July 1989

One Albatross, several ponies

Continuing his personal reminiscences, Ian Wallace picks up two half-tales from his July logs. Both feature somewhat prehistoric rarities, set among a host of commoner wildlife.

July is not among my favourite months for birdwatching. I plug away at my local breeding birds, watch for early-withdrawing summer visitors (actually available from at least 10 July) and indulge in some warm sea- watching but often my summer log entries are thin.

Only by going back to the magic 1960s – all Stones, Beatles and no more than a handful of observers, anywhere! – did I stumble on two that do convey the unusual avian promises of high summer.

The first concerns a fabled seabird; the second tells of some truly expert observers and their study of our rarest breeding raptor.

Bass Rock 23 July, 1967

Sula bassana [ed: now Morus bassanus] is the Latin name for the Gannet and the adjective stems directly from its best known breeding site – a huge volcanic plug that rises abruptly out of the sea off North Berwick and is called the Bass Rock.

It is a place of double fascination to me. My part-Stuart blood is always stirred by the rock's heroic occupation by the last unsurrendered Jacobites, and my affection for seabirds was kindled by my first clamber up into the roof-top gannetry and terrified peers down the auk and Kittiwake-lined cliffs.

By the late 1950s, I had gone on from the Bass to other seabird colonies, even the ultimate St Kilda conglomerate, and I might never have returned to it but for one totally misplaced tubenose the first of its kind to sit down on British rock and only the second ever to touch ground in the Northern Hemisphere.

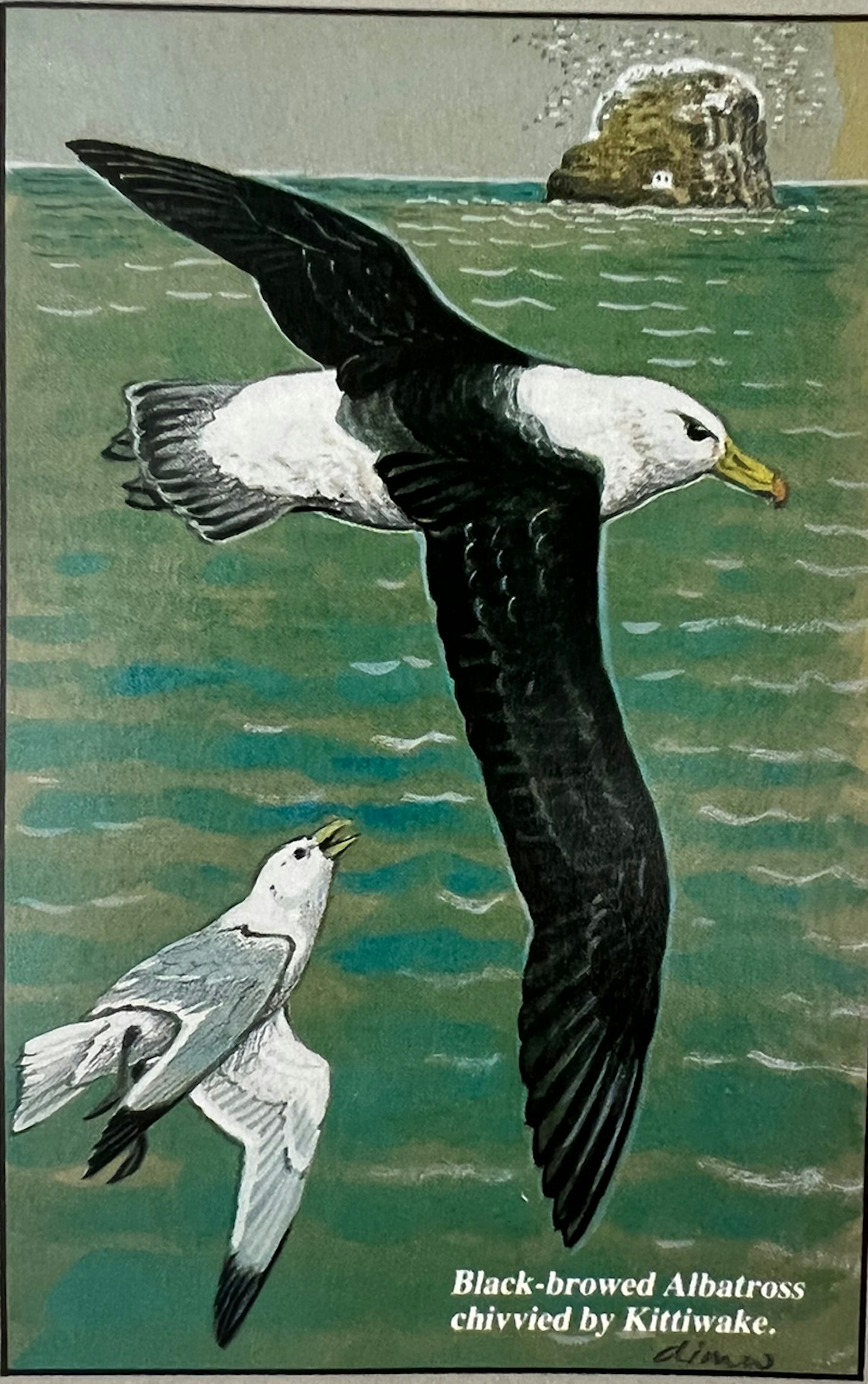

This bird was our seventh Black-browed Albatross, which had first appeared off the Bass in May and amazingly taken up station on the edge of the gannetry, so repeating the remarkable performance of an earlier bird that consorted with Faroese Gannets from 1860 to 1894!

My resolve not to go to tick it off finally broke in July. Phone calls to Dougal Andrew (Scottish ornithologist and mentor to me) and Mother on the 22nd confirmed respectively that the mollymawk (group name for ‘small’ Albatrosses) was still on the rock and that I could have a quick bed on the way there.

The journey north was horrendously slow but after a few hours kip, I revived and pelted down to North Berwick, complete with Mother who had decided also to see “an Ancient Mariner's victim” as she put it. The south shores of the Forth were as usual full of birds and my adrenalin was unstoppable when the Bass appeared on the horizon. The early morning was cool and cloudy but with the sea calm, we would at least be certain of landing.

By 0810, Fred Marr's boat had filled up and off we chugged, heading straight for the rock and straining for the big bird. Terns flew by, two Grey Plovers went south over us and an opportunistic Fulmar circled the boat, clearly hoping for fish offal but having to settle for sandwich corners.

As we neared the rock. the chorus of thousands of seabirds grew loud. Our glasses scanned the cliffs. The honour of spotting THE bird went to Roger Charlwood. Yelling a triumphant “it's there!” he pointed up and sure enough, on the low east cliff was the quite superb Black- browed Albatross. We drifted right under it and as if to greet us, it sailed off the cliff and over our heads. Adjectives flowed in its praise; to me, it really was a magnificent beast.

Fred Marr took the boat right round the rock, treating us to splendid views of all the faces of the Bass – crammed with nine other species of seabirds – and also two Common Seals, whose puppy-like faces bobbed up only a few feet way. The sun came out to improve the day further. Coming alongside the landing steps was no problem and we leapt onto them.

A prolonged bout of filial waving to departing Mother cost me a close look at the now relanded Albatross on the ground but soon the giant petrel was “to- and froing” in front of us at only a few score feet. In the improved light, its immaculate plumage and glowing orange bill were very striking. Not all that large, its wings were vis-a-vis Fulmar relatively short and narrow. The primaries ended in sharp points and the greater wing length was from shoulder to carpel joint, yet its flight was both powerful and effortless!

As we enthused over it with much back-slapping, the bird sloped off. I worried a bit. Having lugged my heavy camera all the way from Gloucestershire, I had forgotten to even point it at the bird. Had the chance for a photograph gone? A Great Skua passed to the north but it was no substitute.

Then, glancing down, I spotted the albatross on cliff patrol below us. Completing my study of the bird, I settled to its capture on film. Aim, swing, click, aim, swing, click – with the bird filling the screen, it was definitely “Hosking, beware” time for Wallace the photographer. Twenty exposures later, the bird ended its photo-opportunity by flying off to Fidra, a rock isle to the west.

“Never mind I have it all.” I thought and opening my film magazine, I felt for the capsule of the greatest Albatross photographs ever taken. It was not there; I had forgotten to load the contraption!!

To cover my photographic disgrace I worked up my sketches (I still can't combine the two disciplines and don't even point empty cameras at birds these days) and then took a snooze on the bird's very own rock. As the morning wore o , the day became perfect and the whole panorama of the Forth was the backdrop to a happy group of Albatross watchers, cracking away about old limes and new. A great half-day!

New Forest 28 July, 1963

In these days of literally thousands of birders, mass twitching and up to the minute profit-making grape vines, it must be difficult for anyone to comprehend how secret some birds used to be. Throughout my first 30 years in the field, whispered invitations to share

special events were real privileges and one felt truly honoured when they came.

In my London and St Agnes years, I was eventually awarded two looks at “the New Forest ponies”. Puzzled? Well, what you do not know is that those animals were not in this context small horses, but coded Honey Buzzards. The alias was used by a small group of raptor enthusiasts who have never once sought glory but quietly monitored the fortunes of our rarest breeding raptor for more than 30 years. Incidentally, they have also invented the only technology for making tea safely up trees!

My second visit to “the ponies” was a gem of an experience, with a supporting cast of other wildlife, and great trees that evoked a much older time and land. My notebook records: “At the rendezvous by 0745, quickly found by the Admiral (no names, no pack drill, no disturbed “ponies”) put on the pillion of his 500cc and blasted to the group camp for the first brew of the day.”

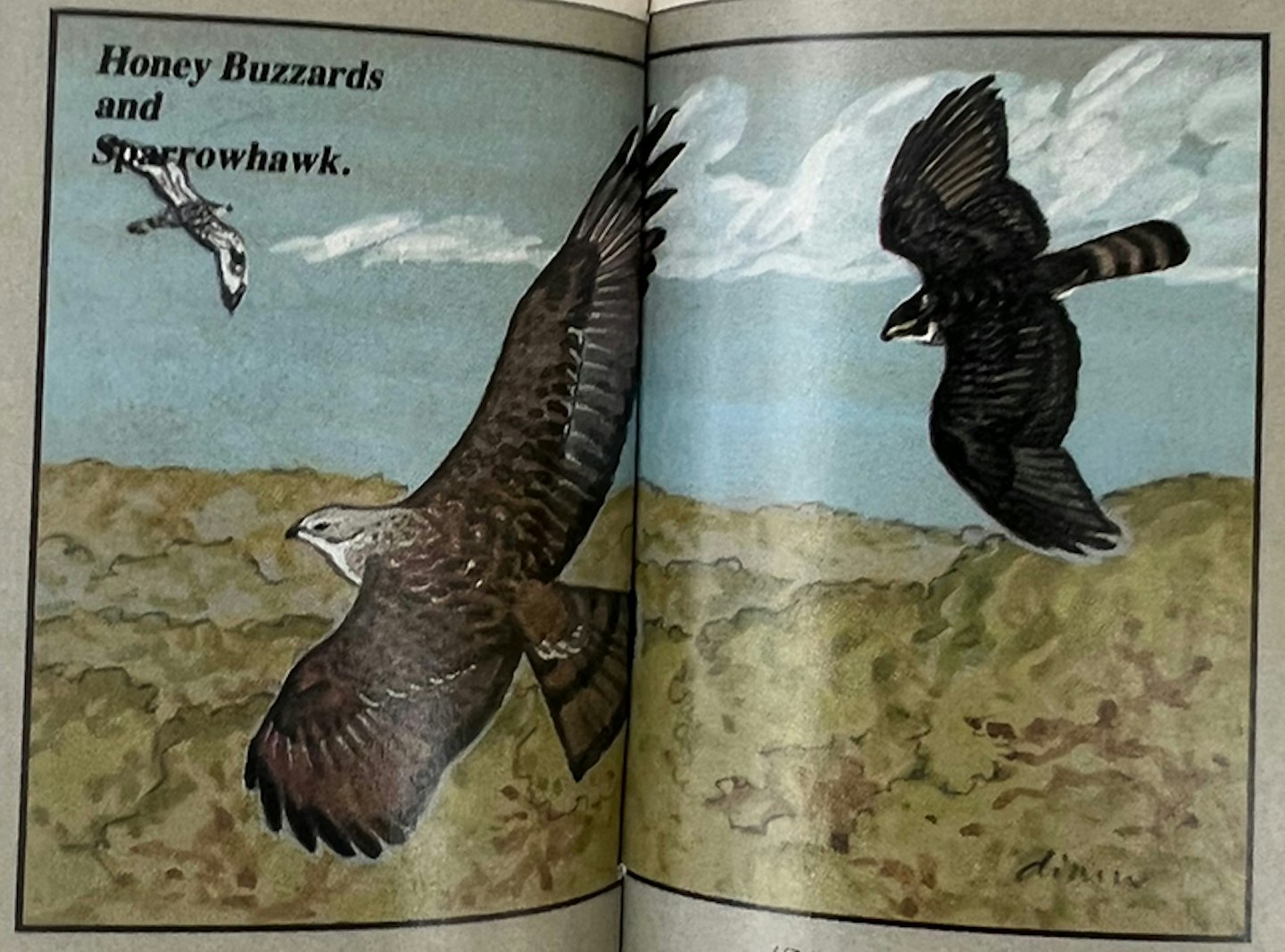

Restored, if not totally tanned internally, we were at the day's designated watchpoint by 0815. With still cool air, little happened for an hour but then with sudden warmth (hence rising air), the first predators of the day came out and up. The first two “broadwings” were plain Buzzards, an Accipiter was a Sparrowhawk but a third big and distance raptor looked odd. The experts conferred for several minutes but the final vote was unanimous and negative – just a young, oddly-plumaged Buzzard. Patient scanning of the northern canopies recommenced.

Eventually, away to the east, a looser-winged, vaguely kite-like and somehow slightly pre-historic raptor blipped. “This could be a pony” snapped the Admiral. The bird came on, drifting over the nearest ridge. Then it tipped down towards the treetops and, with the intricate wing and tail bars of the right pattern well seen, we had a Honey Buzzard for sure.

Out of nowhere appeared a second – in display flight and trailing an irritated Sparrowhawk – and our eyes crossed as we tried to watch for their separate entry points to the canopy. Some confusion ensued but eventually the first folded its wings and shot in directly opposite us. With a clear target, the group stirred only to be faced immediately with a third bird that came out of the same spot to exit east. This had me overwhelmed with “ponies”' and the experts puzzled.

They had been looking for flight angles between food sources (mainly “porridge? code name for larva-full wasp nests) but were having to face the prospect of an instant new nest (and not the patient usual cross-plotting needed to find one).

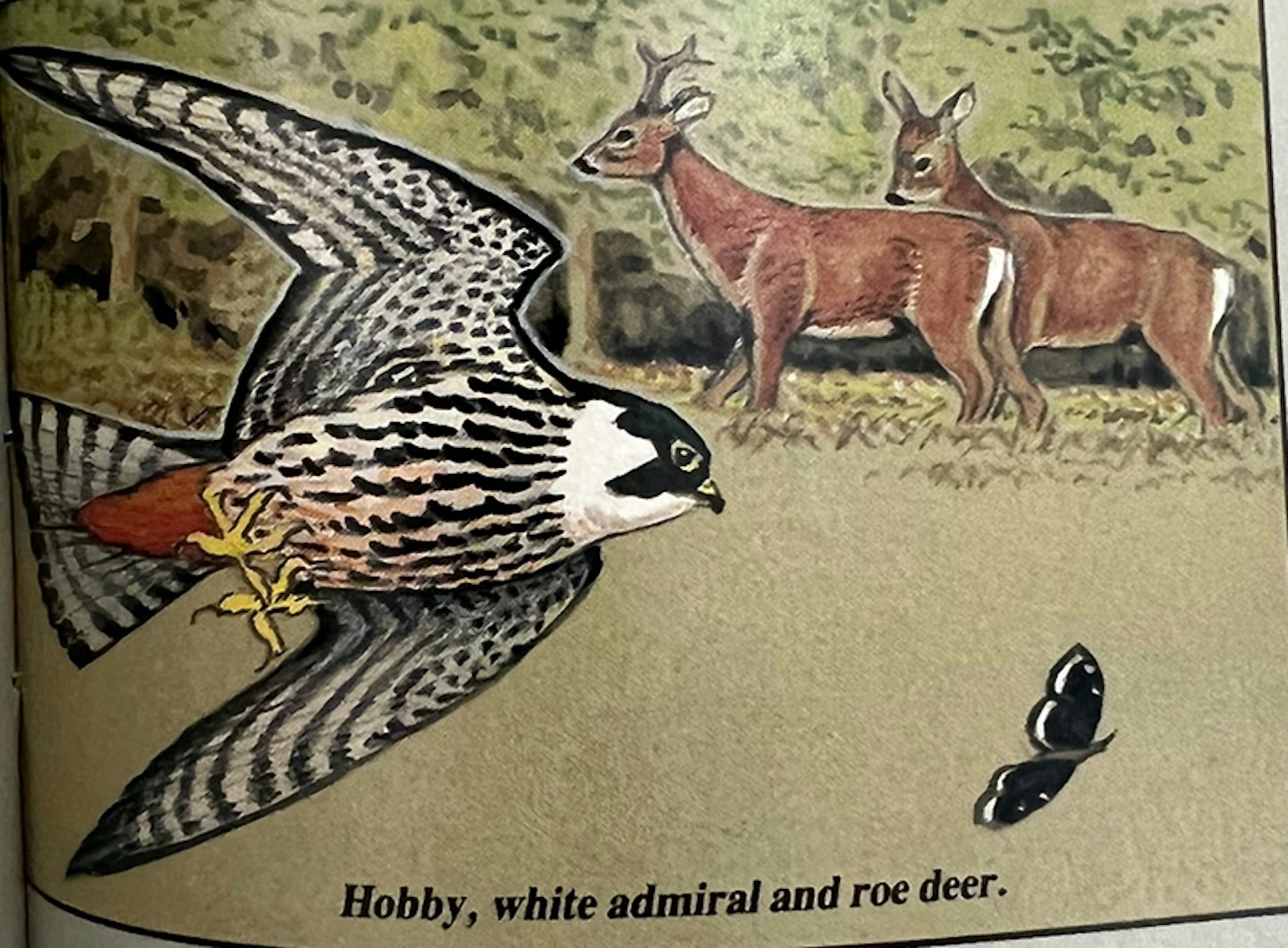

“Leap in,” ordered the Admiral and at a rate exceeding the lightest infantry step, the New Forest HB Commando Unit evaporated into the trees. I scarpered after them, reaching the target ridge in time for yet another “pony” to sweep through the huge old oaks that now surrounded us. With no understanding on nest location, I hung back in a glade and was entranced by the passage of a Fallow doe and fawn and several white admirals (no relation to our leader but a 'lifer' butterfly!). Old England embraced me in a warm green spell. The group assembled, out of nest-finding luck and the Admiral ordered a retreat to avoid further disturbance.

Moving down the ridge, however, another broadwing blip was glimpsed – more a shadow in the leaves than a bird – and then a few yards on we put another certain Honey Buzzard out from the lower plantation. Raised eyebrows were on every face. Had we somehow passed the nest site on our way in? As if to affirm this likelihood, the last bird of at least three (or was it four?) continued to wheel overhead, calling ‘w'lee'a’ loudly and clearly anxious.

The group spread out in a last, fast search; I moved away to savour the forest again, stepping out into a sun-bathed running with a rush-lined stream. Upward of me fed two Roe Deer; over the rushes flew two new species of large dragonfly (still mysteries but one with flashing blue and black wings was unforgettable) and above them scythed a lithe Hobby hunting butterflies. The place's spell moved up a gear to virtual trance as all modern time fell away and I looked upon a cameo not just of England but Ancient Europe.

A quiet footstep behind me turned my head. There was a quietly beaming Admiral. “Come on, Ian; we've found the nest. One look before we leave her in peace”.

We hurried past the broad platform, noting a sprig of fresh leaves (a frequent nest decoration) and climbed back to the camp. As another huge brew was prepared, I checked my watch. What had seemed a small epoch of nature had occupied little over an hour. Noting the seriousness of the experts as they discussed the significance of a new nest site and the need now to protect it, I was afflicted not for the first time with the unease of a birdwatcher who hunts more than he gathers. Surely, the Admiral and his fellows knew one avian being better than any skilled amateur or professional observer in Britain. I had some long way to go to match their application and effort.

The presence of Honey Buzzards in the New Forest and occasionally elsewhere is no longer a state secret, but sadly their numbers have not grown. A few still come in, but they are much more specialised than kites and have to run the gauntlets of a long migratory path. Certainly, they are not for me or you to chase. They need all the peace that is left and probably more. Please.