Calls from the past - part 2

February 1987

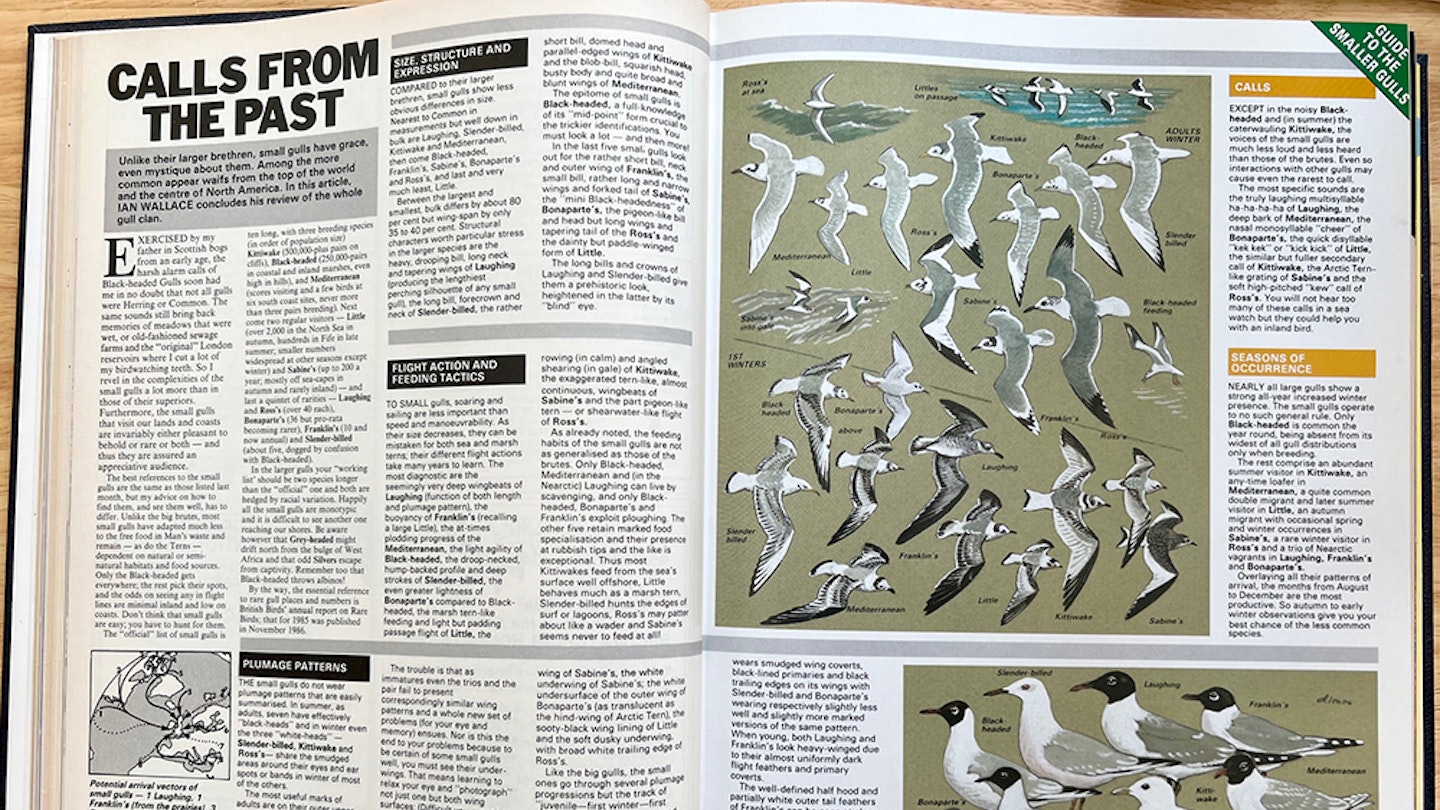

Unlike their larger brethren, small gulls have grace, even mystique about them. Among the more common appear waits from the top of the world and the centre of North America. In this article, Ian Wallace concludes his review of the whole gull clan.

Exercised by my father in Scottish bogs from an early age, the harsh alarm calls of Black-headed Gulls soon had me in no doubt that not all gulls were Herring or Common. The same sounds still bring back memories of meadows that were wet, or old-fashioned sewage farms and the ‘original’ London reservoirs where I cut a lot of my birdwatching teeth.

So I revel in the complexities of the small gulls a lot more than in those of their superiors. Furthermore, the small gulls that visit our lands and coasts are invariably either pleasant to behold or rare or both – and thus they are assured an appreciative audience.

The best references to the small gulls are the same as those listed last month, but my advice on how to find them, and see them well, has to differ. Unlike the big brutes, most small gulls have adapted much less to the free food in Man's waste and remain – as do the terns, dependent on natural or semi-natural habitats and food sources.

Only the Black-headed gets everywhere; the rest pick their spots, and the odds on seeing any in flight lines are minimal inland and low on coasts. Don't think that small gulls are easy; you have to hunt for them. The ‘official’ list of small gulls is 10 long, with three breeding species (in order of population size) Kittiwake (500,000-plus pairs on cliffs), Black-headed (250,000-pairs in coastal and inland marshes, even high in hills), and Mediterranean (scores visiting and a few birds at six south coast sites, never more than three pairs breeding).

Next come two regular visitors – Little (over 2,000 in the North Sea in autumn, hundreds in Fife in late summer; smaller numbers widespread at other seasons except winter) and Sabine's (up to 200 year; mostly off sea-capes in autumn and rarely inland) and last a quintet of rarities – Laughing and Ross's (over 40 each), Bonaparte's (36 but pro-rata becoming rarer), Franklin's (10 and now annual) and Slender-billed (about five, dogged by confusion with Black-headed). In the larger gulls your ‘working list' should be two species longer than the ‘'official’ one and both are hedged by racial variation.

Happily, all the small gulls are monotypic and it is difficult to see another one reaching our shores. Be aware, however, that Grey-headed might drift north from the bulge of West Africa and that odd Silvers escape from captivity. Remember, too, that Black-headed throws up albinos! By the way, the essential reference to rare gull places and numbers is British Birds' annual report on Rare Birds; that for 1985 was published in November 1986.

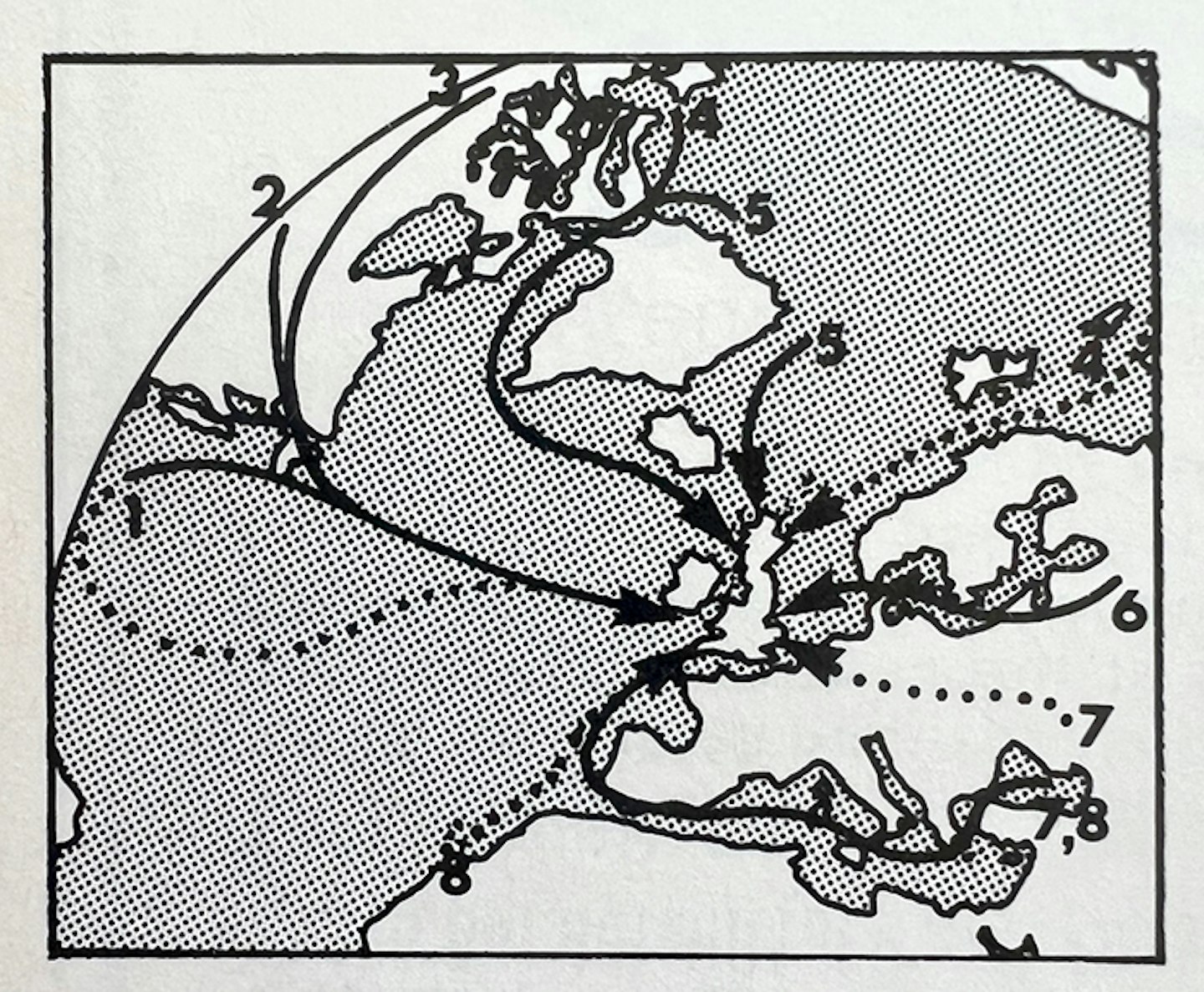

Potential arrival vectors of small gulls

1 Laughing, Franklin’s (from the prairies), 3 Bonaparte's, 4 Ross’s (certainly • from North Neararctic, perhaps from East Palearctic), 5 Sabine 's, 6 Little, 7 Mediterranean (some across Europe, most via its own sea) and 8 Slender-billed (origin unknown, perhaps fellow travelling with Mediterranean, or through not turning right at the Strait's of Gibraltar).

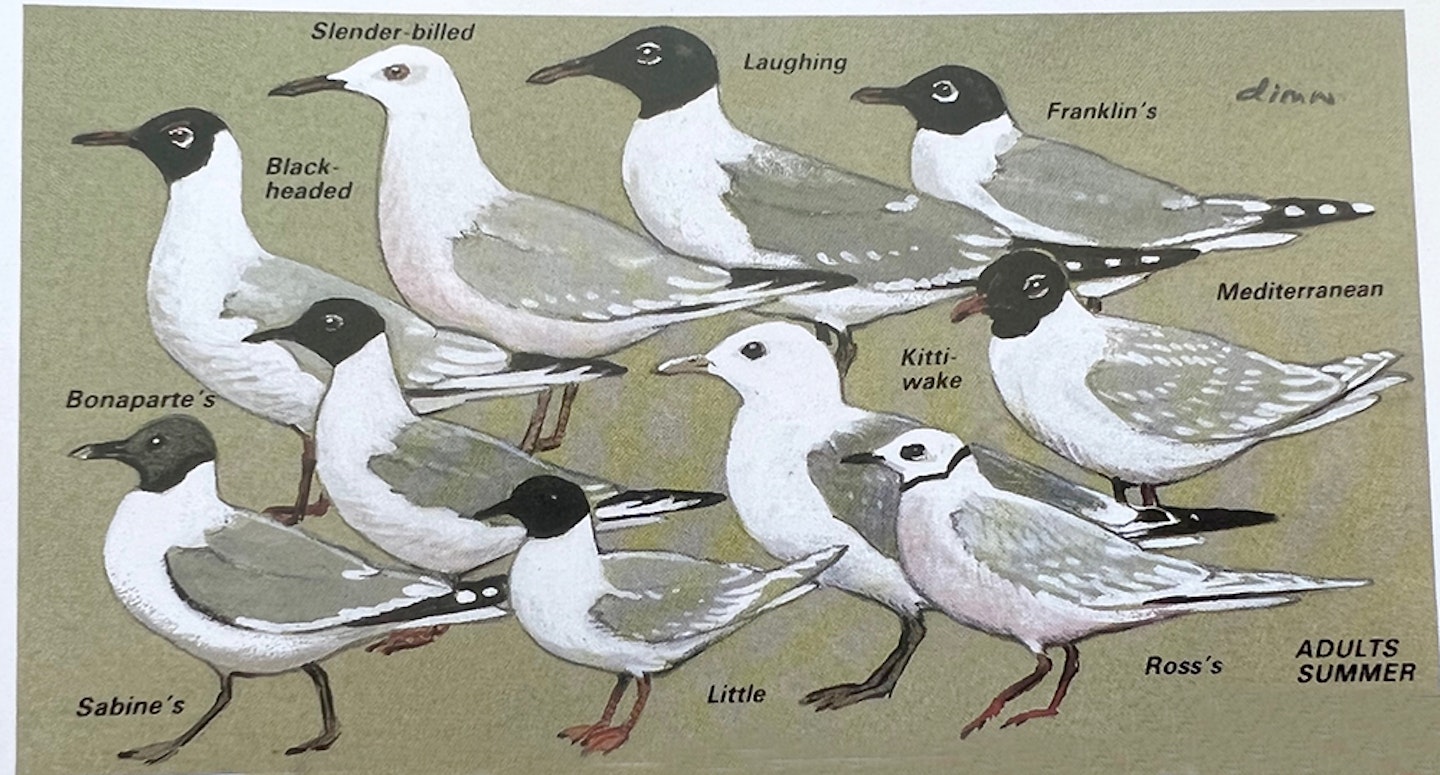

Size, structure and expression

Compared with their larger brethren, small gulls show less obvious differences in size. Nearest to Common in measurements, but well down in bulk are Laughing, Slender-billed, Kittiwake and Mediterranean. Then come Black-headed, Franklin's, Sabine's, Bonaparte's and Ross's. Last and very much least, Little.

Between the largest and smallest, bulk differs by about 80% but wing-span by only 35 to 40%.

Structural characters worth particular stress in the larger species are the heavy, drooping bill, long neck and tapering wings of Laughing (producing the lengthiest perching silhouette of any small gull); the long bill, forecrown and neck of Slender-billed; the rather short bill, domed head and parallel-edged wings of Kittiwake; and the blob-bill, squarish head, busty body; and quite broad and blunt wings of Mediterranean.

The epitome of small gulls is Black-headed, a full-knowledge of its mid-point form is crucial to the trickier identifications. You must look a lot and then more!

In the last five small gulls, look out for the rather short bill, neck and outer wing of Franklin's; the small bill, rather long and narrow wings and forked tail of Sabine’s; the mini Black-headedness’ of Bonaparte's; the pigeon-like bill and head but long wings and tapering tail of the Ross’s; and the dainty but paddle-winged form of Little.

The long bills and crowns of Laughing and Slender-billed give them a prehistoric look, heightened in the latter by its ‘blind’ eye.

Flight action and feeding tactics

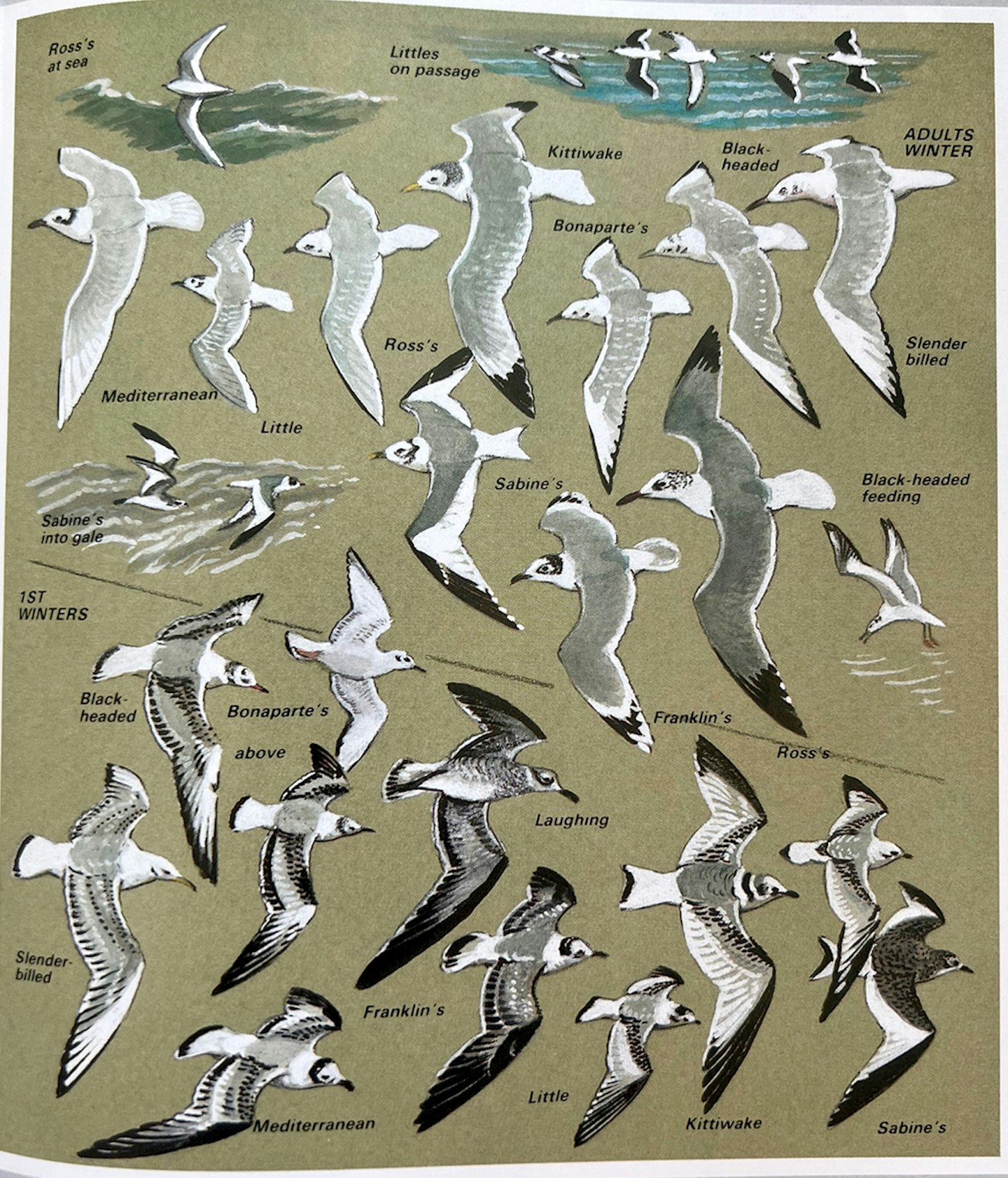

To small gulls, soaring and sailing are less important than speed and manoeuvrability. As their size decreases, they can be mistaken for both sea and marsh terns; their different flight actions take many years to learn.

The most diagnostic are the seemingly very deep wingbeats of Laughing (function of both length and plumage pattern); the buoyancy of Franklin’s (recalling a large Little); the at-times plodding progress of the Mediterranean; the light agility of Black-headed; the droop-necked, hump-backed profile and deep strokes of Slender-billed; the even greater lightness of Bonaparte's compared to Black headed; the marsh tern-like feeding and light but padding passage flight of Little; the rowing (in calm) and angled shearing (in gale) of Kittiwake; the exaggerated tern-like, almost continuous, wingbeats of Sabine's; and the part pigeon-like tern or shearwater-like flight of Ross's.

As already noted, the feeding habits of the small gulls are not as generalised as those of the brutes. Only Black-headed, Mediterranean and (in the Nearctic) Laughing can live by scavenging, and only Black-headed, Bonaparte's and Franklin's exploit ploughing.

The other five retain marked food specialisation and their presence at rubbish tips and the like is exceptional. Thus, most Kittiwakes feed from the sea's surface well offshore, Little behaves much as a marsh tern, Slender-billed hunts the edges of surf or lagoons, Ross's may patter about like a wader and Sabine’s seems never to feed at all!

Calls

Except in the noisy Black-headed and (in summer) the caterwauling Kittiwake, the voices of the small gulls are much less loud and less heard than those of the brutes. Even so interactions with other gulls may cause even the rarest to call. The most specific sounds are the truly laughing multisyllable ‘ha-ha-ha-ha’ of Laughing, the deep bark of Mediterranean, the nasal monosyllable ‘cheer’ of Bonaparte's, the quick disyllable ‘kek kek’ or ‘kick kick’ of Little, the similar but fuller secondary call of Kittiwake, the Arctic Tern-like grating of Sabine's and the soft high-pitched ‘kew’ call of Ross's. You will not hear too many of these calls in a sea watch, but they could help you with an inland bird.

Seasons of occurrence

Nearly all large gulls show a strong all-year increased winter presence. The small gulls operate to no such general rule. Only Black-headed is common the year round, being absent from its widest of all gull distributions only when breeding. The rest comprise an abundant summer visitor in Kittiwake, an any-time loafer in Mediterranean, a quite common double migrant and later summer visitor in Little, an autumn migrant with occasional spring and winter occurrences in Sabine's, a rare winter visitor in Ross ‘s and a trio of Nearctic vagrants in Laughing, Franklin's and Bonaparte’s. Overlaying all their patterns of arrival, the months from August to December are the most productive. So, autumn to early winter observations give you your best chance of the less common species.

Plumage patterns

The small gulls do not wear plumage patterns that are easily summarised. In summer, as adults, seven have effectively ‘black heads’, and in winter even the three ‘white heads’. Slender-billed, Kittiwake and Ross's-share the smudged areas around their eyes and ear spots or bands in winter of most of the others.

The most useful marks of adults are on their outer upper wings, with a trio of ‘white leading edges’ Slender-billed, Black-headed and Bonaparte's – another trio of ‘white ends or rims’ Mediterranean, Ross's and Little a pair of ‘black ends’ – Laughing and especially Kittiwake one ‘black leading triangle’ Sabine's and finally one ‘white black white patchwork’ Franklin' s.

The trouble is that as immatures, even the trios and the pair fail to present correspondingly similar wing patterns and a whole new set of problems (for your eye and memory) ensues.

Nor is this the end to your problems because to be certain of some small gulls well, you must see their under-wings. That means learning to relax your eye and ‘photograph’ not just one but both wing surfaces: (Difficult you may think, but with practice you will be able to spot nuances like the illusion caused by almost black underwing of an adult Little which makes the wing disappear against a dark sea.

It is this sort of clue that only really skilled eyes can read.

In the morass of small gull characters, some adult marks are instantly diagnostic. These are the ‘three triangles ' of the upper wing of Sabine's, the white underwing of Sabine's; the white under-surface of the outer wing of Bonaparte's (as translucent as the hind-wing of Arctic Tern); the sooty-black wing lining of Little; and the soft dusky underwing, with broad white trailing edge of Ross's.

Like the big gulls, the small ones go through several plumage progression: but the track of ‘juvenile, first-winter, first- summer, second-winter, second-summer, third-winter, adult’ covers most of them. So, there is somewhat less to learn than with the brutes.

As already noted, groups of adult plumage pattern are not preceded by correspondingly common, immature, dress. Young Kittiwake, Sabine's, Ross's and Little exhibit more or less striking zig-zag patterns across wings and saddle. Immature Black-headed wears smudged wing coverts, black-lined primaries and black trailing edges on its wings; with Slender-billed and Bonaparte's wearing respectively slightly less well and slightly more marked versions of the same pattern.

When young, both Laughing and Franklin's look heavy-winged due to their almost uniformly dark flight feathers and primary coverts. The well-defined half hood and partially white outer tail feathers of Franklin's can be seen at close range and the dusky breast, flanks and underwing of Laughing look ‘dirty at all races.

Last comes the immature Mediterranean which looks far more like a young Common than Black-headed. One last thought, learn the common gulls well and then you will spot the rare ones more quickly and surely.

2020s update

There are now probably more than 1,000 pairs of Mediterranean Gull nesting in the UK (it is a much more numerous bird than it was in the 1980s). Little Gull has bred just once in the UK.

Bonaparte’s Gull is now a much more common rare gull in the UK; although this perception is partly because several birds have become effectively resident, being seen at the same site for many years (it is, after all a better option than dying or trying to get back over the Atlantic to North America).