Lapland Wanderers

July 1988

July should mean high summer everywhere in Europe, but the month quickly becomes full of early bird movements. Of these, the most obvious – even inland is the early return of northern waders. Here, Ian Wallace discusses this phenomenon.

In the smaller world of birdwatching that existed in the 1950s, Lapland was one of the few peripheral pieces of Europe that was regularly visited by British observers. The mix of northern taiga, tundra and ultimate coasts sparkled with truly northern species and they were our first targets after a ‘decent grip’ of the commoner British birds (250 was then a good score!) Nobody even thought of Bee-eaters in Spain – ‘southern rubbish', we sneered.

For me, the desire to watch winter visitors and passage migrants on their breeding grounds was fulfilled in June and July 1957. Equipped with youthful energy and one of the original black Morris Minors, Joe Cunningham, Peter Naylor and I observed the then statutory discipline of the Cambridge Bird Club and drove virtually non-stop from the docks at Gothenburg to the signpost of the Arctic Circle. There the traditions of the CBC (and the Scottish Ornithologists' Club) allowed their members to stop, buy the coveted Polar Bear car badge (mine long since stolen!), drink some appalling Finnish pils, observe the non-setting, circling sun and start dodging the mosquitoes. The last trick learnt (or assisted by bee veil over Stetson in my case), we were free to plunge into the birds.

Unfortunately, 1957 was not a ‘lemming year’ and so raptors and skuas were few. We did pretty well with passerines, however, and quite marvellously with waders which were everywhere in bogs, and river shallows around lakes and along shores.

What puzzled us about them were the variations in their breeding behaviour. Plovers were still displaying, Calidris waders were on eggs or had chicks; Snipe and Broad-bills were ‘scraping’ and one Green Sandpiper came off an old nest. In contrast, Wood Sandpipers seemed just nervous, ‘shanks’ were hardly settled and Whimbrels and Bar-tailed Godwits were still strung along shores. We never did unravel this lack of breeding synchronisation but at least it provided a clue to one of the oddities of the British Summer – the tendency of northern waders to start ‘coming back’ almost before completing their ‘going away’!

The phenomenon of the early return of waders can actually be seen first in the June ‘nestings’ of Lapwings but it is most obvious in July when many more species than Lapwing wander. Their arrivals are easiest seen at places of congregation, for example estuary roosts or large reservoirs, but I have also traced them nearly every year at farmland pools and dykes in Cambridgeshire, Gloucestershire, Staffordshire and east Yorkshire – and heard the calls of their participants from night skies in these more inland counties and the very heart of London.

So no birdwatcher with the legs for cross-country exploration need miss out on Lapland wanderers. They can turn up in the most surprising habitats, including in my experience fog-bound airport runways (Little Stint), soggy mounds of soiled straw (Green Sandpiper), cattle-tramped field sumps (Ruff) and park lakes (Sandpipers). They also appear in all sorts of weather, though most of my finds have come during or after heavy rain.

Which are the target species and populations? I am not sure that any scientific analysis has been done but I suspect that they are those that:

(1) find within their total range some Arctic conditions not suited to their breeding needs and therefore depart frustrated.

(2) are not sufficiently fit enough to breed in a particular summer and may well perform incomplete migrations.

(3) are not sexually mature and simply go through some partial motions.

Together these classes could constitute an annual surplus to the breeding masses which does little more than fidget (biologically) and soon settles for withdrawal back towards the less stressful life available in staging areas and winter grounds.

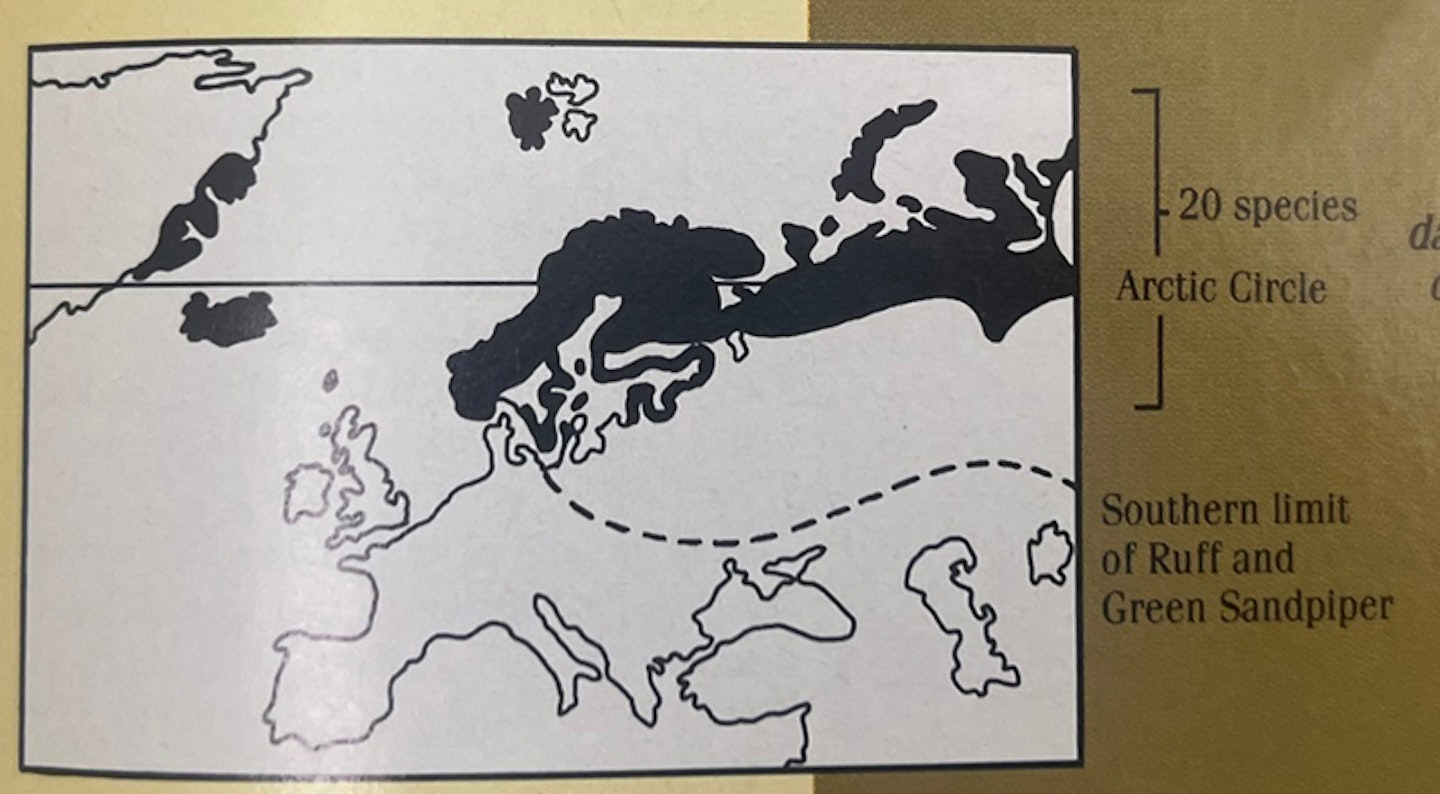

Because of some wide longitudinal ranges (and some species' southern races), it is difficult to define the July list of itinerant Lapland and arctic waders precisely, but the following are pretty certain: Oystercatcher, Grey Plover, northern Golden Plover, Whimbrel, Bar-tailed Godwit, Spotted Redshank, Continental Redshank, Greenshank, Green Sandpiper, Wood Sandpiper, Common Sandpiper, Turnstone, Knot, Sanderling, Little and Temminck's Stints, Purple Sandpiper, Northern Dunlin, Curlew Sandpiper, Ruff.

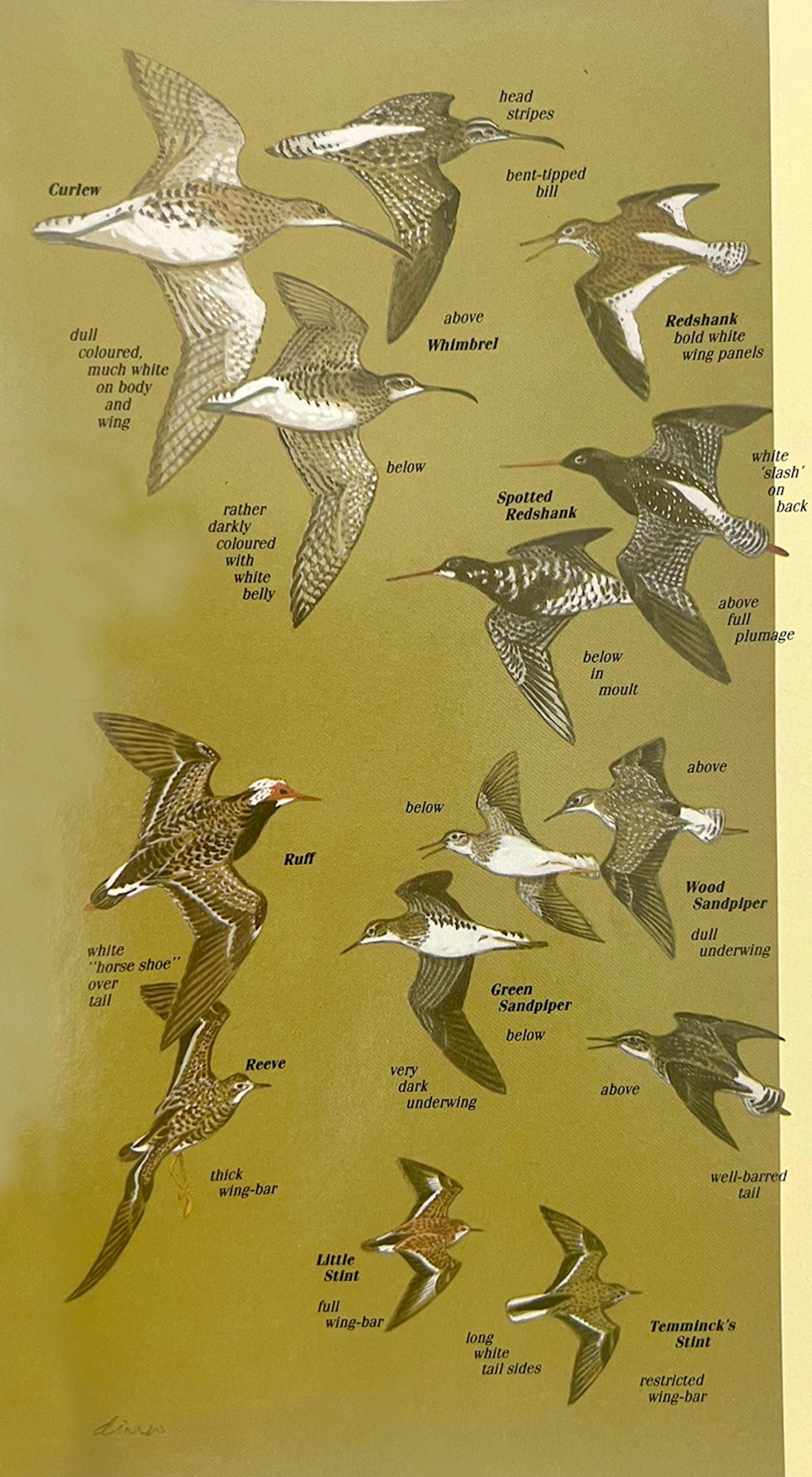

From this score, I have selected seven for fuller identification notes and flight illustration. All occur inland and only a little effort should get you started with the most ubiquitous – the splendid Green Sandpiper. Its dark, white-rumped, loose-winged form can rise from waters as small as puddles and its yelled but musical call always catches the ear. In fact, all seven have distinctive combinations of character, plumage and voice and cameos of these follow:

Whimbrel – recalls Curlew but noticeably smaller, with quicker, less gull-like flight action and nimbler gait; usually heard before seen, a function of its far – carrying titter or ‘seven-whistle’: sometimes so high as to escape sight; on the ground, its dark, ‘barred’ flanks, head stripes and more-bent-than-decurved bill provide trustworthy differences from its gawky, rather amorphous cousin; as likely to be heard at night as encountered in daylight but lands in heavy rain.

Spotted Redshank – he shank of shanks, somewhat larger, more attenuated, more graceful and aristocratic than Redshank; not very vocal when wandering but its incisive disyllable is sharper than Redshank, written 'Ki-veet' to ‘tch-it'; flight form slim, with feet trailing (sometimes not, beware confusion with dowitcher!), and action easy, occasionally clipped; long-billed and legged, entering deeper water than Redshank; in summer plumage, black at any distance, more dusky (and pale-flecked spotted) close to, with slash of white between wings; fond of washes and flooded meadows.

Green Sandpiper – suggests, a small, short-legged shank as much as other small sandpiper; secretive, always in ‘bottom waters’, like quiet pools, deep ditches and hidden river shallows; usually encountered ‘bursting out’ of such places, with rapid, erratic flight prolonger into ‘tower’ escape often long, with bird eventually plummeting down into next safe spot; looks very dark olive or black at any distance, with only white rump winking (as on petrels or House Martin); close to, adult shows strong spotting above, bold eye – ring and heavily barred tail; calls freely and loudly, with usually a long phrase like ‘weet-loo-ecit-a-weet-weet-weet’; remarkably ubiquitous, arriving on fronts and particularly after rain.

Wood Sandpiper – smaller, flimsier and more graceful Than Green, with longer, yellowish legs (beware getting twitchy and thinking of Lesser Yellowlegs); nervous, flushing and rising quietly but rarely ‘exiting’ as far as Green; usually found at waters and marshes with wider horizons; at close range, adult speckled. Lacks Green Sandpiper's dark underwing and vivid white rump, due to weaker contrasts; flight action less powerful and calls thinner and dryer, written from ‘chiff-chiff-chiff' to ‘wit-wit-wit'; not as widespread nor as secretive as Green; sometimes with it in river shallows but usually with ‘shanks’.

Little Stint – tiny compared even with Dunlin, compactly and lightly built; lacking loud calls, usually seen first on softest mud of large water but occasionally on floods; upperparts, face and chest of summer adult fox-coloured in sun – light, contrasting with shining white body; legs dark; flight pattern as Dunlin, with grey-sided tail; flight action very fast, yielding remarkable manoeuvrability; usually tame, with short, low escape flight; calls 'tit' or 'tit-tit', more sharply in alarm.

Temminck's Stint – Longer-winged than Little, seeming to stand lower in most attitudes; voice also rather quiet but yells spluttered trill when flushed, developing escape into ‘tower’; unlike Little, secretive (in Europe), haunting small waters with closed horizons, thus liable to be ‘stepped on’; upperparts of adult not dull in summer, with many bright feathers (but these produce patchy, not evenly scaled pattern); chest sides always dusky, much more clouded than Little; contrast between seemingly long dark rump and tail centre and white ramp sides and outer-tail feathers vivid, catching the eye and being totally diagnostic; legs pale.

Ruff – the autumn enigma for wader beginners but far less puzzling in breeding plumage when differences from other medium-sized waders and between large, ruffed male and small, non – ruffed female (Reeve) most obvious; at distance, dark male can suggest spotted Redshank and female Redshank but all Ruffs present slightly clumsy, more shambling and primeval appearance and short-bill; ruff colours highly variable, patterns of other coloured feathers less so but all birds sealed on back and show pale legs; ‘white horseshoe’ mark set low over tail shows well in flight, whose action lacks dash of most waders, giving rather lethargic appearance to flying bird; usually silent; widespread in land, even occurring on open fields where it joins early Lapwing and Golden Plover flocks.

I have never seen all seven during any one July but each time that I find even just one, I am back in the ‘far north’' instantly. Happy hunting for the Lapland wanderers!