A new series of DIMW’s birding reminiscences (from BW in 1989)

**School ‘owlers’

**

A copybook exercise in doing the wrong thing

In a new series of personal reminiscences drawn from his 45 years in the field (and counting) – Ian Wallace will take you into the heart of birdwatching. He begins with his first-ever rarity and two puzzling owlets at Aberlady Bay (13 May 1950).

My third ornithological tutor was the senior French master at Loretto School, Musselburgh. He was two teachers in one, incredibly boring as we struggled with grammar and declension, totally invigorating as we progressed to Cyrano de Bergerac and beyond our first certain identification of Dunlin.

That achievement took place on the Musselburgh foreshore, now much changed by reclamation but still producing good birds and with it and other common wader trials behind us, we were at last equipped to tackle the wildfowl battalions of Lothian's two great bird bays, at Aberlady and further east at Tynninghame.

Aberlady Bay was our favourite haunt. located an hour or so from school along an increasingly pleasant coastline given "head down and pedal hard" on our ancient, high-handled bikes. It was further blessed by its position outside the "no ice cream will be eaten during term" zone that surrounded the school. This carried a four stroke beating if encroached upon. No wonder that the bay was our regular Saturday afternoon goal in the Summer term.

Here's my account of that memorable day in 1950:

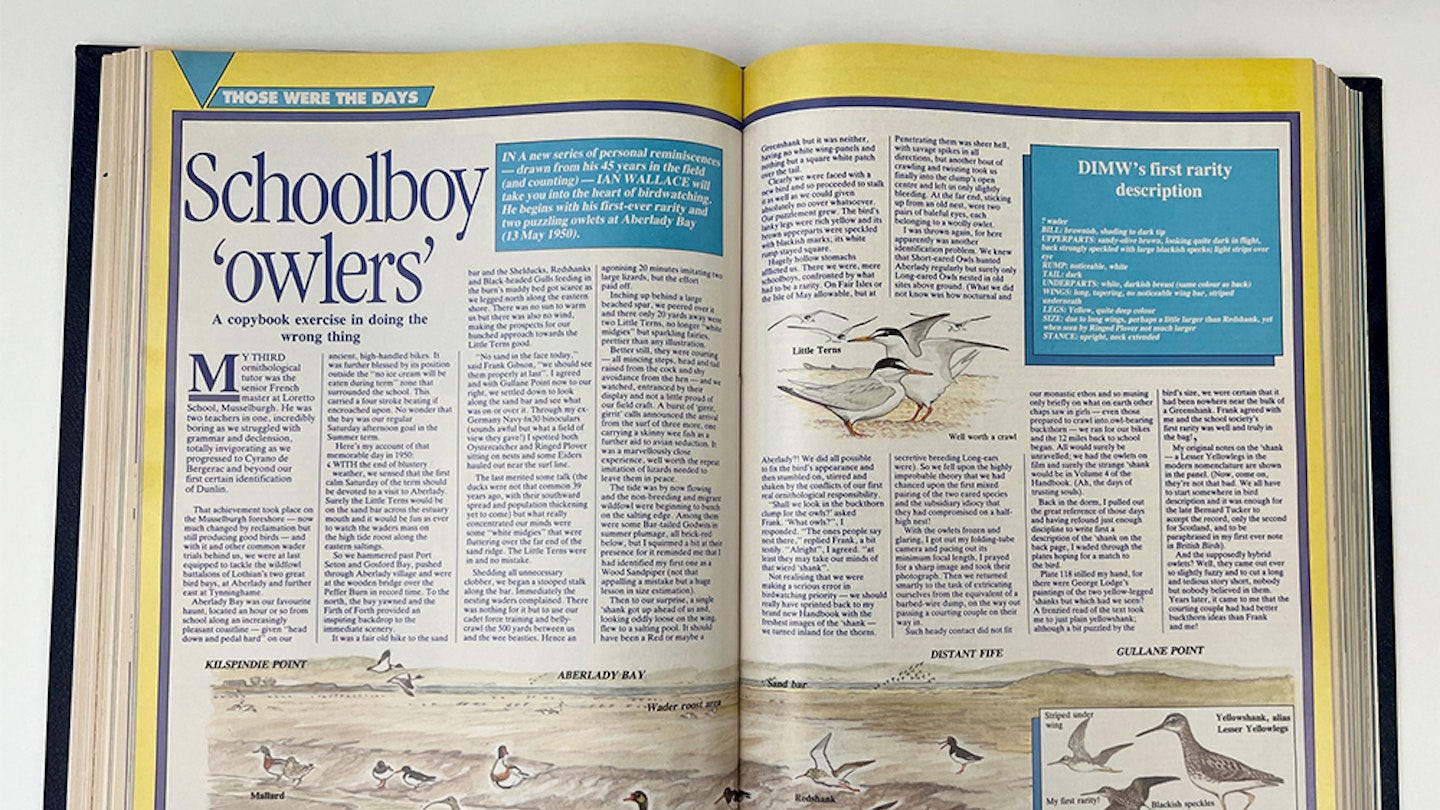

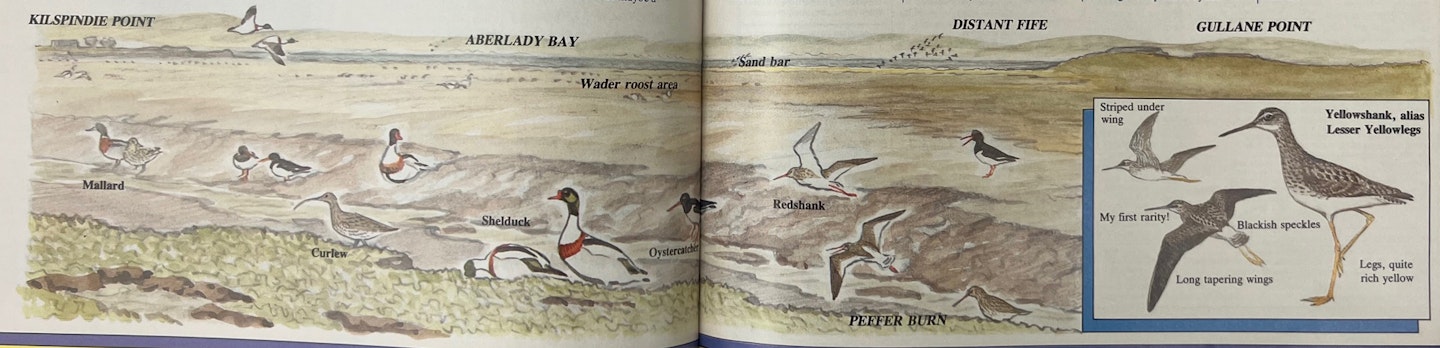

With the end of blustery weather, we sensed that the first calm Saturday of the term should be devoted to a visit to Aberlady. Surely the Little Terns would be on the sand bar across the estuary mouth and it would be fun as ever to watch the waders mass on the high tide roost along the eastern saltings.

So we hammered past Port Seton and Gosford Bay, pushed through Aberlady village and were at the wooden bridge over the Peffer Burn in record time. To the north, the bay yawned and the Firth of Forth provided an inspiring backdrop to the immediate scenery.

It was a fair old hike to the sand bar and the Shelducks, Redshanks and Black-headed Gulls feeding scarce as we legged north along the eastern shore. There was no sun to warm us but there also no wind, making the prospects for our hunched approach the Little Terns good.

"No sand in the face today” said Frank Gibson, “we should see them properly at last”. I agreed and with Gullane Point now to our right, we settled down to look along the sandbar and see what was on or over it. Through my ex-German Navy 6x30 binoculars (sounds awful, but what a field of view they gave!) I spotted both Oysterdatcher and Ringed Plover sitting on nests and some Eiders hauled our near the surf line.

The last merited some talk (the ducks were not that common 39 [sic] years ago, with their southward spread and population thickening yet to come) but what really concentrated our minds were some “white midgies” that were fluttering over the far end of the sand ridge. The Little Terns were in and no mistake.

Shedding all unnecessary clobber, we began a stooped stalk along the bar. Immediately, the nesting waders complained. There was nothing for it but to use our cadet force training and belly crawl the 500 yards between us and the wee beauties. Hence, an agonising 20 minutes imitating two large lizards, but the effort paid off.

Inching up behind a large beached spar, we peered over it and there only 20 yards away were two Little Terns, no longer “white midgies” but sparkling fairies, prettier than any illustrations.

Better still, they were courting – all mimicking steps, head and tailed raised from the cock and shy avoidance from the hen – and we watched, entranced by their display and not a little proud of our field craft. A burst of ‘girrit girrit’ calls announced the arrival from the surfof three more, one carrying a skinny wee fish as a further aid to avian seduction. It was a marvellously close experience, well worth the repeat imitation of lizards needed to leave them in peace.

The tide was by now flowing and the non breeding and migrant wildfowl were beginning to bunch on on the salting edge. Among them were some Bar-tailed Godwitsin summer plumage, all brick-red below, but I squirmed a bit at their presence for it reminded me that I had identified my first one as a Wood Sandpiper (not that appalling a mistake, but a huge lesson in size estimation!)

The to our surprise, a sungle ‘shank’ got up ahead of us and looking oddly loose on the wing, flew to salting pool. It should have been a Redshank or maybe a Greenshank, but it was neither, having no white wing-panels and nothing but a square white patch over the tail.

Clearly we were faced with a new bird and so proceeded to stalk it as well as we could given absolutely no cover whatsoever. Our puzzlement grew. The bird’s lanky legs were rich yellow and its brown upperparts were specked with blackish marks; its white rump stayed square.

Hugley hollow stomachs afflicted us. There we were, mere schoolboys, confronted by what had to be a rarity. On Fair Isle, or the Isle of May allowable, but at Aberlady?! We did all possible to fix the bird's appearance and then stumbled on, stirred and shaken by the conflicts of our first real ornithological responsibility.

"Shall we look in the buckthorn clump for the owls?' asked Frank. “What owls?", I responded. "The ones people say nest there, " replied Frank, a bit testily. "Alright" . I agreed. "at least they may take our minds of that weirrd 'shank’"

Not realising that we were making a serious error in birdwatching priority – we should really have sprinted back to my brand new Handbook with the freshest images of the shank we turned inland for the thorns. Penetrating them was sheer hell, with savage spikes in all directions, but another bout of crawling and twisting took us finally into the clump's open centre and left us only slightly bleeding. At the far end, sticking up from an old nest, were two pairs of baleful eyes, each belonging to a woolly owlet.

I was thrown again, for here apparently was another identification problem. We knew that Short-eared Owls hunted Aberlady regularly but surely only Long-eared Owls nested in old sites above ground. (What we did not know was how nocturnal and secretive breeding Long-eareds were). So we fell upon the highly improbable theory that we had chanced upon the first mixed pairing of the two eared species and the subsidiary idiocy that they had compromised on a half-high nest!

With the owlets frozen and glaring, I got out my folding-tube camera and pacing out its minimum focal length, I prayed for a sharp image and took their photograph. Then we returned smartly to the task of extricating ourselves from the equivalent of a barbed-wire dump, on the way out passing a courting couple on their way in...

Such heady contact did not fit our monastic ethos and so musing only briefly on what on Earth other chaps saw in girls – even those prepared to crawl into owl-bearing buckthorn – we ran for our bikes and the 12 miles back to school began. All would surely be unravelled; we had the owlets on film and surely the strange "shank would be in Volume 4 of the Handbook. (Ah, the days of trusting souls).

Back in the dorm, I pulled out the great reference of those days and having refound just enough discipline to write first a description of the ‘shank’ on the back page, I waded through the plates hoping for a match to the bird.

Plate 118 stilled my hand, for there were George Lodge paintings of the two yellow-legged shanks (ie Yellowlegs) but which had we seen? A frenzied read of the text took me to just plain Yellowshank; although a bit puzzled by the bird's size, we were certain that it had been nowhere near the bulk of a Greenshank. Frank agreed with me and the school society's first rarity was well and truly in the bag!

My original notes on the shank – a Lesser Yellowlegs in the modern nomenclature – are shown in the panel. (Now, come on, they're not that bad. We all have to start somewhere in bird description and it was enough for the late Bernard Tucker to accept the record, only the second for Scotland, and to be paraphrased in my first ever note in British Birds). And the supposedly hybrid owlets? Well, they came out ever so slightly fuzzy and to cut a long and tedious story short, nobody but nobody believed in them. Years later, it came to me that the courting couple had had better buckthorn ideas than Frank and me!

DIMW's first rarity description

? wader

BILL: brownish, shading to dark tip

UPPERPARTS: sandy-olive brown, looking quite dark in flight, back strongly speckled with large blackish specks; light strips over eye

RUMP: noticeable, white

TAIL: dark

UNDERPARTS: white, darkish breast (same colour as back)

WINGS: long, tapering, no noticeable wing bar, striped underneath

LEGS: Yellow, quite deep colour

SIZE: due to long wings, perhaps a little larger than Redshank, yet when seen by Ringed Plover not much larger

STANCE: upright, neck extended