Seasonal shake-up

April 1990

In the last three decades, April has often been a cold, wet, dreary month, delivering a strange mix of birds. In the last of his monthly reminiscences, Ian Wallace relives two experiences that feature first the month’s ability to prolong winter and second its eventual inability to withhold spring.

The North Sea, 1-3 April 1977

In 1976, mother’s Christmas gift to my family was an “early spring mini-cruise” to Norway. The brochure promised Scandinavian food and drink. and constant jollity and the majestic Norwegian coast, and I assumed there would be some birds, too. Maybe even a wandering sea eagle.

So, on 31 March, we drove to Newcastle, conscious of a vicious cold spell gripping Britain, but blissfully presuming it would not affect our marine adventure. At Tynemouth, the wind was SSW 6-7. Low clouds and mist merged indistinguishably and dusk fell as we left the harbour-mouth behind.

Up and out at 0610 to find the MS Bolero ‘steaming’ (‘dieseling’ doesn’t write right) west, under lowering clouds and with a brisk SW 6 lashing the decks with large rain. I jammed myself against a warm extraction vent and tried to seawatch.

Fifty minutes later, I had a miserable 16 birds of only three species; 60 more minutes and I had amassed a mere 44 of six species. Not one was interesting.

I wrenched myself off the vent, stumbled along the deck and descended rapidly into a Norwegian breakfast. On the way back up, I consulted with the ship’s second officer on the weather. With only a hint of apology, he announced that the Bolero was moving west in league with a warm front. There would be more rain, in due course, fog and probably snow! My ornithological morale plunged but I couldn’t eat any more, so I struggled back to the vent and tried again.

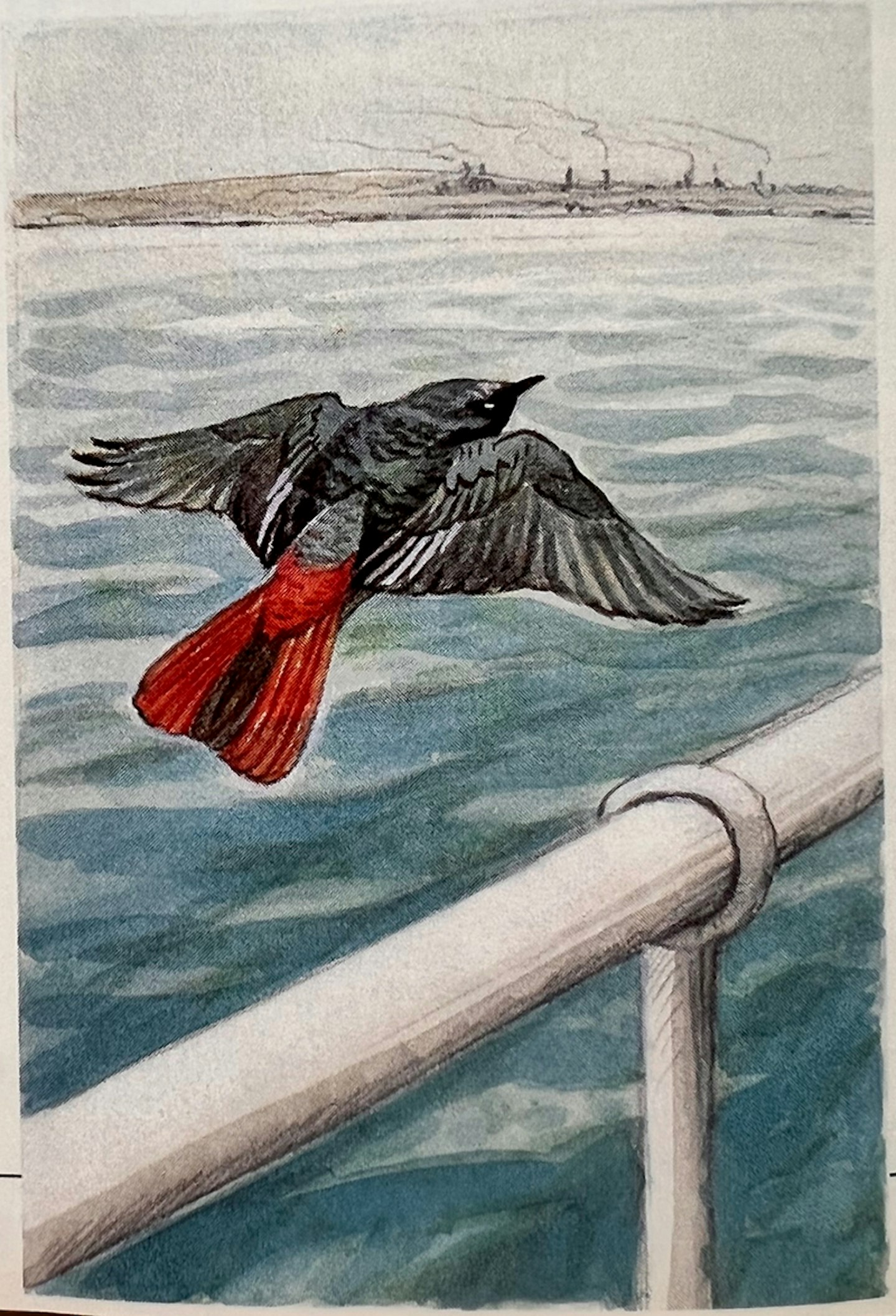

Between 0910 and 1000, visibility improved and trade was quite brisk. Ninety-five birds of nine species appeared, including the three common auks, a very large blue Fulmar among 40 ordinary ones, and a totally disorientated Dunlin, which circled the ship six times between 0945 and 1056 – suffering the waste of energy that is common in total occlusion.

In contrast, the one passerine that showed – an arrogant looking Starling – steered steadily SE at 0931. Was something about to happen? No, it was not. During 2¼ out of the next four hours, only 68 birds of seven species appeared. Only one was new, a Rock Pipit which flew E at 1100.

Bored rigid and cold stiff on one side, I deserted post at 1315. What was I doing in the North Sea, counting only Common Gulls? There was nothing for it but more food and drink. True to forecast, the next day’s weather was even worse. The fog was almost total, a dawn peer producing only 10 birds of four species.

By 0620, there was simply no visibility beyond the deck rails. The fog then proceeded to merge with rain, sleet and finally huge soft snowflakes. The majestic Norwegian coast consisted of glimpsed grey rock slabs and harbour towns. By dawn on the third day, we could not face yet another meal, but mercifully I was not hungover from the ‘restore the nerves’ drinking of the previous evening.

Summoning the will for a last exposure, I struggled onto deck and found that, mirabile dictu, the wind had shifted to NW 4, with rain still in it, but doing a great job clearing the fog. So, I proceeded to the friendly vent and tried again a moving seawatch.

From 0616 to 0700, seven birds of three species; from 0700 to 0750, 12 of five, but another ‘blue’ Fulmar was fun and a Gannet, new for the voyage (cruise be damned). After coffee, I tried again. Amazingly, the horizon was a full half-mile away and at long last I was able to stand at the bow. Just as on the 1st, bird traffic became quite brisk in the next 50 minutes. In a total of 32 individuals, eleven species were identified. An Oystercatcher circled us four times between 0925 and 1015 (utterly confused like the Dunlin) and a Purple Sandpiper landed beside me. A SW-directed movement of Kittiwakes began and at 0930 two Meadow Pipits went over.

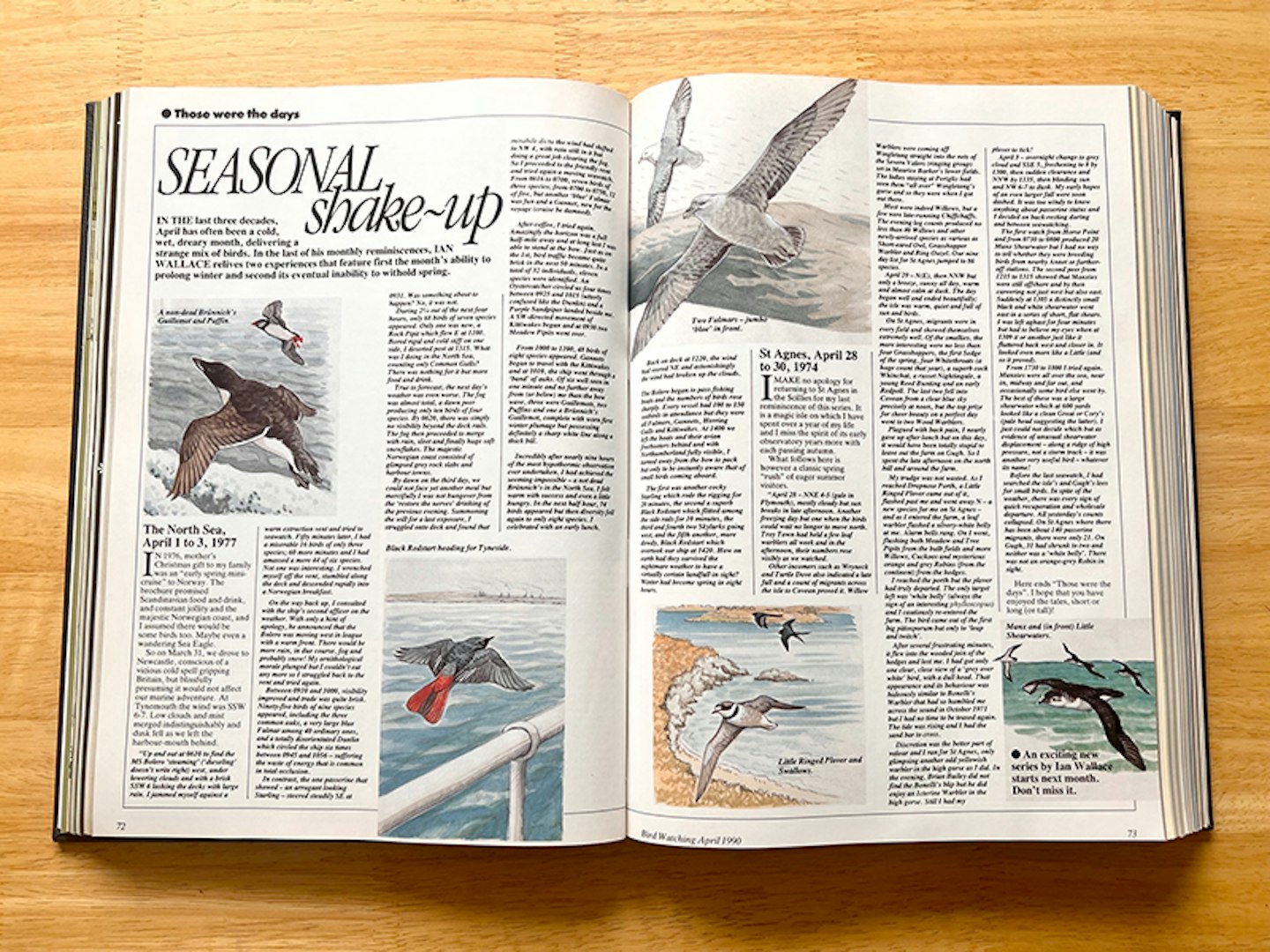

From 1000 to 1100, 48 birds of eight species appeared. Gannets began to travel with the Kittiwakes and at 1010, the ship went through a ‘band’ of auks. Of six well seen in one minute and no further away from (or below) me than the bow wave, three were Guillemots, two Puffins and one a Brünnich’s Guillemot, complete with worn first winter plumage but possessing definitely a sharp white line along & thick bill.

Incredibly, after nearly nine hours of the most hypothermic observation ever undertaken, I had achieved the seeming impossible – a not dead Brünnich’s in the North Sea. I felt warm with success and even a little hungry. In the next half hour, 74 birds appeared but then diversity fell again to only eight species. I celebrated with an early lunch.

Back on deck at 1220, the wind had veered NE and, astonishingly, the wind had broken up the clouds. The Bolero began to pass fishing boats and the numbers of birds rose sharply. Every vessel had 100 to 150 seabirds in attendance, but they were all Fulmars, Gannets, Herring Gulls and Kittiwakes. At 1400, we left the boats and their avian freebooters behind and with Northumberland fully visible, I turned away from the bow to pack but only to be instantly aware that small birds were coming aboard.

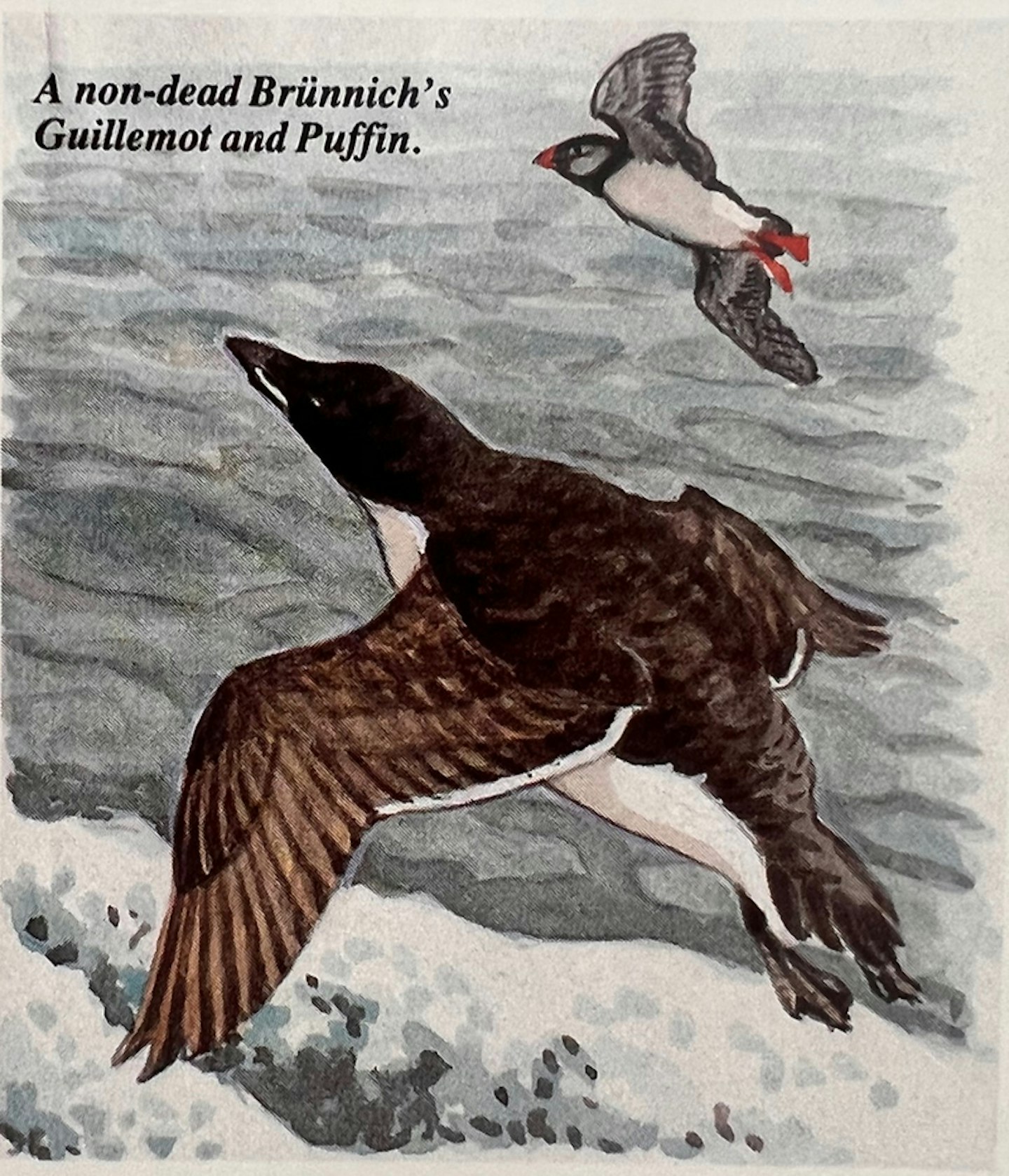

The first was another cocky Starling which rode the rigging for 20 minutes, the second a superb Black Redstart which flitted among the side rails for 10 minutes, the third and fourth two Sky Larks going west, and the fifth another, more dowdy, Black Redstart, which overlook our ship at 1420. How on earth had they survived the nightmare weather to have a virtually certain landfall in sight? Winter had become spring in eight hours.

St Agnes, 28-30 April 1974

no apology for returning to St Agnes in the Scillies for my last reminiscence of this series. It is a magic isle on which I have spent over a year of my life and I miss the spirit of its early observatory years more with each passing autumn. What follows here is however a classic spring “rush” of eager summer visitors.

28 April – NNE 4-5 (gale in Plymouth), mostly cloudy but sun breaks in late afternoon. Another freezing day but one when the birds could wait no longer to move north. Troy Town had held a few leaf warblers all week and in the afternoon, their numbers rose visibly as we watched. Other incomers such as Wryneck and Turtle Dove also indicated a late fall and a count of migrants across the isle to Covean proved it.

Willow Warblers were coming off Wingletang straight into the nets of the Severn Valers (ringing group) set in Maurice Barker’s lower fields. The ladies staying at Periglis had seen them “all over” Wingletang’s gorse and so they were when I got out there. Most were indeed Willows, but a few were late-running Chiffchaffs. The evening log counts produced no less than 40 Willows and other newly-arrived species as various as Short-eared Owl, Grasshopper Warbler and Ring Ouzel. Our nine day list for St Agnes jumped to 86 species.

29 April – N(E), then NNW but only a breeze, sunny all day, warm and almost calm at dusk. The day began well and ended beautifully; the isle was warm, quiet and full of sun and birds. On St Agnes, migrants were in every field and showed themselves extremely well. Of the smallies, the more interesting were no less than four Grasshoppers, the first Sedge of the spring, four Whitethroats (a huge count that year), a superb cock Whinchat, a russet Nightingale, a young Reed Bunting and an early Redpoll. The last two fell into Covean from a clear blue sky precisely at noon, but the top prize for sheer beauty on a perfect day went to two Wood Warblers.

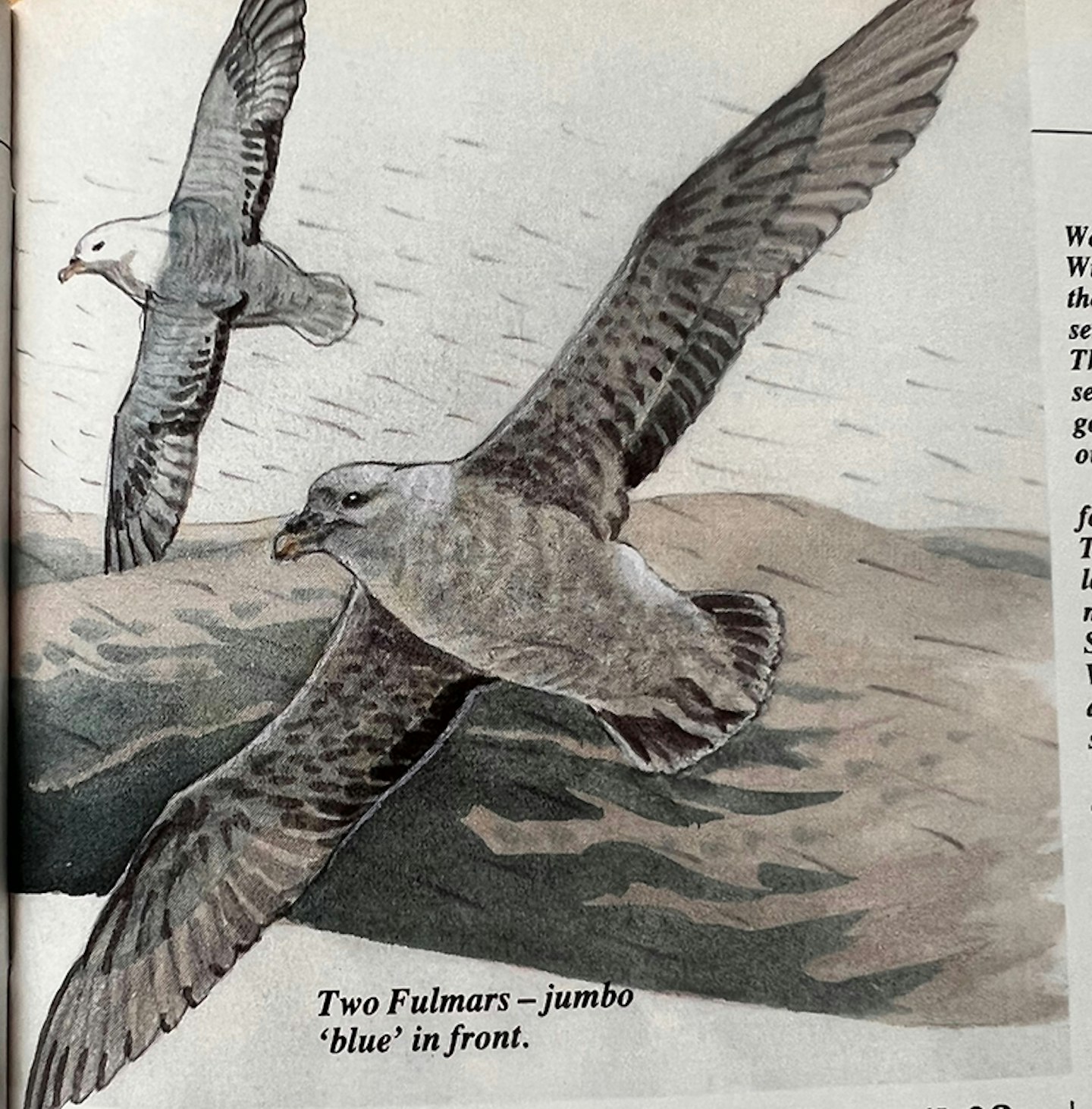

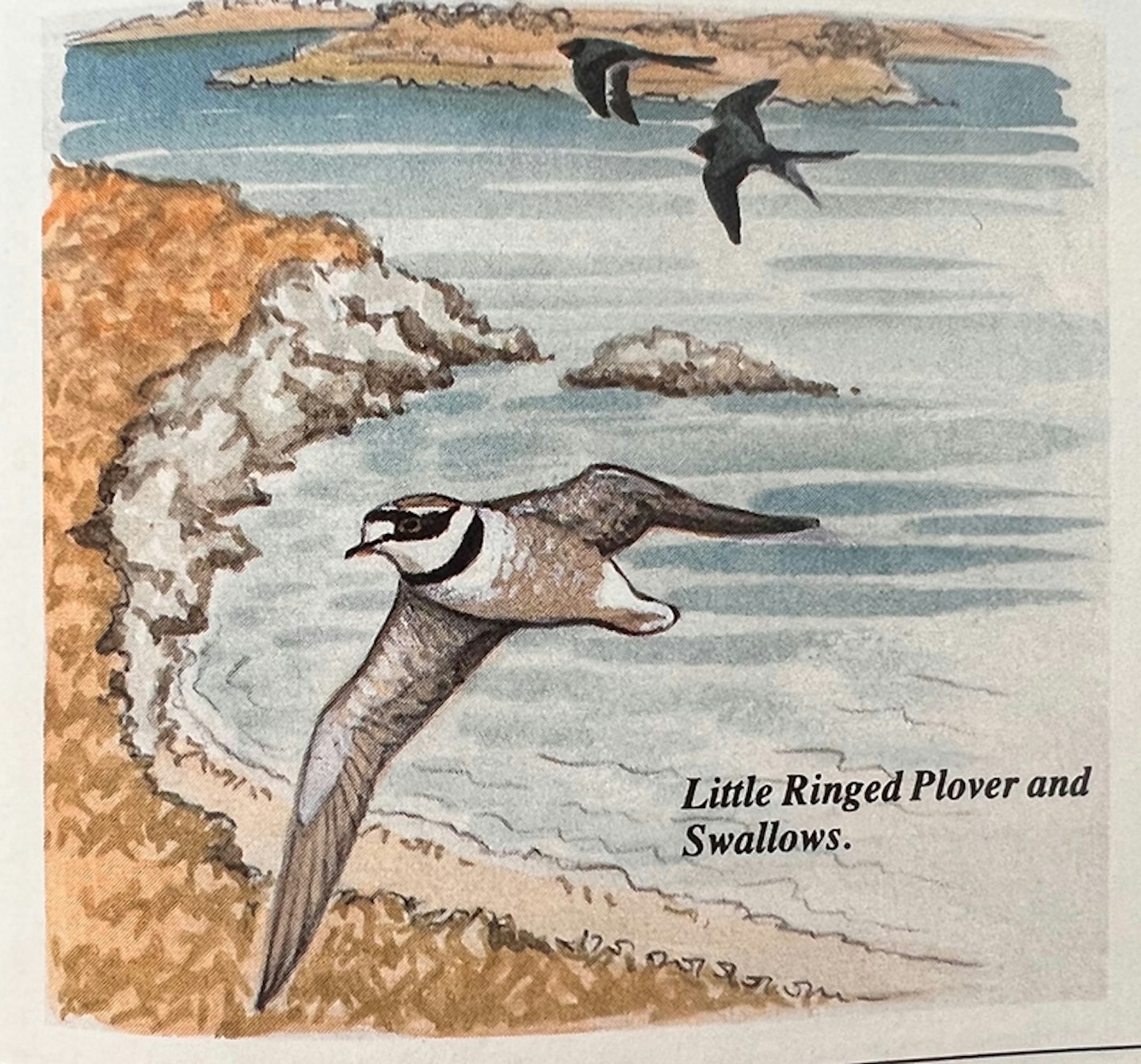

Plagued with back pain, I nearly gave up after lunch but on this day, it would have been totally stupid to leave out the farm on Gugh. So l spent the late afternoon on the north hill and around the farm. My trudge was not wasted. As I reached Dropnose Porth, a Little Ringed Plover came out of it, flashed past me and went away N: a new species for me on St Agnes, and as I entered the farm, a leaf warbler flashed a silvery-white belly at me. Alarm bells rang.

On I went, flushing both Meadow and Tree Pipits from the bulb fields and more Willows, Cuckoos and mysterious orange and grey Robins (from the continent) from the hedges. I reached the porth, but the plover had truly departed. The only target left was ‘white belly’ (always the sign of an interesting Phylloscopus) and I cautiously re-entered the farm. The bird came out of the first big pittosporum but only to ‘leap and twitch’.

After several frustrating minutes, it flew into the wooded join of the hedges and lost me. I had got only one clear, close view of a ‘grey over white’ bird, with a dull head. That appearance and its behaviour was hideously similar to Bonelli’s Warbler that had so humbled me across the sound in October 1971, but I had no time to be teased again. The tide was rising and I had the sand bar to cross.

Discretion was the better part of valour and I ran for St Agnes, only glimpsing another odd yellowish warbler in the high gorse as I did. In the evening, Brian Bailey did not find the Bonelli’s blip but he did enjoy an Icterine Warbler in the high gorse. Still I had my plover to tick!

30 April – overnight change to grey cloud and SSE 5, freshening to 8 by 1300, then sudden clearance and NNW by 1335, then blinding sun and NW 6-7 to dusk. My early hopes of an even larger fall were soon dashed. It was too windy to know anything about passerine status and I decided on back-resting during and between seawatching.

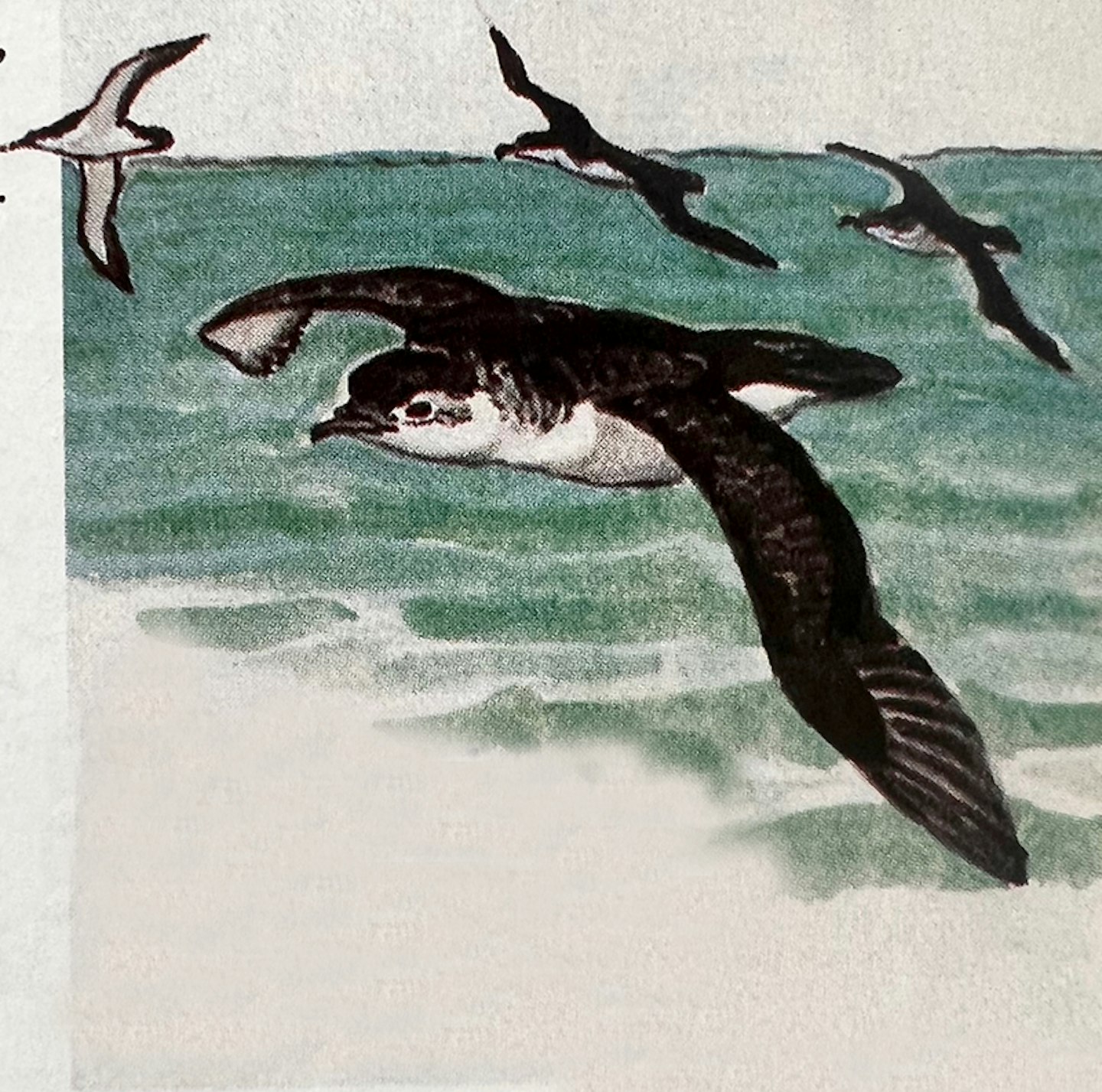

The first watch from Horse Point and from 0730 to 0800 produced 20 Manx Shearwaters, but I had no way to tell whether they were breeding birds from nearby Annet or further-off stations. The second peer from 1215 to 1315 showed that Manxies were still offshore and by then careering not just west but also east. Suddenly, at 1305 a distinctly small black-and-white shearwater went east in a series of short, flat shears. I was left aghast for four minutes but had to believe my eyes when at 1309 it or another just like it fluttered back west and closer in. It looked even more like a Little (and so it proved).

From 1730 to 1800 I tried again. Manxies were all over the sea, near in, midway and far out, and occasionally, some bird else went by. The best of these was a large shearwater which at 600 yards looked like a clean Great or Cory’s (pale head suggesting the latter). I just could not decide which, but as evidence of unusual shearwater displacement – along a ridge of high pressure, not a storm track – it was another very useful bird – whatever its name!

Before the last seawatch, I had searched the isle’s and Gugh’s lees for small birds. In spite of the weather, there was every sign of quick recuperation and wholesale departure. All yesterday’s counts collapsed. On St Agnes where there has been about 140 passerine migrants, there were only 21. On Gugh, 31 had shrunk to two and neither was a ‘white belly’. There was not an orange-grey Robin in sight.

Here ends “Those were the days”. I hope that you have enjoyed the tales, short or long (or tall)!