Puzzling pipits

October 1986

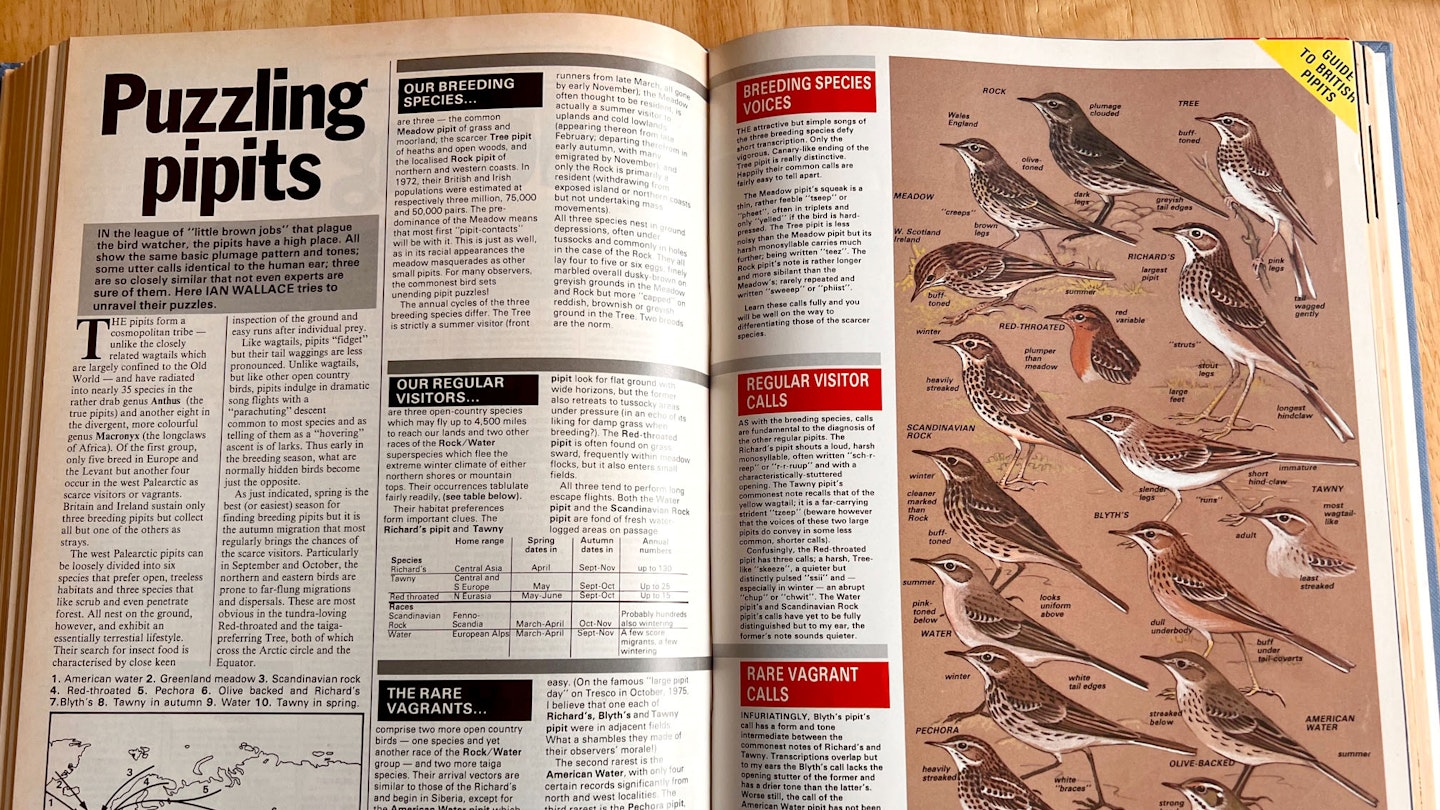

IN the league of "little brown jobs" that plague the birdwatcher, the pipits have a high place. All show the same basic plumage pattern and tones; some utter calls identical to the human ear: three are so closely similar that not even experts are sure of them. Here IAN WALLACE tries to unravel their puzzles

The pipits form a cosmopolitan tribe, unlike the closely related wagtails which are largely confined to the Old World,and have radiated into nearly 35 species in the rather drab genus Anthus (the true pipits); and another eight in the divergent, more colourful genus Macronyx (the longclaws of Africa). Of the first group, only five breed in Europe and the Levant, but another four occur in the west Palearctic, as scarce visitors or vagrants. Britain and Ireland sustain only three breeding pipits, but collect all but one of the others as strays.

The west Palearctic pipits can be loosely divided into six species that prefer open, treeless habitats and three species that like scrub and even penetrate forest. All nest on the ground, however, and exhibit an essentially terrestrial lifestyle. Their search for insect food is characterised by close keen inspection of the ground and easy runs after individual prey.

Like wagtails, pipits "fidget" but their tail waggings are less pronounced. Unlike wagtails, but like other open country birds, pipits indulge in dramatic song flights with a "parachuting" descent common to most species and as telling of them as a "hovering" ascent is of larks. Thus early in the breeding season, what are normally hidden birds become just the opposite.

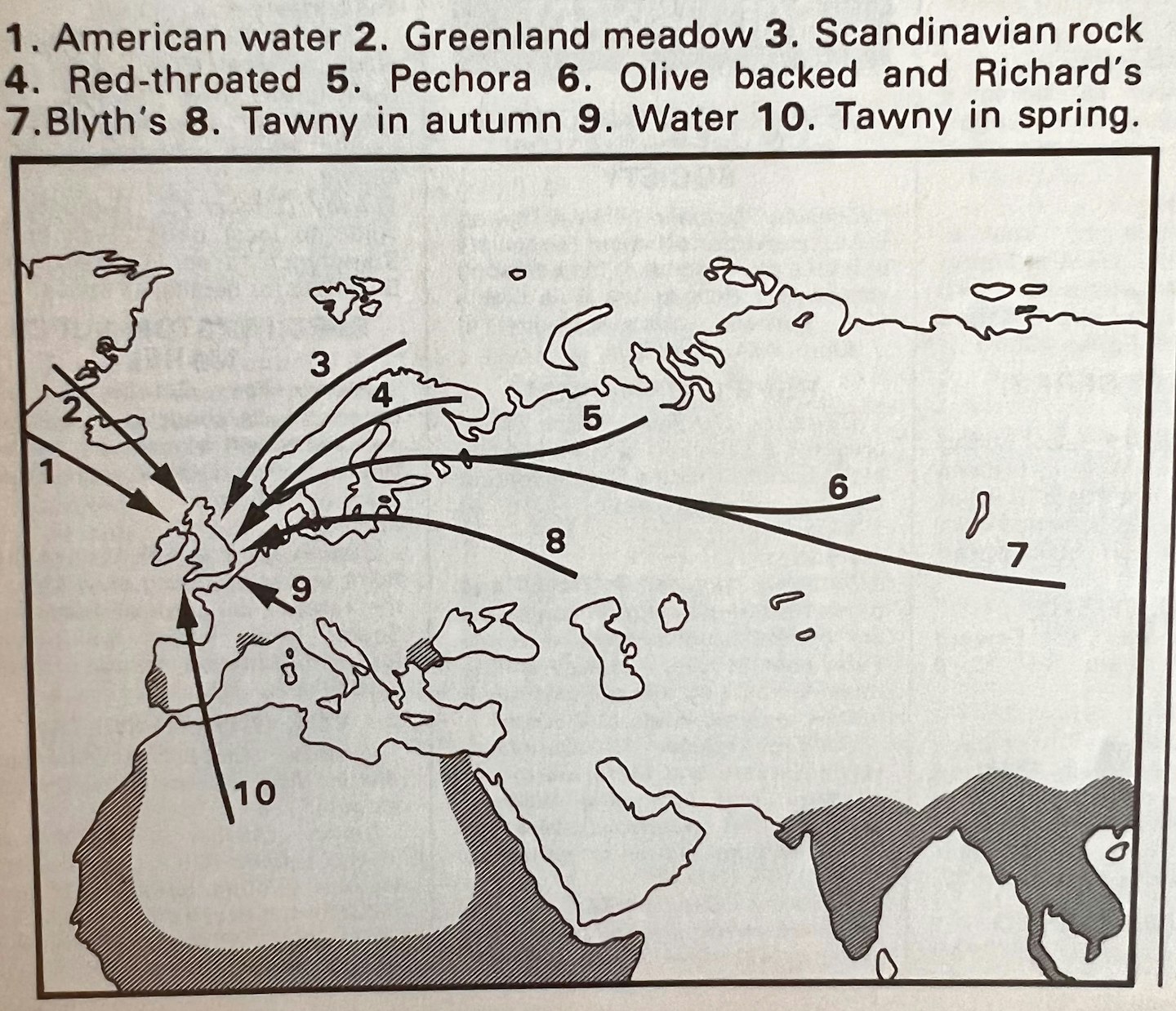

As just indicated, spring is the best (or easiest) season for finding breeding pipits, but it is the autumn migration that most regularly brings the chances of the scarce visitors. Particularly in September and October, the northern and eastern birds are prone to far-flung migrations and dispersals. These are most obvious in the tundra-loving Red-throated and the taiga- preferring Tree, both of which cross the Arctic circle and the Equator.

Our breeding species

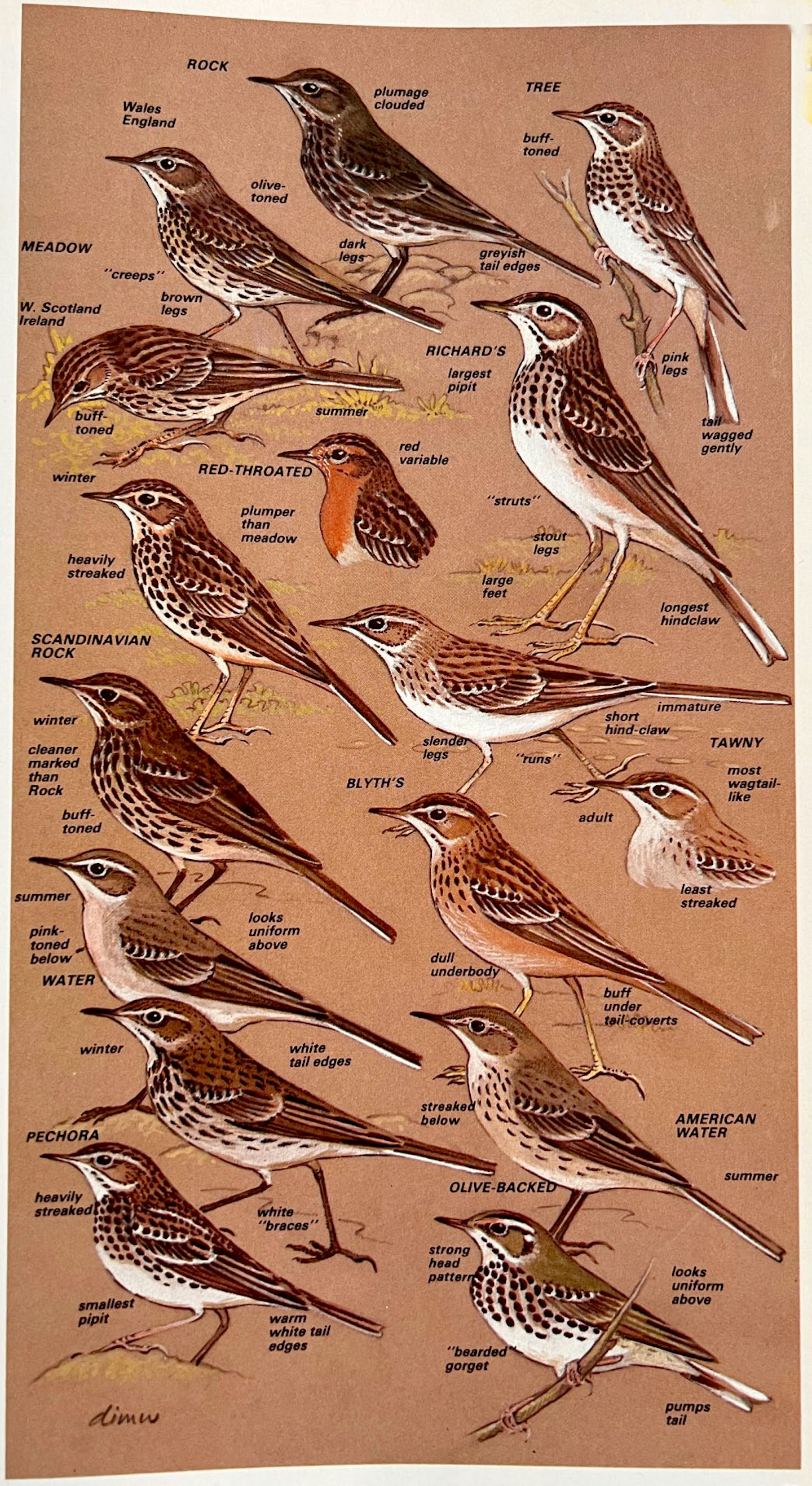

We have three breeding pipits – the common Meadow pipit of grass and moorland; the scarcer Tree pipit of heaths and open woods, and the localised Rock Pipit of northern and western coasts. In 1972, their British and Irish populations were estimated at respectively three million, 75,000 and 50,000 pairs. The pre-dominance of the Meadow means that most first "pipit-contacts" will be with it. This is just as well, as in its racial appearances the Meadow masquerades as other small pipits. For many observers, the commonest bird sets unending pipit puzzles!

The annual cycles of the three breeding species differ. The Tree is strictly a summer visitor (front runners from late March, all gone by early November); the Meadow often thought to be resident, is actually a summer visitor to uplands and cold lowlands (appearing thereon from late February; departing therefrom in early autumn, with many emigrated by November); and only the Rock is primarily a resident (withdrawing from exposed island or northern coasts but not undertaking mass movements).

All three species nest in ground depressions, often under tussocks and commonly in holes in the case of the Rock. They all lay four to five or six eggs, finely marbled overall dusky-brown on greyish grounds in the Meadow and Rock but more "capped" on reddish, brownish or greyish ground in the Tree. Two broods are the norm.

Breeding speices’ voices

the attractive but simple songs of the three breeding species defy short transcription. Only the vigorous, Canary-like ending of the Tree Pipit’s is really distinctive. Happily their common calls are fairly easy to tell apart. The Meadow pipit's squeak is a thin, rather feeble ‘tseep’ or ‘pheet’ often in triplets and only ‘yelled’ if the bird is hard-pressed. The Tree Pipit is less noisy than the Meadow Pipit but its harsh monosyllable carries much further; being written ‘teez’. The Rock Pipit's note is rather longer and more sibilant than the Meadow's; rarely repeated and written ‘sweeep’ or ‘phiist’ Learn these calls fully and you will be well on the way to differentiating those of the scarcer species.

Our regular visitors

Our regular visitors are three open country species which may fly up to 4,500 miles to reach our lands, and two other races of the Rock/Water superspecies which flee the extreme winter climate of either northern shires or mountain tips,. Their occurrences tabulate fairly readily.

Their habitat preferences form important clues. The Richar’d Pipit and Tawny Pipit look for flat ground with wide horizons, but the former also retreats to tussocky areas under pressure (in the echo it its liking for damp grass when breeding). The Red-throated Pipit is often forn on grass sward, frequently within Meadow Pipit flocks, but also enters small fields.

All three tend to perform long escape flights. Both the Water Pipit and Scandinavian Rock Pipit are fond of fresh water logged areas on passage.

Look for them at these times

Richard’s Pipit: April; September-November

Tawny Pipit: May; September-October

Red-throated Pipit: May-June; September-October

Scandinavian Rock Pipit: March-April; October-November

Water Pipit: March-April; September-November

Regular visitor calls

As with the breeding species, calls are fundamental to the diagnosis of the other regular pipits. The Richard's pipit shouts a loud, harsh monosyllable, often written ‘sch-r-reep’ or ‘r-r-ruup’ and with a characteristically-stuttered opening. The Tawny pipit's commonest note recalls that of the yellow wagtail; it is a far-carrying strident ‘teep’ (beware however that the voices of these two large pipits do convey in some less common, shorter calls).

Confusingly, the Red-throated pipit has three calls: a harsh, Tree-like ‘skeeze’ a quieter but distinctly pulsed ‘ssil’ and especially in winter ‘chup’ an abrupt or ‘chwit’ The Water Pipit's and Scandinavian Rock Pipit's calls have yet to be fully distinguished but to my ear, the former's note sounds quieter.

The rare vagrants

These comprise two more open country birds, one species and yet another race of the Rock/Water group – and two more taiga species. Their arrival vectors are similar to those of the Richard's and begin in Siberia, except for the American Water Pipit [=American Buff-bellied Pipit] which strays east across the Atlantic.

The rarest is the so far once- only Blyth's Pipit from east- central Asia, of which a shrunk skin spent 75 years in a British Museum drawer before the late Kenneth Williamson finally solved its puzzle and won its acceptance as a Sussex vagrant of October 1882. It may occur more often but getting a proper debate on its true status is not easy. (On the famous "large pipit day" on Tresco in October, 1975, I believe that one each of Richard's, Blyth's and Tawny Pipits were in adjacent fields. What a shambles they made of their observers' morale!).

The second rarest is the American Water, with only four certain records significantly from north and west localities. The third rarest is the Pechora pipit, its 20 odd appearances still virtually confined to Fair Isle in autumn but in my view simply overlooked or unheard. The last, now annual, vagrant is the beautifully decorated Olive-backed pipit, whose mounting occurrences now match those of the Siberian warblers and exceed 25. It, like the Pechora, travels with Tree pipits and freely enters woods en passage.

Rare vagrant calls

Infuriatingly, Blyth's Pipit's call has a form and tone intermediate between the commonest notes of Richard's and Tawny. Transcriptions overlap, but to my ears the Blyth's call lacks the opening stutter of the former and has a drier tone than the latter's. Worse still, the call of the American Water Pipit has not been separated at all. Conversely, the note of the Pechora Pipit is distinctive an abrupt, stony ‘pit’, without the squeakiness of Meadow, but also repeated in two and three note phrases. Unhappily pipit puzzles return again with the Olive-backed Pipit's voice, for its commonest call written ‘skeaze’ echoes those of both Tree and Red-throated.

2020s update

These days, Water Pipit and Rock Pipit are considered separate species. Water Pipits, though still seen on passage, of course, also overwinter in smallish numbers at selected sites.

What DIMW calls the American Water Pipit, is now called the American Buff-bellied Pipit or just the Buff-bellied Pipit (or even just the American Pipit). This is a rare but regular visitor each autumn, mainly to Scilly and Shetland.

The most recent estimates of our breeding pipit populations are:

Meadow Pipit: 2,000,000 pairs

Tree Pipit: 88,000 pairs

Rock Pipit: 34,000 pairs