Northern majesties

April 1988

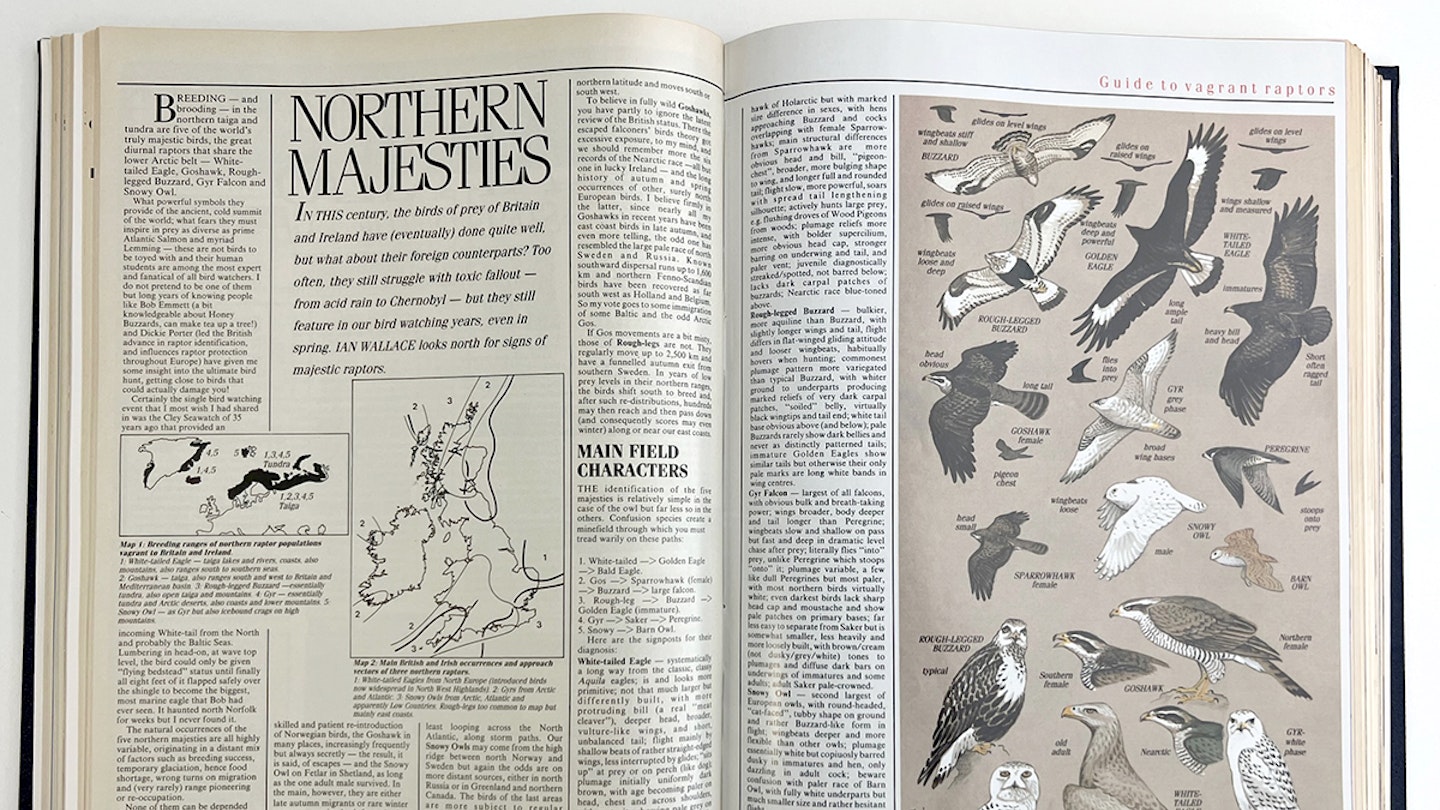

In the 20th Century, the birds of prey of Britain and Ireland have (eventually) done quite well, but what about their foreign counterparts? Too often, they still struggle with toxic fallout from acid rain to Chernobyl – but they still feature in our birdwatching years, even in spring. Ian Wallace looks north for signs of majestic raptors.

Breeding – and brooding – in the northern taiga and tundra are five of the world's truly majestic birds, the great diurnal raptors that share the lower Arctic belt: White-tailed Eagle, Goshawk, Rough-legged Buzzard, Gyr Falcon and Snowy Owl.

What powerful symbols they provide of the ancient, cold summit of the world; what fears they must inspire in prey as diverse as prime Atlantic Salmon and myriad lemming – these are not birds to be toyed with and their human students are among the most expert and fanatical of all birdwatchers. I do not pretend to be one of them, but long years of knowing people like Bob Emmett (a bit knowledgeable about Honey Buzzards, can make tea up a tree!) and Dickie Porter (led the British advance in raptor identification, and influences raptor protection throughout Europe) have given me some insight into the ultimate bird hunt, getting close to birds that could actually damage you!

Certainly, the single birdwatching event that I most wish I had shared in was the Cley seawatch of 35 years ago that provided an incoming White-tail from the North and probably the Baltic Seas. Lumbering in head-on, at wave top level, the bird could only be given ‘flying bedstead’ status until finally all eight feet of it flapped safely over the shingle to become the biggest, most marine eagle that Bob had ever seen. It haunted north Norfolk for weeks but I never found it.

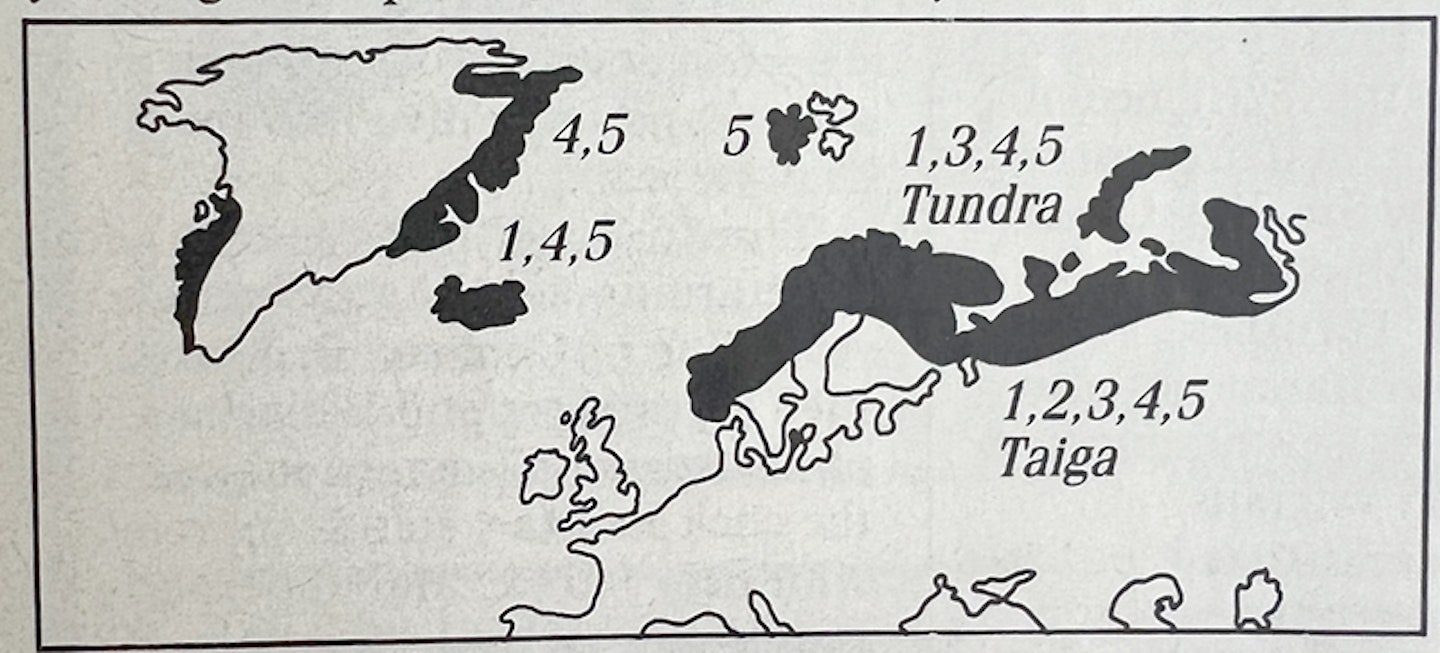

The natural occurrences of the five northern majesties are all highly variable, originating in a distant mix of factors such as breeding success, temporary glaciation, hence food shortage, wrong turns on migration and (very rarely) range pioneering or re-occupation.

None of them can be depended upon, but in the fickle interface of winter and spring, the furthest and most southern vagrants in any dispersal move back. It is then that, historically speaking, many records of them have been made. So don't think that they are unavailable outside a winter blizzard.

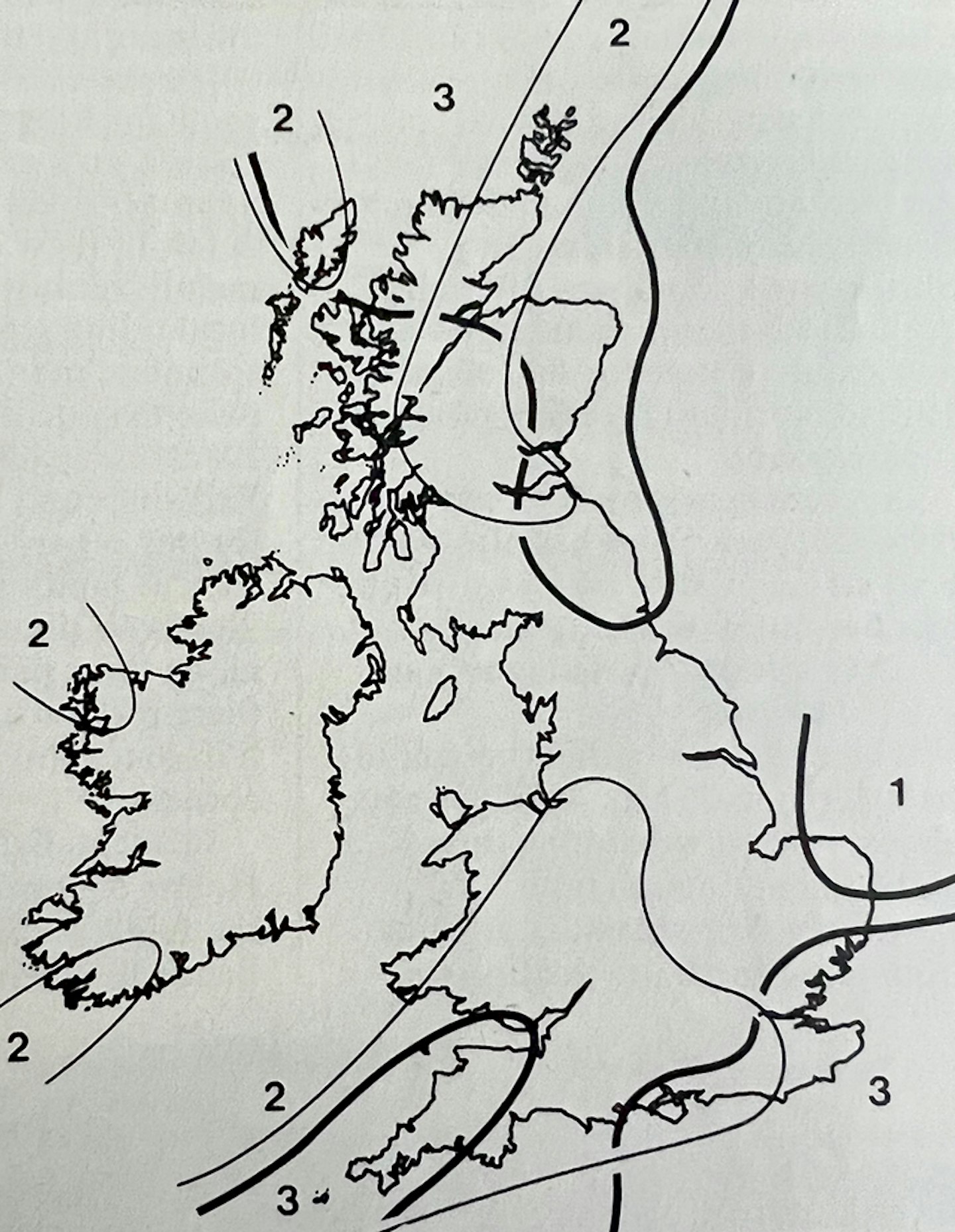

Three members of the quintet have bred recently – the White-tail in north-west Scotland, following a skilled and patient re-introduction of Norwegian birds, the Goshawk in many places, increasingly frequently but always secretly – the result, it is said, of escapes [and releases] – and the Snowy Owl on Fetlar in Shetland, as long as the one adult male survived.

In the main, however, they are either late autumn migrants or rare winter vagrants, coming both from the far north west and the far north east and crossing both Atlantic Ocean and North Sea to reach our lands. Just a bit bigger than of, say, a Two-barred Greenish Warbler!

Origins

Almost all our Gyrs come from Greenland, perhaps using the using Iceland-Faeroes route but some at least looping across the North Atlantic, along storm paths.

Our Snowy Owls may come from the high ridge between north Norway and Sweden but again the odds are on more distant sources, either in north Russia or in Greenland and northern Canada. The birds of the last areas are more subject to regular migrations and pronounced eruptions than their Palearctic relatives.

The origins of wild White-tailed Eagles are less easy to work out. The odds on Icelandic and Norwegian birds are not high their prey is not frozen over in winter – and our vagrants are much more likely to come from Finland or Russia, where the species regularly leaves 15° of northern latitude and moves south or south-west.

To believe in fully wild Goshawks, you have partly to ignore the latest review of the British status. There, the escaped falconers' birds theory got excessive exposure, to my mind, and we should remember more the six records of the Nearctic race – all but one in lucky Ireland – and the long history of autumn and spring occurrences of other, surely north European birds. I believe firmly in the latter, since nearly all my Goshawks in recent years have been east coast birds in late autumn, and even more telling, the odd one has resembled the large pale race of north Sweden and Russia. Known southward dispersal runs up to 1,600 km and northern Fenno-Scandian birds have been recovered as far south west as Holland and Belgium. So my vote goes to some immigration of some Baltic and the odd Arctic Gos.

If Gos movements are a bit misty, those of Rough-legs are not. They regularly move up to 2,500 km and have a funnelled autumn exit from southern Sweden. In years of low prey levels in their northern ranges, the birds shift south to breed and, after such re-distributions, hundreds may then reach and then pass down (and consequently scores may even winter) along or near our east coasts.

Main field characters

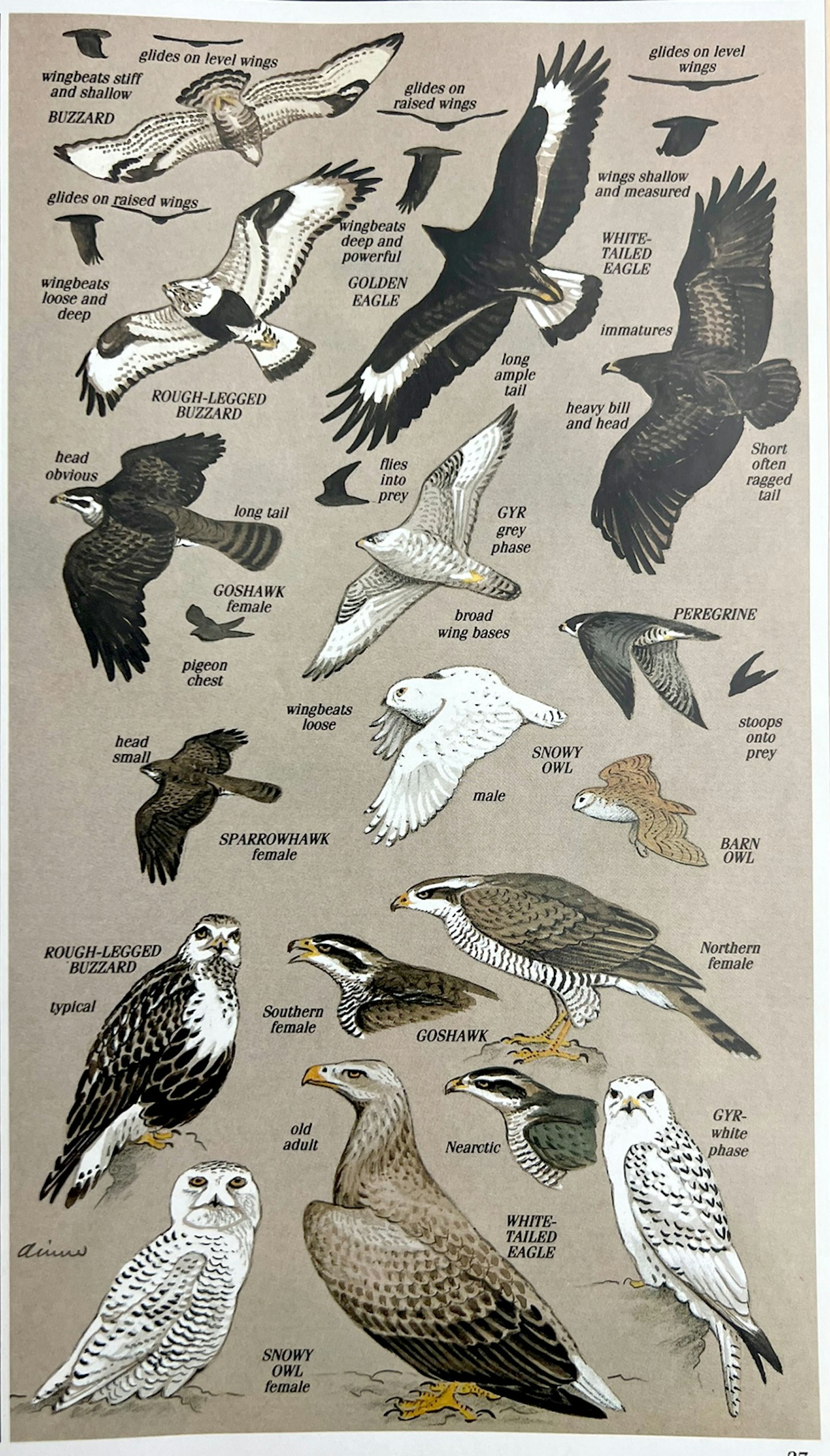

The identification of the five majesties is relatively simple in the case of the owl but far less so in the others. Confusion species create a minefield through which you must tread warily on these paths:

1. White-tailed > Golden Eagle > Bald Eagle.

2. Gos > Sparrowhawk (female) > Buzzard > large falcon.

3. Rough-leg > Buzzard Golden Eagle (immature).

4. Gyr > Saker > Peregrine.

5. Snowy > Barn Owl.

Here are the signposts for their diagnosis:

White-tailed Eagle

Systematically a long way from the classic, classy Aquila eagles; is and looks more primitive; not that much larger but differently built, with more protruding bill (a real ‘meat cleaver’), deeper head, broader, vulture-like wings, and short, unbalanced tail; flight mainly by shallow beats of rather straight-edged wings, less interrupted by glides; ‘sits up’ at prey or on perch (like dog); plumage initially uniformly dark brown, with age becoming paler on head, chest and across shoulders, with maturity showing pale grey on head and white on tail; bill initially dusky, eventually pale yellow; always lacks golden mane and wing patches of Golden (but remember it shows white tail base when young); congener of Bald – now once again suspected of crossing Atlantic – and far less easy to distinguish as immature (see your American field guide or, safer, handbook).

Goshawk

The largest broadwinged hawk of Holarctic but with marked size difference in sexes, with hens approaching Buzzard and cocks overlapping with female Sparrowhawks; main structural differences from Sparrowhawk are more obvious head and bill, ‘pigeon-chest’, broader, more bulging shape to wing, and longer full and rounded tail; flight slow, more powerful, soars with spread tail lengthening silhouette; actively hunts large prey, e.g. flushing droves of Wood Pigeons from woods; plumage reliefs more intense, with bolder supercilium, paler vent; juvenile diagnostically streaked/spotted, not barred below: lacks dark carpal patches of buzzards; Nearctic race blue-toned above.

Rough-legged Buzzard

Bulkier, more aquiline than Buzzard, with slightly longer wings and tail, flight differs in flat-winged gliding attitude and looser wingbeats, habitually hovers when hunting; commonest plumage pattern more variegated than typical Buzzard, with whiter ground to underparts producing marked reliefs of very dark carpal ‘soiled’ patch wingtips and talfend, white tal belly; virtually base obvious above (and below); pale Buzzards rarely show dark bellies and never as distinctly patterned tails; immature Golden Eagles show similar tails but otherwise their only pale marks are long white bands in wing centres.

Gyr Falcon

The largest of all falcons, with obvious bulk and breath-taking power; wings broader, body deeper and tail longer than Peregrine; wingbeats slow and shallow on pass but fast and deep in dramatic level chase after prey; literally flies ‘into’ prey, unlike Peregrine which stoops ‘onto’ it; plumage variable, a few like dull Peregrines but most paler, with most northern birds virtually white; even darkest birds lack sharp head cap and moustache and show pale patches on primary bases; far less easy to separate from Saker but is somewhat smaller, less heavily and more loosely built, with brown/cream (not dusky/grey/white) tones tO plumages and diffuse dark bars on underwings of immatures and some adults; adult Saker pale-crowned.

Snowy Owl

The second largest of European owls, with round-headed, ‘cat-faced’ , tubby shape on ground and rather Buzzard-like form in flight; wingbeats deeper and more flexible than other owls; plumage essentially white but copiously barred dusky in immatures and hen, only dazzling in adult cock; beware confusion with paler race of Barn Owl, with fully white underparts but much smaller size and rather hesitant flight. None of the above descriptions are complete. For further study, I recommend Birds of the Western Palearctic Volume 2 and the first of the modern ‘monographs’ of field identification, Richard Porter and others' Flight Identification of European Raptors. I have to say that no ordinary field guide is adequate for the vagaries of birds of prey diagnosis.

2020s update

The main changes in recent year are the successful of expansion of White-tailed Eagle as a breeding bird in various parts of Scotland (though mainly still the Inner Hebrides), and the added excitement of young birds released on the Isle of Wight roaming he country.

Also, Snowy owls no longer breed, though with a few resident birds in Scotland, there is always a possible of a return to small breeding populations in the future.