Magnificent Seven

January 1988

There are some sparkling winter passerines to be hunted and enjoyed. Here IAN WALLACE discusses three species and four sub-species of exceptional quality.

One of the best pre-war bird artists was Talbot Kelly, and the painting of his that set me most afire displayed a superb Great Grey Shrike perched over an impaled Goldcrest. How I longed to see a live "Shrike of Shrikes”.

My first visits to North Norfolk came and went without one; trips to observatories produced not a sniff. Then one sparkling winter day in 1952, while bicycling up a north Herts hill, I looked up and there on a pylon wire, set against a pure blue sky, was the great, grey-white, black-splashed terrorist of small birds and beasties.

My bike crashed into the ditch and I dropped my binoculars; the shrike looked down and (I swear) sneered at me. Recovering some control, I got behind the roadside hedge and then enjoyed one of my best half-hours of birdwatching, as the bird dived into a small marshy thicket and scared the proverbial out of several passerine species, eventually knocking down a Blue Tit.

Most of the Great Grey Shrikes that visit us come from north-west Europe, and that area delivers two other peerless passerines to cheer up our winter birdwatching.

One I saw first as long ago as November 1949, in the days when my boarding school regime sent me on compulsory Sunday afternoon walks dressed in best bib, kilt and tucker but no binoculars allowed. One designated route skirted the North Esk River in Mid Lothian and on a hawthorn clump near one bend, I spotted some dumpling-like birds with crests and jewels in their wings.

"They have to be Waxwings”, I exclaimed to my companions, and throwing school rules to the wind I took off at speed for my ex-German Navy 6×30 glasses. Twenty minutes later, my sweaty adoration of the birds confirmed their identity.

From even more northern habitat – the tundra in fact – comes another exceptional bird, with a highly individual personality, and that is the Shore Lark. Not for it the repetition of the “small brown job” plumage of other larks. It dresses in the style of a real aristocrat.

January 1956 produced my first, jostling group in a Cley field. With not one other birdwatcher in sight (can you believe that?!), I got so close that I could even see the short winter “horns” of the males.

Since then I have seen plenty more across North America and in Fenno- Scandia, but I still like them best on a British isle or coast and particularly in late winter and early spring, when song and display often break out in late-staying flocks.

The last four places in my winter star collection go to sub-species. These are not everybody's cup of Tea – no “tick” for a start – but having been over-lectured to ignore them, I have always done the opposite. Having filed away a sizable collection of field descriptions, their conformity is sufficient to demonstrate viable identities.

My favourite is the Northern Treecreeper, which I have seen quite frequently on the East coast and one, tail-less, on St. Martins, Scilly. If the British race is a will of the wisp, the Northern bird qualifies as a real ghost. The best marked are really distinctive.

Two more sub-species that rub shoulders with the Northern Treecreeper in its home range are worth always open eyes. They are the noticeably “macho” Northern Bullfinch. a race with actually long-established occurrences, and the frosty-looking Northern Willow Tit – a sub-species known for 80 years, but only now beginning to get proper attention.

Finally, and as much a change in passerines as you can see, there is the splendidly dark Black-bellied Dipper.

WINTER BEHAVIOUR

In spite of its striking plumage, the Shore Lark is an unobtrusive bird, spending much time quietly walking and running in close searches of ground food sources. Flocks show a characteristic “rolling over” progress and, carefully approached, their members are quite tame. The birds are only noisy when excited.

The Waxwing is not strikingly coloured at any distance, but its tameness – and habit of openly stripping berried branches – make it a frequently obvious target.

The Black-bellied Dipper is secretive, quietly haunting hidden water stretches. Its behaviour is identical to our own bird. Likewise, the Northern Willow Tit and Northern Treecreeper.

Typically, the Great Grey Shrike is the most extrovert of the seven winter stars. Its commonest guise is that of bold sentinel, with its menace constantly emphasised by tail twitching. Its hunting tactic is essentially “sit-wait-spot-pounce-eat or store food”, and it can see voles at 250m! Some birds appear to specialise in sitting among tree canopies, so do not think that they only hunt heaths.

The Northern Bullfinch is far shyer than our own bird, travelling within hedges and haunting thicket centres, but it will tolerate a careful approach and you will need to achieve a close one to be sure of its characters, as with the other three races.

FIELD CHARACTERS AND CALLS

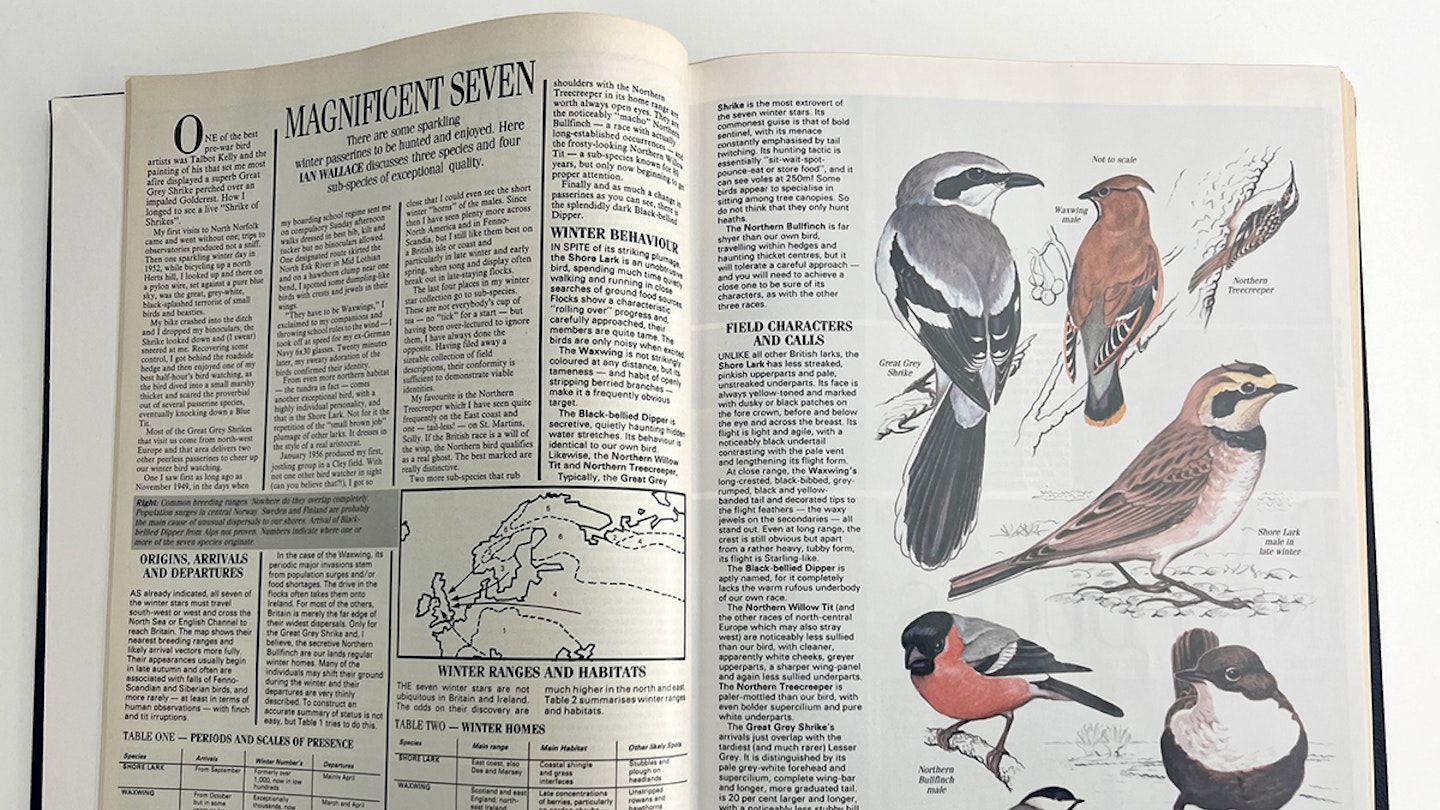

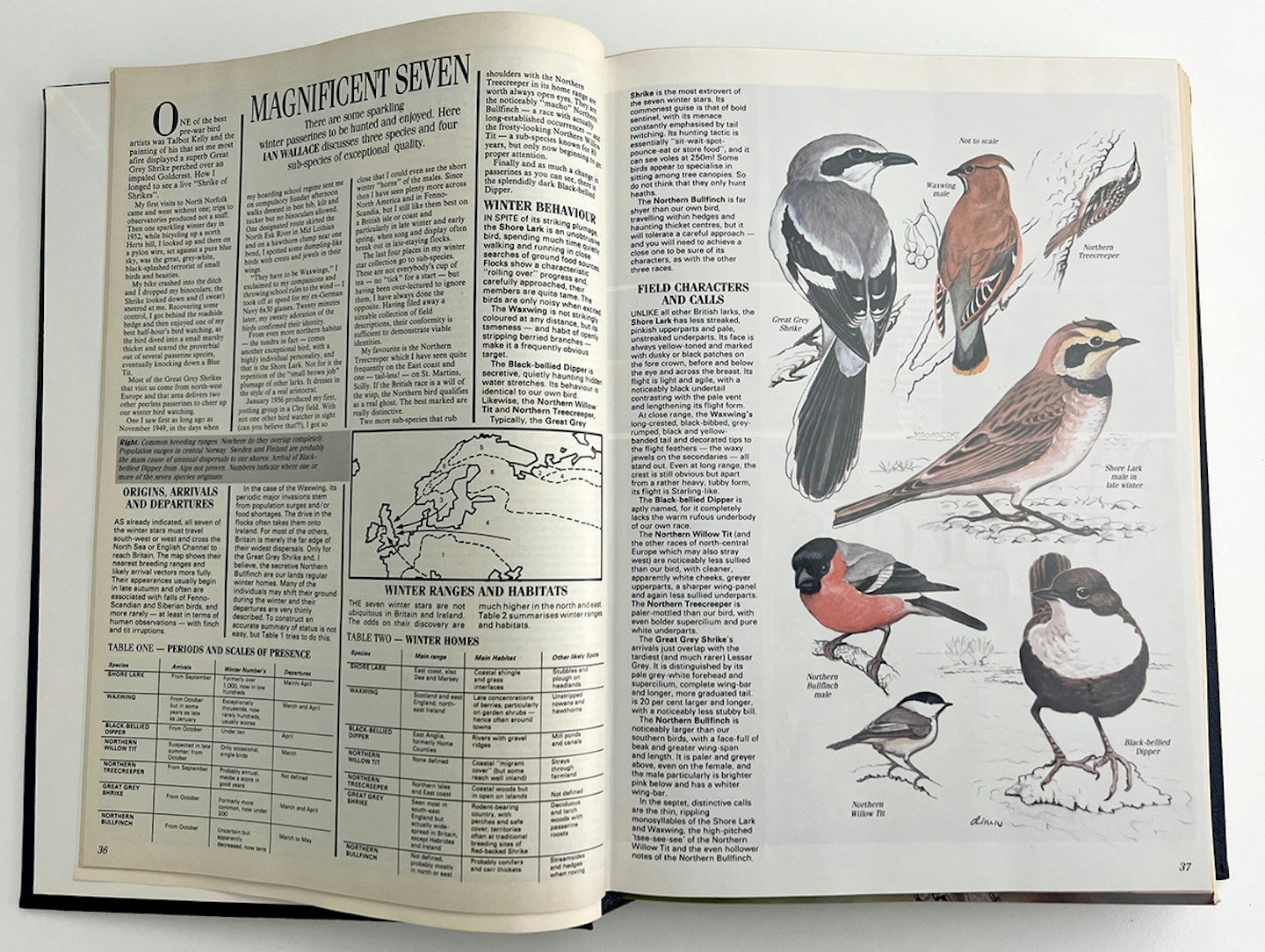

Unlike all other British larks, the Shore Lark has less streaked, pinkish upperparts and pale, unstreaked underparts. Its face is always yellow-toned and marked with dusky or black patches on the fore crown, before and below the eye and across the breast. Its flight is light and agile, with a noticeably black undertail contrasting with the pale vent and lengthening its flight form.

At close range, the Waxwing's long-crested, black-bibbed, grey-rumped, black and yellow- banded tail and decorated tips to the flight feathers – the waxy jewels on the secondaries – all stand out. Even at long range, the crest is still obvious but apart from a rather heavy, tubby form, its flight is Starling-like.

The Black-bellied Dipper is aptly named, for it completely lacks the warm rufous underbody of our own race.

The Northern Willow Tit (and the other races of north-central Europe which may also stray west) are noticeably less sullied than our bird, with cleaner, apparently white cheeks, greyer upperparts, a sharper wing-panel and again less sullied underparts.

The Northern Treecreeper is paler-mottled than our bird, with even bolder supercilium and pure white underparts.

The Great Grey Shrike's arrivals just overlap with the tardiest (and much rarer) Lesser Grey. It is distinguished by its pale grey-white forehead and supercilium, complete wing-bar and longer, more graduated tail. It is 20 per cent larger and longer, with a noticeably less stubby bill.

The Northern Bullfinch is noticeably larger than our southern birds, with a face-full of beak and greater wingspan and length. It is paler and greyer above, even on the female, and the male particularly is brighter pink below and has a whiter wing-bar.

In the septet, distinctive calls are the thin, rippling monosyllables of the Shore Lark and Waxwing, the high-pitched tsee-see-see of the Northern Willow Tit and the even hollower notes of the Northern Bullfinch.

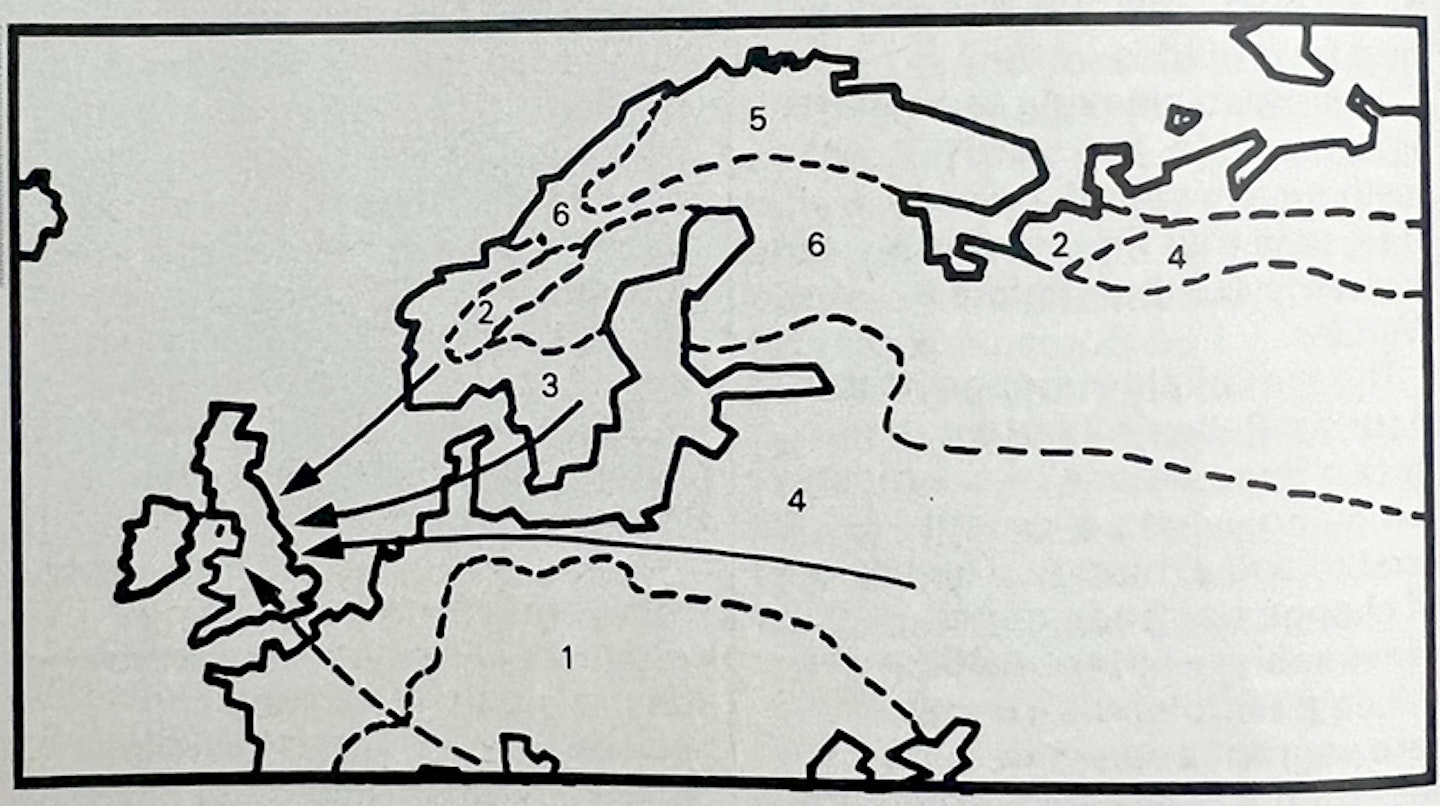

Common breeding ranges. Nowhere do they overlap completely

Population surges in central Norway

Sweden and Finland are probably, the main cause of unusual dispersals to our shores.

Arrival of Black-bellied Dipper from Alps not proven. Numbers indicate where one on more of the seven species originate

ORIGINS, ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES

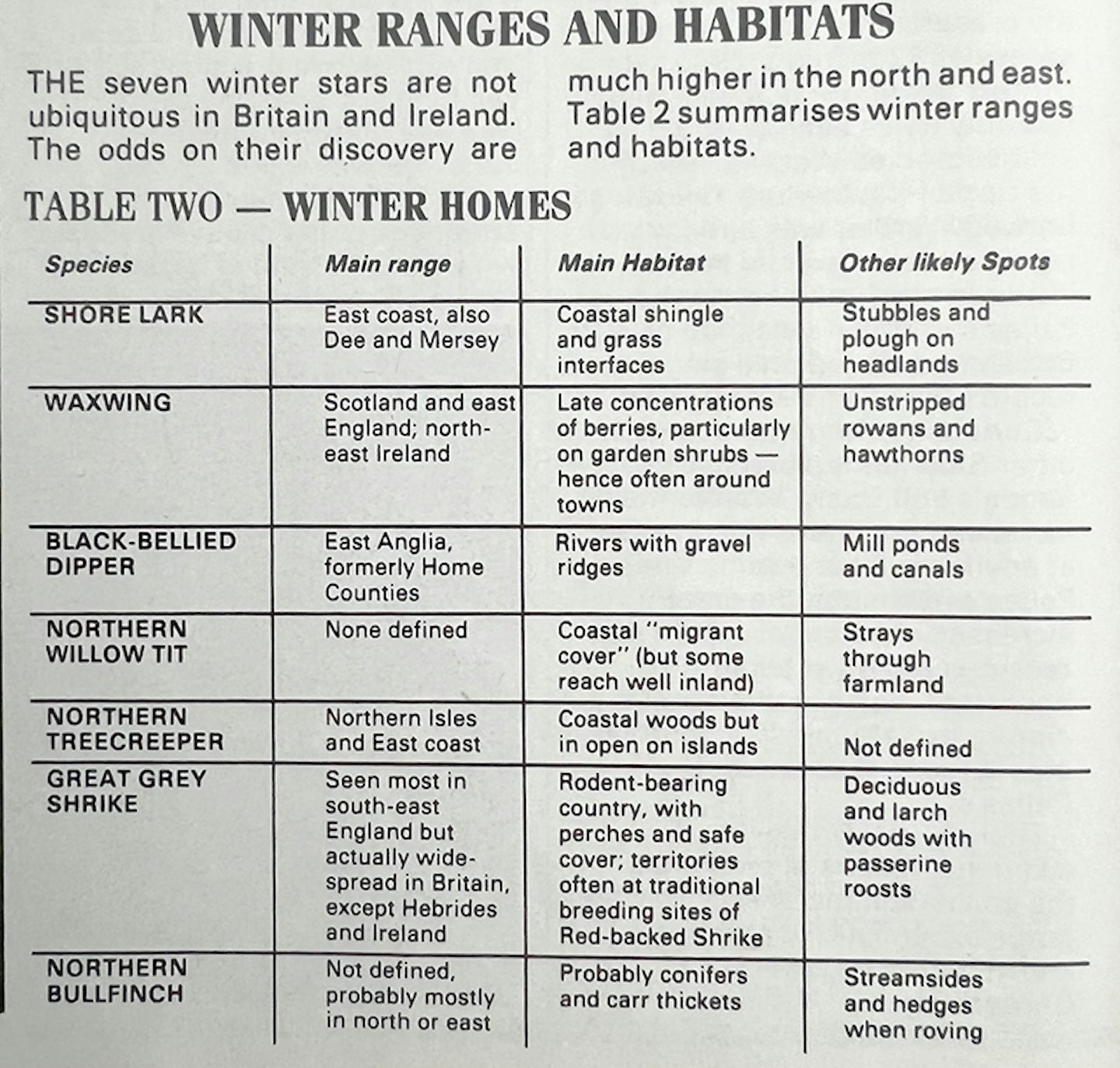

As already indicated, all seven of the winter stars must travel south-west or west and cross the North Sea or English Channel to reach Britain. The map shows their nearest breeding ranges and likely arrival vectors more fully.

Their appearances usually begin in late autumn and often are associated with falls of Fenno-Scandian and Siberian birds, and more rarely – at least in terms of human observations – with finchand tit irruptions.

In the case of the Waxwing, its periodic major invasions stem from population surges and/or food shortages. The drive in the flocks often takes them on to Ireland. For most of the others, Britain is merely the far edge of their widest dispersals.

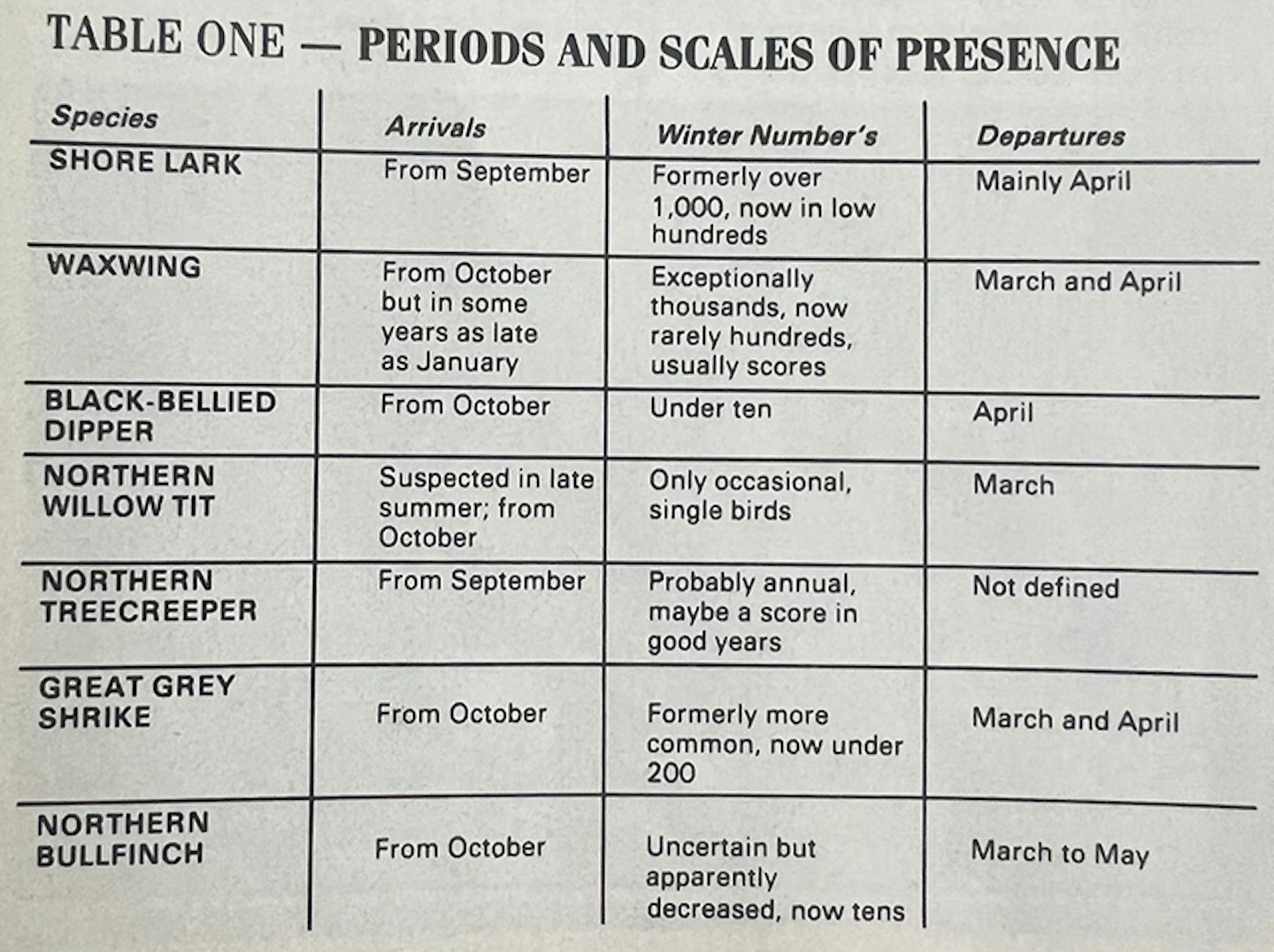

Only for the Great Grey Shrike and, I believe, the secretive Northern Bullfinch, are our lands regular winter homes. Many of the individuals may shift their ground during the winter and their departures are very thinly described. To construct an accurate summary of status is not easy, but Table 1 tries to do this.