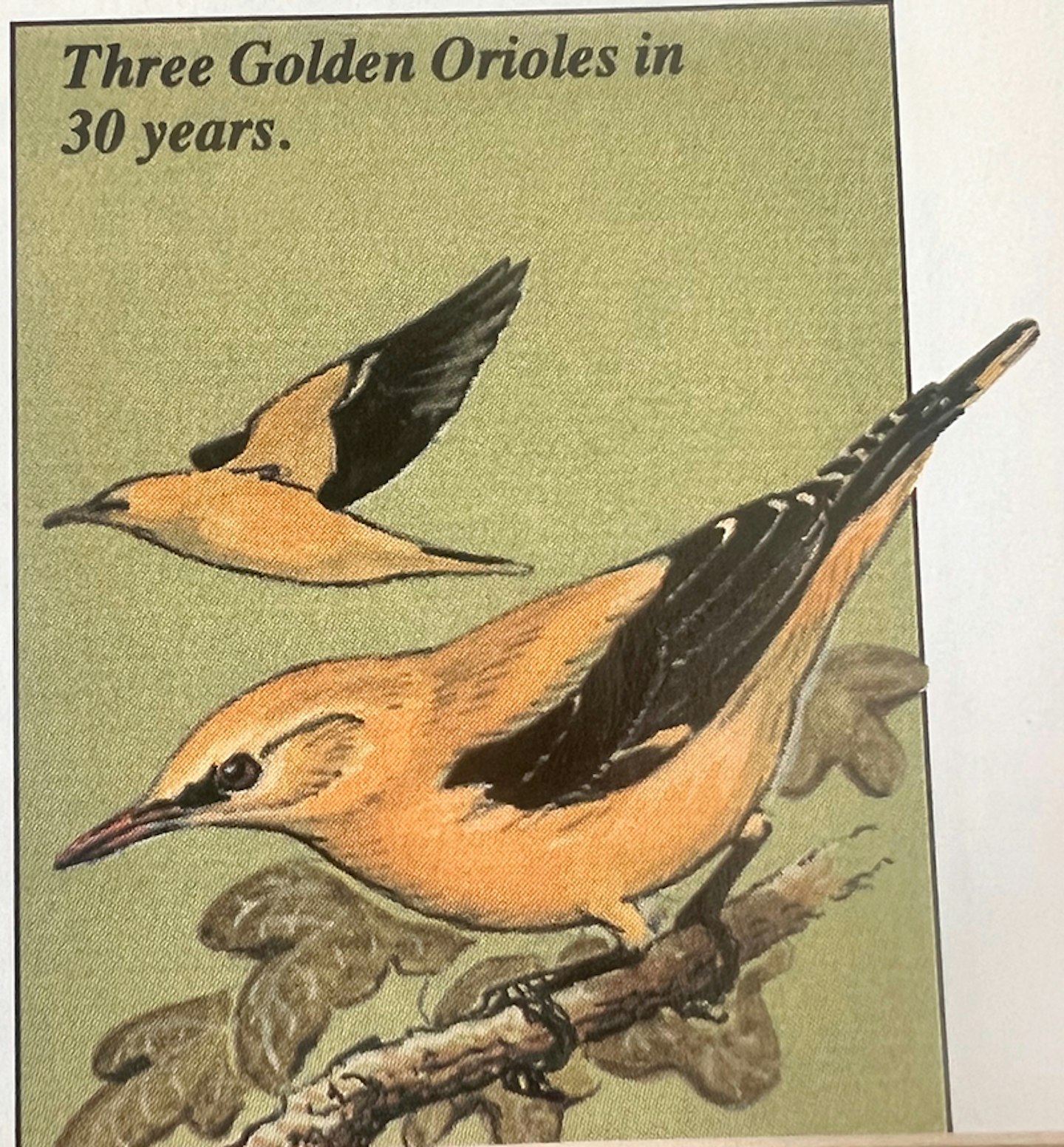

Still not convinced? Alright, how about three Golden Orioles, each good for years of redoubled effort?! So, whether or not your patch will supply you with not only a growing understanding of an avian community but also the occasional self found rarity, is a question that you can answer best for yourself.

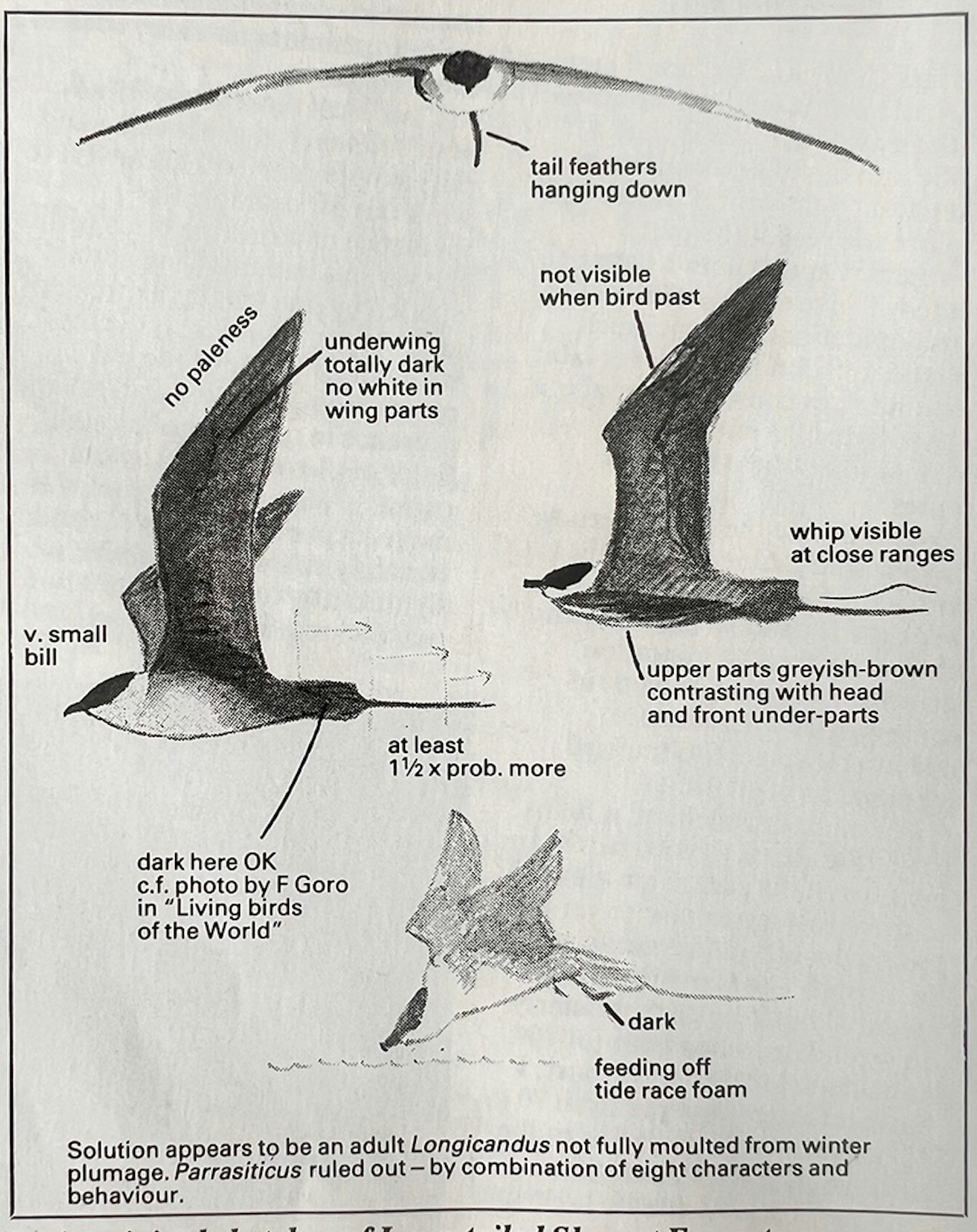

“Time in equals (eventually) good bird out” I firmly believe and I freely admit that the chance of one helps keep me at common bird counting. Building a case, in the 1950s, I had visited north Norfolk for some long days. Cambridge Bird Club’s leader Ian Nisbet had pointed to distant birds and I had believed his finger. In November 1963, however, I came unstuck with a small Arctic Skua off Suffolk, so I deleted Long-tailed from my British list.

On 27 May 1967, dawn in Gloucestershire brought an end to a wild night but grey clouds and S wind persisted. I decided to watch the morning bore fill up the Severn estuary off Frampton, north of Slimbridge. John Saunders was there before me and had an immature Gannet for his pains. I was surprised to see 24 Sanderling. Something was up!

At 1040, a skua appeared and made one slow close pass. Pale Arctic? Maybe, but the longer I looked at it, the more Long-tailed it became. Curses, it went back into the murky basin. John had also spotted it but even together, we could not name it. I fretted all day and at 1700 I just had to try again, even in pouring rain. My luck was in.

A small, dejected skua was standing on the north edge and I slowly walked up to, well, actually over it. At ten feet, I could see every feather. Several wet sketches and many notes later, I left it in peace and later wrote in my log, “I shall have to ask around but for the moment, Long-tailed seems the better answer”, The moment lasted and I re-instated my rubbed out tick.

Over the next seven years, two more certain and three probable Long-taileds crossed my bows but then out of the blue, the BBRC decreed that the species was a difficult rarity, requiring national review. The ornithological fates decreed that their decision was quickly followed by the 1976 surge in seabird observations along the western coast of the North Sea. From August 21, the embryo Flamborough Ornithological Group started to rewrite many Yorkshire records and surely we were seeing really small skuas.

Andrew Lassey, Irene Smith and I debated our dilemma which consisted mainly of total doubt that the Long-tailed Skua was in any way rare. There was nothing for it but to build an unshakeable case and hope to be released from the tedium of mega descriptions. So we gave every small skua total attention, wrote copious notes, drew scores of sketches, read every reference (all rather thin), argued, checked skins, involved our YNU peers, wrote yet more notes and so on.

Yes, the birds were small, they slinked along, did not chase other seabirds, had narrow wings, It rarely long tails, etc, etc, and persisted in force-feeding our perception of a fourth skua species. They had to be Long-taileds and thank God, the other observers who came to share our breakthrough agreed.

By October 30, my own haul was 48, with eight off Kinnaird Head in Grampian and 14 windblown into Bridlington Bay my top day scores. The BBRC allowed most of them and as elsewhere along the east coast, other observers had also “crashed the barrier” of prior ignorance – our case was not only built but the general cause was totally secured. Fairly smartly, the Long-tailed Skua became again what it has probably always been – a not uncommon passage migrant that is not easy to see only due to its pelagic nature – and not a bureaucratic rarity.

Thinking back on our effort, it seems now rather excessive. At the time, however, it was firstly great fun to be taking the BBRC on and secondly a classic example of how close working observers can combine their skills to prove a positive point. Sometimes, of course, the reverse procedure is necessary.

I hold to my own reasons for thinking that the BBRC’s revision of Greenish Warblers was a bit heavy-handed but there can be no doubt that it had to be done. The bogey of northern, actually mostly eastern Chiffchaffs with wing-bars, had stalked us all for over 25 years. The day just had to come when some Greenish lost their capital letters.

What cases might you build? Here are some positive possibilities that could be worth pursuing – seabird passage down Islay’s west coast (probed in the late 1970s but since?): inland breeding by Cormorants (surely soon? [certainly now! Ed]). Duck members in farmland (even now, more than we think?) Kestrel status (“fairly sedentary” said the BOU in 1970 but I have always lost half of mine or more every winter). Feral breeding of Red-legged Partridge (does it continue?). Hybridisation of Golden and Lesser Golden Plovers (happens? increasingly?) – and, switching to the other end of the list, these feeding heights of Swallow and House Martin (how much overlap?), off-passage periods in migrant chats do they have autumn “fattening” places?), behaviour of Whitethroat (less common, we know, but less extrovert too?) and upland wintering by Linnet (function of food availability or temperature?).

As you can see, there is no shortage of questions and the degrees of answer difficulty are made enough to allow every one from careful beginner to full expert to have a go. As I said in January, the world of birds is our oyster. By building a case, by working a patch, you can find pearls for yourself. One last piece of advice: if you do decide to tackle a target subject like those above, it will make sense to check what other research is being done within your county.

This precaution will save you from duplicating other work and may well bring you sharper, closer-orientated advice than I can give in this injunction. Please do try and become a “trained soldier” we do not have enough of them these days. P.S. In working a patch, beware trespass. Always ask your local landowners for right of access.