Low-level hunting Circus

February 1989

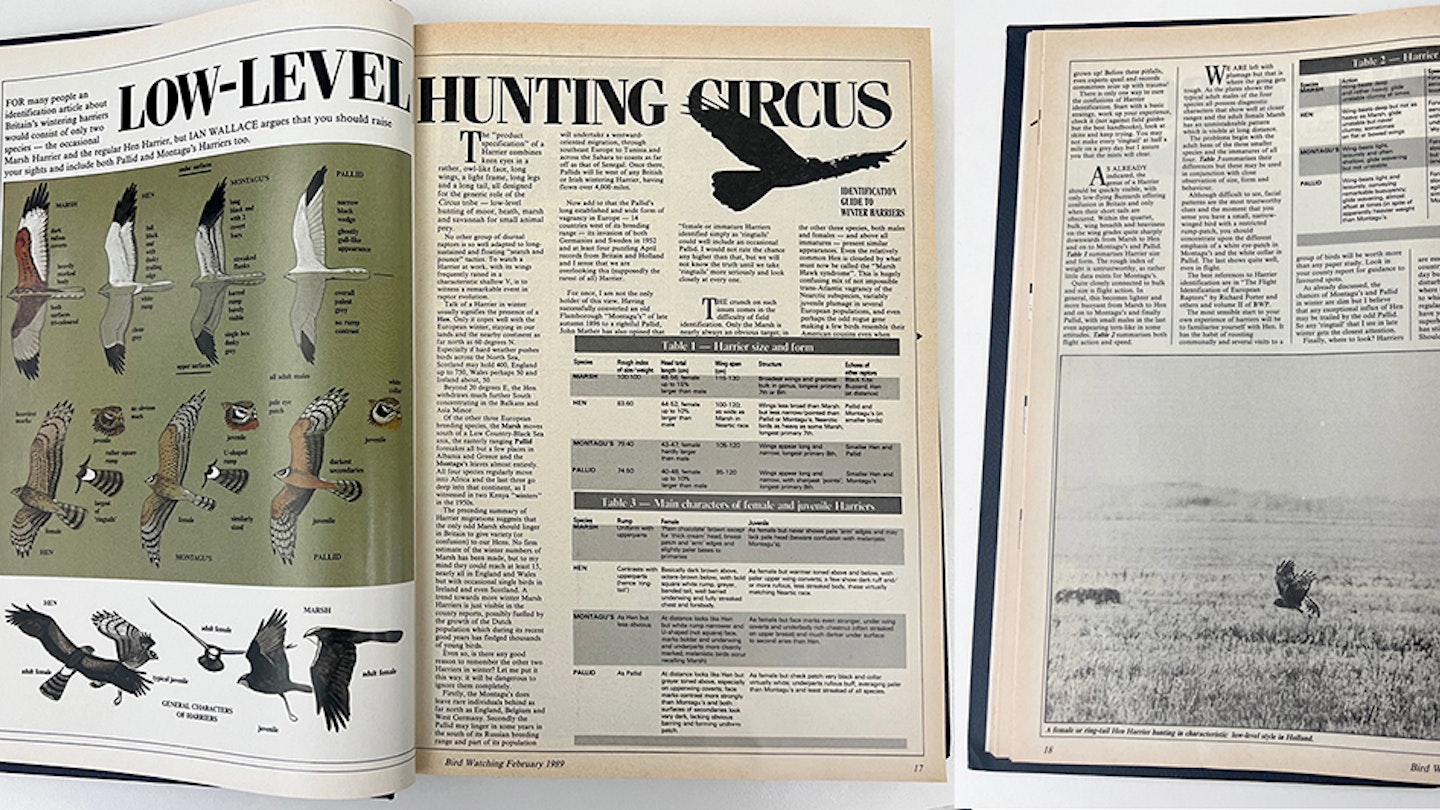

For many people an identification article about Britain's wintering harriers would consist of only two species: the occasional Marsh Harrier and the regular Hen Harrier, but Ian Wallace argues that you should raise your sights and include both Pallid and Montagu's Harriers, too.

The ‘product specification’ of a harrier combines keen eyes in a rather, owl-like face, long wings, a light frame, long legs and a long tail, all designed for the generic role of the Circus tribe, low-level hunting of moor, heath, marsh and savannah for small animal prey.

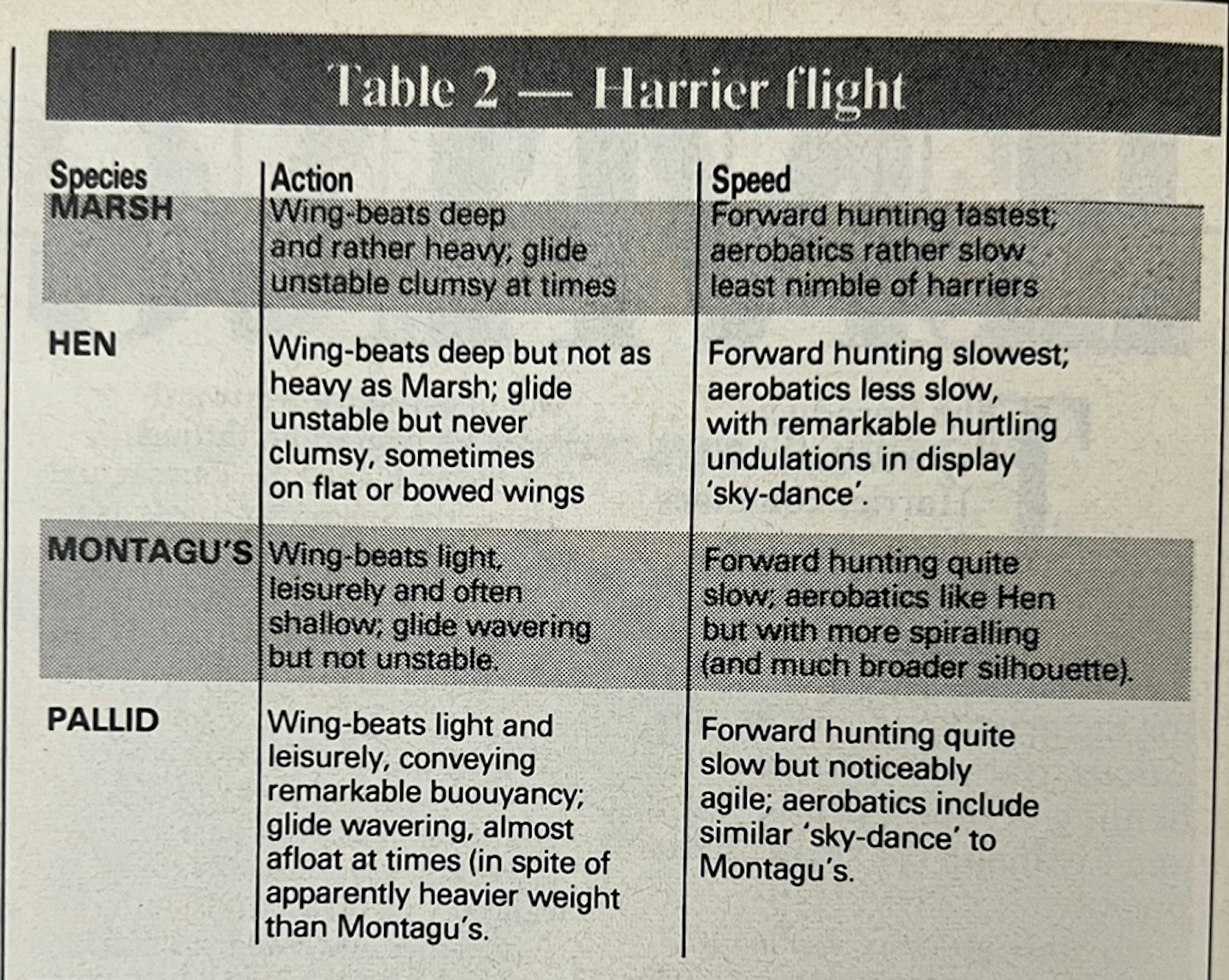

No other group of diurnal raptors is so well adapted to long- sustained and floating ‘search and pounce’ tactics. To watch a Harrier at work, with its wings frequently raised in a characteristic shallow V, is to witness a remarkable event in raptor evolution.

Talk of a harrier in winter usually signifies the presence of a Hen. Only it copes well with the European winter, staying in our lands and the nearby continent as far north as 60°N Especially if hard weather pushes birds across the North Sea, Scotland may hold 400, England up to 750, Wales perhaps 50 and Ireland about, 50.

Beyond 20°E, the Hen withdraws much further South concentrating in the Balkans and Asia Minor.

Of the other three European breeding species, the Marsh moves south of a Low Country-Black Sea axis, the easterly ranging Pallid forsakes all but a few places in Albania and Greece and the Montagu's leaves almost entirely. All four species regularly move into Africa and the last three go deep into that continent, as I witnessed in two Kenya ‘winters’ in the 1950s.

The preceding summary of harrier migrations suggests that the only odd Marsh should linger in Britain to give variety (or confusion) to our Hens. No firm estimate of the winter numbers of Marsh has been made, but to my mind they could reach at least 15, nearly all in England and Wales but with occasional single birds in Ireland and even Scotland. A trend towards more winter Marsh Harriers is just visible in the county reports, possibly fuelled by the growth of the Dutch population which during its recent good years has fledged thousands of young birds.

Even so, is there any good reason to remember the other two Harriers in winter? Let me put it this way: it will be dangerous to ignore them completely.

Firstly, the Montagu's does leave rare individuals behind as far north as England, Belgium an West Germany. Secondly the Pallid may linger in some years in the south of its Russian breeding range and part of its population will undertake a westward-oriented migration, through south-east Europe to Tunisia and across the Sahara to coasts as far off as that of Senegal. Once there, Pallids will lie west of any British or Irish wintering harrier, having flown more than 4,000 miles.

Now add to that the Pallid's long established and wide form of vagrancy in Europe – 14 countries west of its breeding range its invasion of both Germanies and Sweden in 1952 and at least four puzzling April records from Britain and Holland and I sense that we are overlooking this (supposedly the rarest of all) harrier.

For once, I am not the only holder of this view. Having successfully converted an old Flamborough ‘Montagu's’ of late autumn 1896 to a rightful Pallid, John Mather has also opined that female or immature Harriers identified simply as 'ringtails' could well include an occasional Pallid. I would not rate the chance any higher than that, but we will not know the truth until we take ringtails' more seriously and look closely at every one.

The crunch on such issues comes in the difficulty of field identification. Only the Marsh is nearly always an obvious target; in the other three species, both males and females and above all immatures present similar appearances. Even the relatively common Hen is clouded by what must now be called the ‘Marsh Hawk syndrome’. This is hugely confusing mix of not impossible trans-Atlantic vagrancy of the Nearctic subspecies, variably juvenile plumage in several European populations, and even perhaps the odd rogue gene making a few birds resemble their American cousins even when grown up!

Before these pitfalls, even experts quail and records committees seize up with trauma! There is only one way to cure the confusions of harrier identification. Start with a basic strategy, work up your experience, check it (not against field guides but the best handbooks), look at skins and keep trying. You may not make every 'ringtail' at half a mile on a grey day but I assure you that the mists will clear.

As already indicated, the genus of a harrier should be quickly visible, with only low-flying Buzzards offering confusion in Britain and only when their short tails are obscured. Within the quartet, bulk, wing breadth and heaviness on the wing grades quite sharply downwards from Marsh to Hen and on to Montagu's and Pallid.

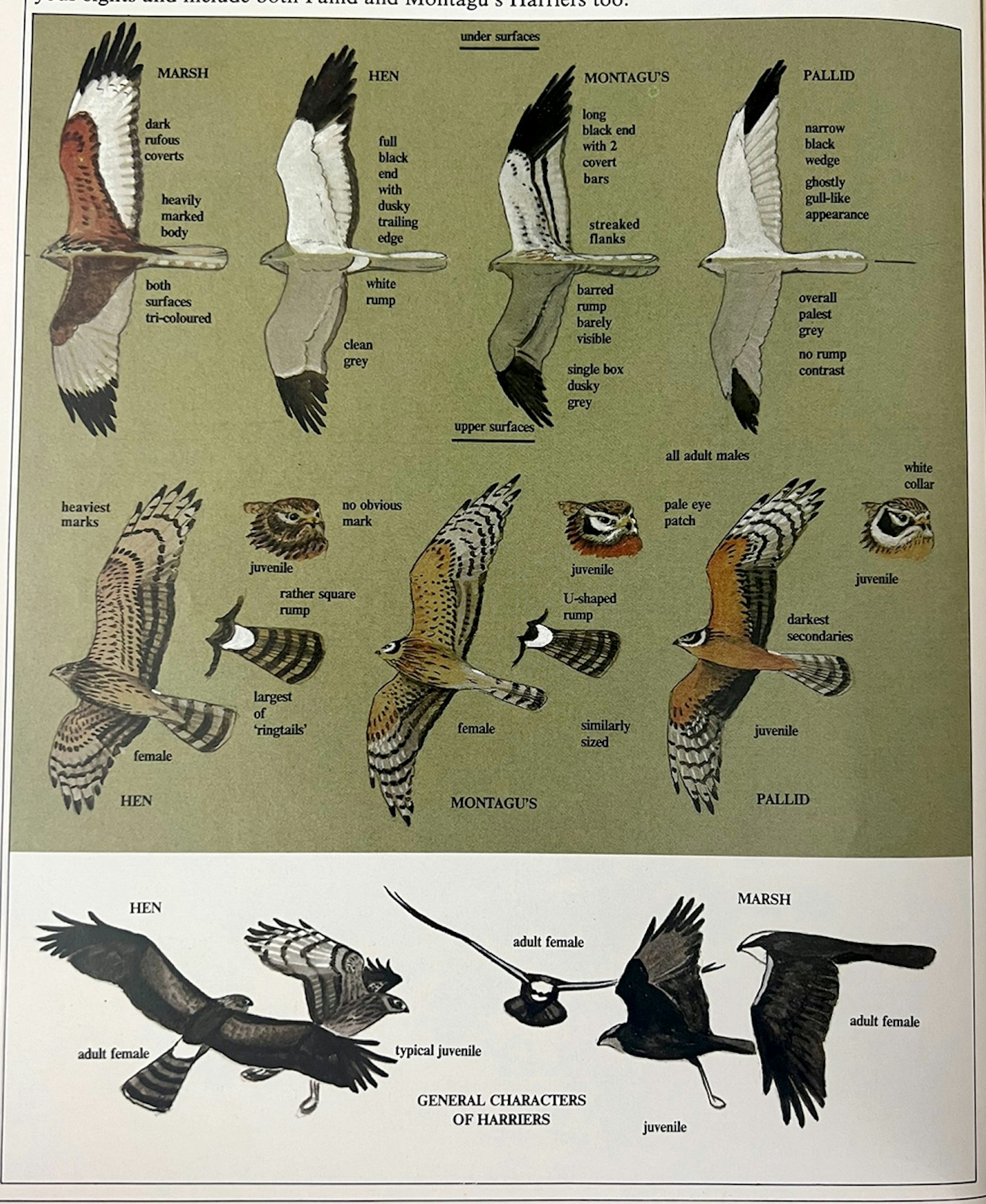

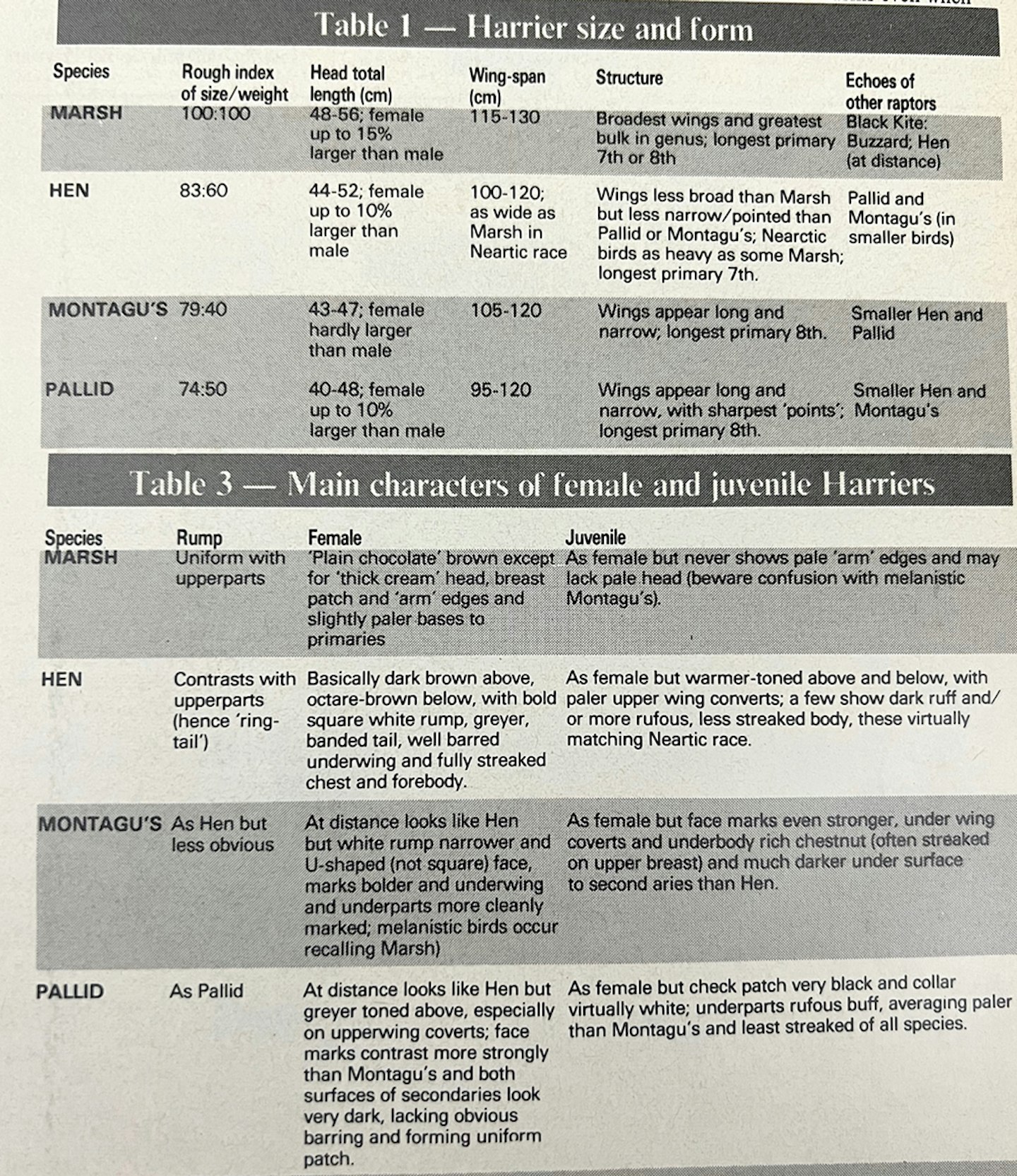

Table 1 summarises Harrier size and form. The rough index of weight is untrustworthy, as rather little data exists for Montagu's. Quite closely connected to bulk and size is flight action. In general, this becomes lighter and more buoyant from Marsh to Hen and on to Montagu's and finally Pallid, with small males in the last even appearing tern-like in some attitudes.

Table 2 summarises both flight action and speed.

We are left with where the going gets tough. As the plates shows the typical adult males of the four species all possess diagnostic characters that show well at closer ranges and the adult female Marsh has an unmistakeable pattern which is visible at long distance. The problems begin with the adult hens of the three smaller species and the immatures of all four. Table 3 summarises their differences but these may be used in conjunction with close observation of size, form and behaviour.

Although difficult to see, facial patterns are the most trustworthy clues and the moment that you sense you have a small, narrow-winged bird with a restricted rump-patch, you should concentrate upon the different emphasis of a white eye-patch in Montagu's and the white collar in Pallid. The last shows quite well, even in flight.

The best references to Harrier identification are in The Flight Identification of European Raptors by Richard Porter and others and volume II of BWP.

The most sensible start to your own experience of harriers will be to familiarise yourself with Hen. It has the habit of roosting communally and several visits to a group of birds will be worth more than any paper study. Look in your county report for guidance to favoured spots.

As already discussed, the chances of Montagu's and Pallid in winter are slim but I believe that any exceptional influx of Hen may be trailed by the odd Pallid. So any 'ringtail' that I see in late winter gets the closest attention.

Finally, where to look? Harriers are essentially birds of open country, wandering widely every day but favouring the least disturbed areas of grass and marsh where their prey is abundant and to which birds may come regularly. It is there that you will have your best chance to tackle a superb group of raptors. Much has still to be learnt about them. Shoulders to the wheel!

2020s update

In the 21st Century Marsh Harriers have become regular wintering birds in the UK. At most sites in the south and east of the country, in particular, Marsh Harriers are now more numerous at winter roosts than Hen Harriers.

Pallid Harriers are now regular (more frequently than annual) visitors in very small numbers to the UK, while Montagu’s Harriers are all but unheard of in winter.

The North American Marsh Hawk or Northern Harrier has also been recorded on a few occasions.