When you pick up your field guide to try to identify different species, have you ever wondered how the first field guides came about?

Words by John Miles

Several bird books did appear in historic times, but two stand out which set the scene for all field guides to follow – A History of British Birds – Land Birds, in 1797, followed by Water Birds in 1804.

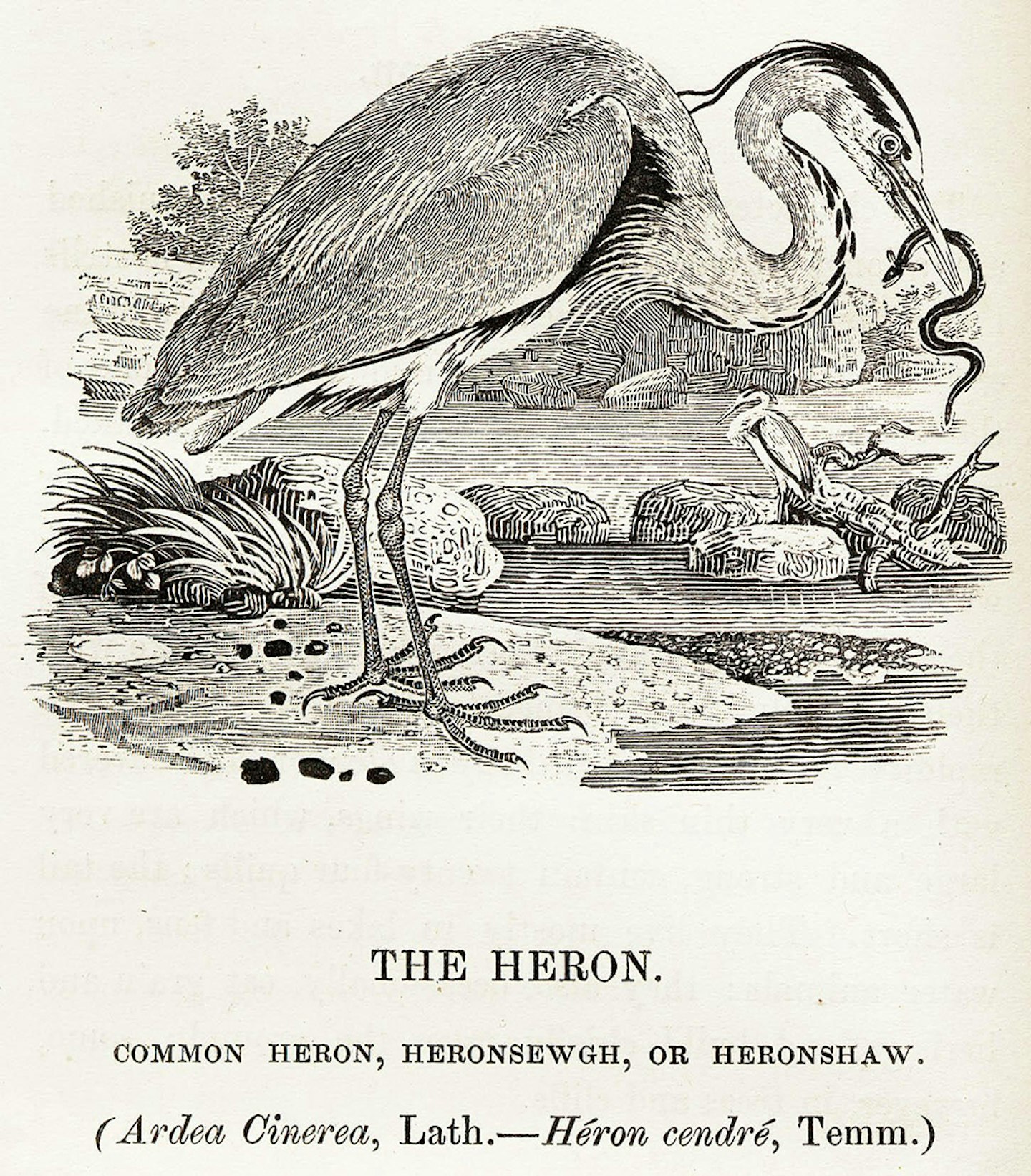

Thomas Bewick was the man who brought these books to the British people. Every image in them was done as a ‘wood cut’, with the main part of the picture being the bird, with a small scene (usually its typical habitat) in the background. Printing was a different job in those days, and each bird was carved out on wood from the Box tree. Most of Bewick’s work was so small – 8cm wide to 3.8cm high – that the quality is astonishing. Imagine trying to carve out a bird at that size, and add a landscape behind!

The reaction to the books was astonishing, too. “I have never before seen the character and attitude of the birds so admirably drawn”, wrote one critic. A mother claimed about her child: “From four to five hours a day, the little fellow looks through the book and now can tell the name of almost every bird”. The Brontë sisters had copies, and in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, the title character takes refuge in her copies of Bewick’s work.

Early days

Thomas Bewick was brought up on a farm on the Tyne near Newcastle, called ‘Cherryburn’. This is now a National Trust property, showing off a lot of Thomas’s wood-cuts, and the machines that made the wood-cuts into images in books and magazines. He was born there in 1753, and by the age of 14, was working in Newcastle, where he had lodgings from which he walked home the 12 miles every weekend.

His dad ran a coal mine, and it was there where Thomas learned about fossils 200 feet below the surface. This knowledge of natural science meant that he was not a religious man. Around the farm, the River Tyne and surrounding countryside, Thomas learned about wildlife. He loved to wander on his own and find bird’s nests and look atflowers and trees, but with a river on his doorstep, fishing was also a great pastime.

Thomas started work as an apprentice with the Beilby family in a print works, where he was signed on for seven years, so as not to give away trade secrets! There, his artwork flourished and the wood-cuts were often seen as superior to copper engravings. His early work was used by businesses for their advertising and where he could, Thomas would add his birds and mammals with a background. His work was so admired that they were described as “songs on wood”!

Even in those days, the draw to work in London was what the best workers often did, but after his apprenticeship, Thomas only stayed there for a short time, describing it as “the scurrying anthill” before returning to his homeland.

It was 1790 when he brought out his first big volume – The General History of Quadrupeds – which covered wild and farm animals.

Before creating his two great volumes on birds, Thomas spent a lot of time visiting collections and having birds sent to him.

Now living in Newcastle, one of his pets was a Corn Crake which fed around his yard like a chicken, and even survived a winter, rather than migrating down to Africa. Corn Crakes would have been very common in those days in the surrounding countryside. He even kept a Reed Bunting, until it moulted into its breeding plumage, just to make sure it was not a different species – it was called a Reed Sparrow in those days!

What’s in a name?

Many of the bird names would have been different, in fact, with localised names around the country to contend with as well. For example, the northern name of Cuckoo was Gowk, from the Scandinavian term for the bird, and several place names incorporating it are still found to this day, especially around Edinburgh and even here in Cumbria.

Of course, for European birders, the name Bewick connects with a swan species first found in the UK in Northumberland. It was found by John Hancock, the son of a good friend of Bewick, and Richard Wingate, who realised it was a new species that had not been named before. As the two of them worshipped Thomas, the bird was later named in his honour by William Yarrell, who gave it the scientific name Cygnus Bewickii in 1830.

This was not the only bird in the world to be named after Thomas. His good friend, John James Audubon, visited him at his works in 1827. Audubon was yet another fan of Thomas’s wood-cuts and marvelled at his skill as one was cut out in front of him. Audubon had found a wren new to science in 1821, and later named the bird after Bewick – Thryomanes bewickii, the Bewick’s Wren.

In fact, Bewick looked set to have another species named after him, but his skills in identifying birds put paid to that. Colonel Montagu (of harrier fame), had seen a bird he called the Red-legged Sandpiper, and wanted to give it the scientific name Tringa Bewickii, but when Thomas saw the skin of the bird, he realised that it was in fact just a plumage variant of the Ruff.

Thomas died in 1828, leaving his son, Robert, to carry on the business. Robert passed away in 1849, ending the life of a workshop which had added so much to the modern birding world. But, while reading an article in a magazine, I spotted some paintings of swans from Ireland. The name on them was Bewick. It couldn’t be, could it?

Family ties

The name Bewick is a common name in Northumberland, due to the fact it comes from an old word for the village (wick) beekeeper.

I sent an email to Poppy, the daughter of Pauline Bewick, whose work I had seen, and sure enough it turned out we were looking at the artwork of one of Thomas Bewick’s relatives.

Pauline was actually born in Northumberland, only a short distance from Cherryburn. Her grandparents were the last Bewicks to live there. Pauline’s mother, Alice, moved away in the 1930s when Pauline was only three, with her sister Hazel, to County Kerry, where she looked after a small farm.

The two girls were encouraged to sleep out under the stars and learn about the countryside. The family moved around Ireland after the farm, but always had a soft spot for Kerry.

Pauline became one of Ireland’s best-known artists and when her two daughters came along, Poppy and Holly, they also became artists. Travelling to both Italy and Polynesia, Pauline showed them parts of the world where art was always part of their life. After settling back in Kerry, Pauline’s work grew in stature and the girls branched out, Poppy staying in Kerry, while Holly moved to Italy.

Trips back to Northumberland were mainly to see relatives, but a quest to find their grandfather’s grave in Ovingham graveyard was a challenge, as it turned out that he was buried without a gravestone. Once the spot of the grave was found, a new gravestone engraved with a Bewick’s Swan seemed the most appropriate.

The family tree is found in the National Trust’s property at Cherryburn today, and along with Thomas’s family, the branches now stretch down to Pauline and her girls and their children.

The evolution of birds in art stretches down from Thomas’s wood-cuts to Pauline and her girls. Who knows, maybe their children will also end up using art to highlight the natural wonders of the world.

More info

For more information please visit: www.bewicksociety.org

The December issue of Bird Watching is available now iun the shops or online by clicking here: https://www.greatmagazines.co.uk/bird-watching-december-2021