Exiles from the East

April 1986

TEN years ago, few ornithologists would have forecast that two new buntings would have joined the British List. Both came from Siberia and so the prizes for the bunting hunter can be rich. In this article IAN WALLACE describes both regular and irregular species, with special emphasis on their calls. In his travels from Iceland to Mongolia he has seen them all but still enjoys even the commonest in his new study area of Staffordshire.

BUNTING-LIKE passerines occur right round the Northern Hemisphere and in the Tropics, but Europe's tree, bush, or ground-haunting buntings come from only four genera: Milaria, solely occupied by the puzzling Corn Bunting; Emberiza, most typified by the dazzling Yellowhammer; Plectrophenax containing the lovely Snow Bunting; and Calcarias, the Lapland Bunting, whose Latin name means "spurred' and describes its long hind toe claw.

Of 32 Palearctic species, at least 16 visit Britain and Ireland. Six breed or winter regularly and ten or more come on passage as far as eastern Siberia (see The Furthest Wanderer).

Excepting the Corn, all the British buntings exhibit marked sexual dimorphism; some of the cocks rank among the world's most beautiful-looking songbirds. Their essentially finch-like forms end invariably in long tails, characteristic of their tribe. Much of their behaviour, for example post-breeding flocking and ground feeding, also echoes that of the finches, but in the main they are rather poor songsters, content with tuneless repetitive phrases.

Unlike finches, buntings have adapted little to the presence of man, shunning town parks and all but the longest gardens. Thus it is the least-disturbed countryside and marshes that hold most of them. Even so, their distribution is uneven. Only the Yellowhammer and the Reed Bunting are widespread, the latter having entered the much-enlarged acreage of cereals in the last 30 years. Curiously, local or peripheral north of central England, the Corn Bunting is absent from Wales and central Ireland. The relatively tiny breeding ranges of the Cirl, Snow and Lapland are noted below.

In winter, the occurrences of buntings often widens. One annual phenomenon is the large arrival of the Snow Bunting, whose flocks rove the Northern Isles and east coast of Britain, forming living snow storms. The smaller parties of immigrant Lapland Buntings are often joined by Shore Larks, also from Fenno-Scandia. Their survival task is to glean every last seed from the ground.

Buntings are never easy game but they are well worth the foot slog and keen-eyed concentration needed to find them. Sadly no modern book deals fully with them: the Handbook remains the fullest reference to them

• Palearctic: Zoogeographical region comprising Europe, Africa north of Sahara and Asia north of Himalayas.

• Sexual dimorphism: Difference in appearance between male and female.

THE BREEDING SPECIES

Six buntings breed or have bred in Britain, but only three are common – the Yellowhammer (one million pairs), the reed bunting (500,000 pairs) and the Corn Bunting (up to 30,000). Next comes the retreating Cirl Bunting (see below) and last on a few Scottish mountains after long winters, the rare snow bunting (up to ten pairs) and the Lapland bunting (one pair once). The farmland birds nest low in bushes or weeds, lay three to five eggs. These are pale grey to brown, and boldly marked in the Corn Bunting; white to pale green, finely striated in the Yellowhammer. Both have flying young within 3½ weeks.

The tussock-nesting Reed Bunting lays four or five eggs (pale brown to olive, little marked) and takes four weeks for fledging. All three raise two, even three, broods. In their much shorter, Alpine summer, the rock-nesting snow and the ground-nesting Lapland raise usually one brood in three weeks. Their four-six (in good years seven) eggs are red blotched.

The most distinctive sounds of these buntings are the jangling keys songs of the corn, and the little bit of bread and no cheese ditty of the Yellowhammer, the thin tseep call of the reed, the lilting ripple of the snow and the flat, ticked rattle of the Lapland.

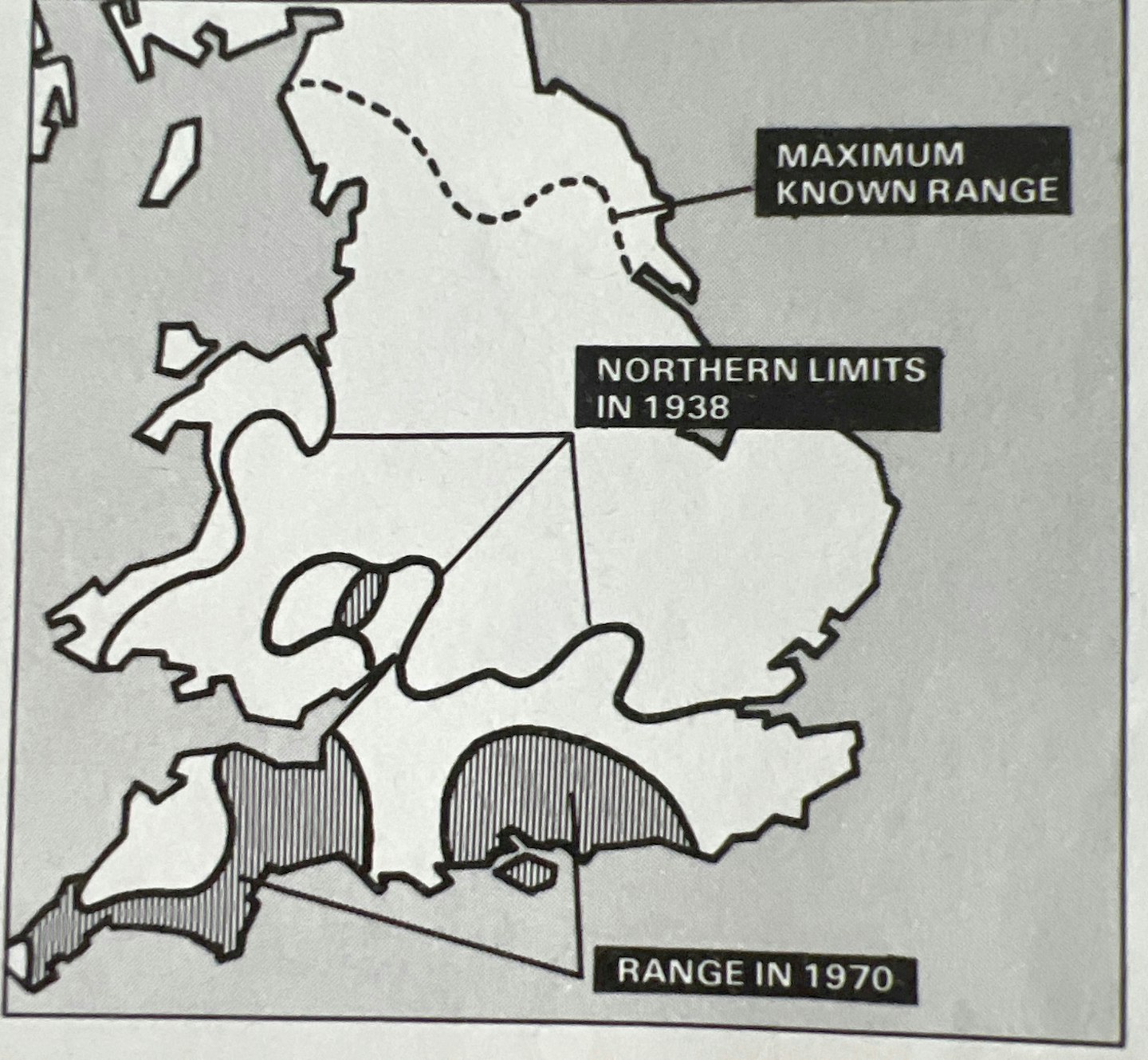

CLOSE TO EXTINCTION

....that's the fate of the Cirl Bunting. Once touching Cumbria, its range has collapsed south and west in the last 50 years. Only Devon with at least 130 pairs, can now claim more than a relict scatter of birds. Little prone to wander, the Cirl recruits no fresh blood from Europe and may lose its British place. The Cirl's breeding biology is like the Yellowhammer's, but cocks are prone to sit on tall hedgerow Elms, rattling out their tinny song. Beware mistaking them for Lesser Whitethroats and vice versa. The eggs are pale blue or green, boldly marked. Two broods are the rule for this unobtrusive but, in the male, striking bird.

THE REGULAR MIGRANTS

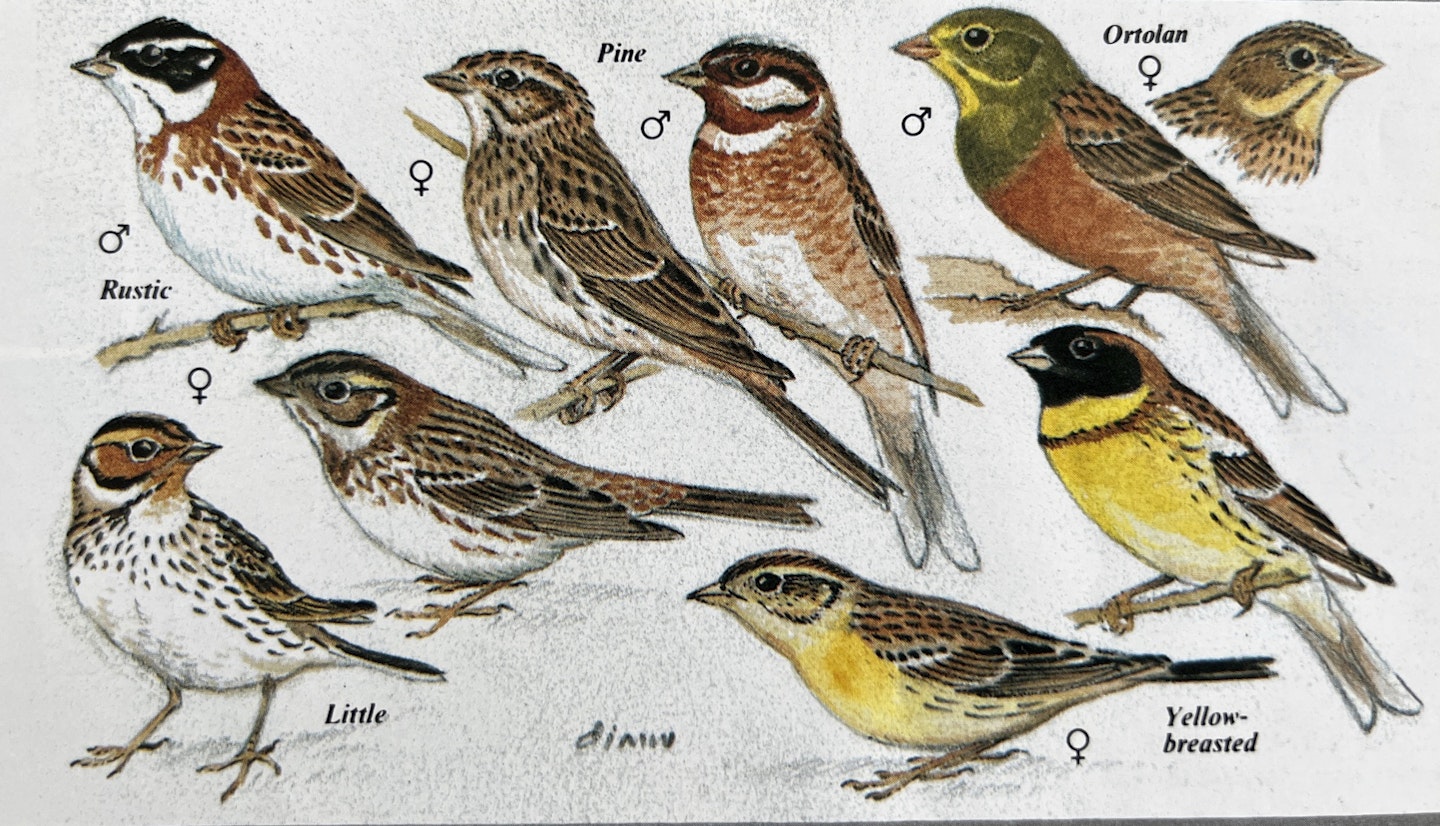

Once apparently confined to Fair Isle, several uncommon buntings now occur annually on the east coast and isles of Britain. Their regularity smacks of displaced migration, not mere vagrancy. The longest known is the ortolan bunting whose Finno-Scandian population 'overshoot' in the spring and autumn.

It is increasingly tailed by the Little Bunting (see right), the rustic and the Yellow-breasted Buntings, which cross the North Sea in May/June and September /November, and the Pine Bunting which is now following them in autumn and even winter, all the way from Siberia. No single cause for these increases exists increased observation, range expansion, exceptional breeding success, reversed migration, and 'drift' on the persistent easterlies of recent autumns are all part of the equation.

Calls are crucial in bunting identification. The Ortolan gives a quiet, liquid 'plip' on take-off; the rustic a quite loud 'tick' or 'tip : the yellow-breasted a short 'zipp'. The pine is less heloful. Closely related to the Yellowhammer, it sounds just like it. Even so an odd call from a bunting always causes a missed heartbeat in an expert bird watcher. If the bird is smaller and less long-tailed than the Yellowhammer or the reed, it is worth a second and a third look.

THE SECRET WINTERER

...is the Little Bunting. Up to the 1970s, most birdwatchers looked for it only in autumn. Yet two old winter records from Ireland and some March and April occurrences – hinted at another status. Now it is certain that a few westward-straying birds settle for a rainy British winter rather than struggle back to a steamy Asian one. Identifying the Little Bunting is tricky, but its ticking call, flicked (not fanned) and straight-edged tail and bright, intense head pattern show well at close range. The song is Robin-like. Will it eventually be heard from a Scottish willow bog in summer? A few breed as close as Lapland.

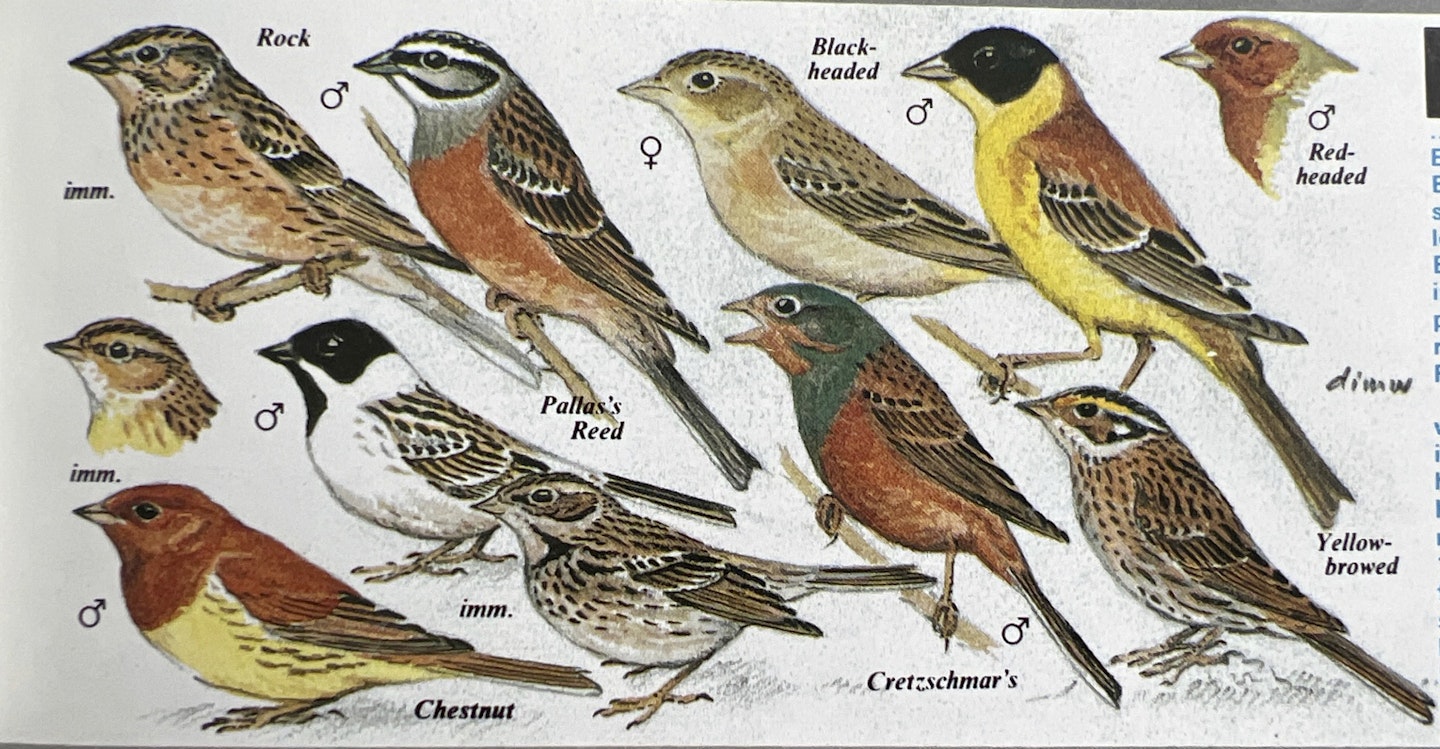

THE RARE VAGRANTS

Most buntings are long-distance migrants; those that should withdraw south or south-east from northern Asia are prone to 'overshooting' and reversed migration' Two groups occasionally reach Britain. In the first are the Rock Bunting (of which some live as close as Iberia), the Cretzschmar’s, the Black-headed, and perhaps the Red-headed. All these may move N, NW or W from the Mediterranean and south-west Asia, appearing as adults in spring and summer or more rarely as lost immatures in autumn. In the second group are the Pallas's reed, the yellow browed (see right) and perhaps the chestnut. These usually arrive from Siberia in the vast fan of juvenile autumn dispersal. The 'perhaps' in front of the Red-headed and the chestnut are necessary because they are common captives of the cage bird trade. This ugly business clouds the judgement of true vagrancy, so neither species is officially a British bird yet.

Again, form and call are important to identification. The slim Rock Bunting gives a sharp 'tit' (like the Cirl); the rather small compact Cretzschmar's a loud "'styip' (more insistent than the ortolan); the Black-headed a full 'chup'; the rather large red- headed a musical 'tweet; the small Pallas's reed a sparrow-like "chee-ulp'; and the small, dumpy chestnut a thin 'tseep'

THE FURTHEST WANDERER

...is the Yellow-browed Bunting. Breeding no nearer than Lake Baikal in central Asia, no other small passerine has survived a longer journey to reach western Europe. First recorded in France in 1930, increased rarity hunting produced two modern British records Norfolk in 1975 and Fair Isle in 1980. The Yellow-browed's Chinese winter quarters lie due south of its summer range; the usual hypothesis of reversed migration hardly explains the astonishing migration due west. Yet both the 1975 and 1980 birds appeared in floods of other west Siberian species. The yellow-browed calls like the Little Bunting, but its bigger bill, white crown stripe and yellow supercilium catch the eve.

DIM Wallace wrote this article in the mid-1980s, and although his advice remains excellent, much has changed in UK bird populations in recent decades. Here are some of the more significant changes since this feature was originally published in BW

2020s update:

There are now 19 bunting species on the British List, with the more recent additions of Chestnut-eared Bunting, Black-faced Bunting and Chestnut Bunting.

Yellow-breasted Buntings have declined in their Asian breeding range almost to extinction, so are now extremely rare visitors to the UK.

The Yellowhammer’s UK breeding population is now estimated at 700,000 pairs; the Reed Bunting’s 250,000 pairs; Corn Bunting 11,000 pairs.

Countering these declines, the Cirl Bunting’s breeding population has risen to more than 1,000 pairs (partly owing to reintroduction in Cornwall); and Snow Bunting more than 60 pairs

There were three further accepted UK records of Yellow-browed Bunting in the 1990s but none since the turn of the Millennium